Early life

Floyd was a Roman Catholic barrister. He became steward in Shropshire to Lord Chancellor Ellesmere and Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk. [1]

Edward Floyd, Floud or Lloyd (died 1648) was an Englishman impeached and sentenced by the Parliament of England in 1621 for speaking disparagingly of Frederick V, Elector Palatine (by Floyd's Case).

Floyd was a Roman Catholic barrister. He became steward in Shropshire to Lord Chancellor Ellesmere and Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk. [1]

In 1621, when he was in the Fleet Prison at the instance (doing) of the Privy Council, he was impeached by the House of Commons for having said:

I have heard that Prague is taken; and Goodman Palsgrave and Goodwife Palsgrave have taken their heels; and as I have heard, Goodwife Palsgrave is taken prisoner.

These words, it was alleged, he spoke in a scornful manner, to insult the Prince Palatine and his wife Elizabeth of Bohemia, who was daughter to James I of England. The case led to an important constitutional decision on which forums can hold criminal trials with a political dimension and what permission is needed from the Crown and any second House. [1] Shortly before the case, the Commons had looked for precedents supporting their judicial role. They found none save as to contempt for (being in contempt of) the House. During the proceedings they demurred on this lack of precedent. They had to concede the point. [2]

The case came to the House of Commons on 30 April. By then it had been in session since February. It had done nothing on the situation in Bohemia, where the Elector Palatine and his English princess wife had been heavily defeated in a conflict that formed the first phase of the Thirty Years War. [3] On that day the influential parliamentarian Sir Edwin Sandys encouraged the Commons to take punitive action. The feeling of the House was that in this matter they could make their mark in foreign policy, not otherwise in their remit. [4]

The Commons agreed on 1 May that Floyd should pay a fine of £1,000 (equivalent to £200,000in 2019), stand in the pillory at three stands for two hours at each, and be carried from place to place on a horse without a saddle, with his face towards the horse's tail, and holding the tail in his hand. The king, however, objected to the Commons taking up the matter. The next morning he sent (an agent) to inquire upon what precedents the Commons grounded their claim to act as a judicial body in regard to offences which did not concern their privileges. [1] He also pointed out that they had failed to get his approval, and had not granted Floyd due process. Sandys by now had thought better of direct judgement; he argued that as the Speaker had signed nothing, the decision of the Commons was not yet effective. The momentum of the House was against him. Sir Edward Coke pressed for enforcibility, invoking his favoured view of the Commons as court of record. William Noy warned against passing judgement relating to overseas matters. [4]

Two days later the Commons petitioned the king to be allowed their sentence. He argued that it was quite unclear what jurisdiction they were claiming; but agreed to consider the petition and to act in the matter of Floyd. But on 4 May he sent the matter to the House of Lords - poorly timed as (as Sandys had already argued) the upper house was preoccupied with efforts to undermine George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham. [5]

On 5 May the Commons and Lords conferred on the case. Coke worked to salvage the concept of the Commons as court of record, by having the prior record annulled as the lesser of two evils, since the king and Lords appeared set to deny the claim. [6]

A debate of several days then led to a conference of the two houses, when it was agreed that the accused should be arraigned before the Lords, and that a declaration should be entered on the journals that his trial before the commons should not prejudice the just rights of either house. [1]

The Lords added to the severity of the first judgment. On 26 May, Floyd was condemned to be degraded from the estate (state) of a gentleman; his testimony not to be received; he was to be branded, whipped at the cart's tail, fined £5,000, and imprisoned in Newgate Prison for life. When he was branded in Cheapside he declared that he would have given £1,000 to be hanged in order that he might be a martyr in so good a cause. [1]

Some days later, on the motion of Prince Charles, it was agreed by the lords that the whipping should not be inflicted, and an order was made that in future judgment should not be pronounced, when the sentence was more than imprisonment, on the same day on which it was voted. The remainder of the sentence on Floyd seems to have resulted save that he was liberated on 16 July, after the new Lord Chancellor John Williams had prevailed with George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham to recommend to James I an exercise of his prerogative of mercy in the case of political prisoners. [1]

On the petition of Joane, his wife, the Lords on 6 December ordered his trunk and writings to be delivered up to her; the clerk first taking out Catholic books and religious objects. [1]

Henry Hallam criticised the proceedings. [1] Joseph Robson Tanner in 1930 wrote in examining the constitution that the English House of Commons had clearly exceeded their jurisdiction. [7] Charles Howard McIlwain commented that the claim the House made for jurisdiction under parliamentary privilege was "the most extensive and the least justifiable, perhaps, in all parliamentary history; and the far-fetched arguments brought forward in debates in support of the claim are of great interest", citing the record in Thomas Barrington's diary of the parliament. [8]

A collection, made by Sir Harbottle Grimstone, of the proceedings is kept as Harleian MS. 6274, art. 2. [1]

While the House of Lords of the United Kingdom is the upper chamber of Parliament and has government ministers, it for many centuries had a judicial function. It functioned as a court of first instance for the trials of peers, for impeachments, and as a court of last resort in the United Kingdom and prior, the Kingdom of England. Aside from jurisdiction over impeachments the House of Lords functioned as the court of last resort.

Sir Matthew Hale was an influential English barrister, judge and jurist most noted for his treatise Historia Placitorum Coronæ, or The History of the Pleas of the Crown. Born to a barrister and his wife, who had both died by the time he was 5, Hale was raised by his father's relative, a strict Puritan, and inherited his faith. In 1626 he matriculated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, intending to become a priest, but after a series of distractions was persuaded to become a barrister like his father thanks to an encounter with a Serjeant-at-Law in a dispute over his estate. On 8 November 1628 he joined Lincoln's Inn, where he was called to the Bar on 17 May 1636. As a barrister, Hale represented a variety of Royalist figures during the prelude and duration of the English Civil War, including Thomas Wentworth and William Laud; it has been hypothesised that Hale was to represent Charles I at his state trial, and conceived the defence Charles used. Despite the Royalist loss, Hale's reputation for integrity and his political neutrality saved him from any repercussions, and under the Commonwealth of England he was made Chairman of the Hale Commission, which investigated law reform. Following the Commission's dissolution, Oliver Cromwell made him a Justice of the Common Pleas.

Sir Edward Coke was an English barrister, judge, and politician who is considered to be the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

The Petition of Right, passed on 7 June 1628, is an English constitutional document setting out specific individual protections against the state, reportedly of equal value to Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689. It was part of a wider conflict between Parliament and the Stuart monarchy that led to the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, ultimately resolved in the 1688 Glorious Revolution.

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid the slow pace of change and possible harshness of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the estates of lunatics and the guardianship of infants. Its initial role was somewhat different: as an extension of the Lord Chancellor's role as Keeper of the King's Conscience, the Court was an administrative body primarily concerned with conscientious law. Thus the Court of Chancery had a far greater remit than the common law courts, whose decisions it had the jurisdiction to overrule for much of its existence, and was far more flexible. Until the 19th century, the Court of Chancery could apply a far wider range of remedies than common law courts, such as specific performance and injunctions, and had some power to grant damages in special circumstances. With the shift of the Exchequer of Pleas towards a common law court and loss of its equitable jurisdiction by the Administration of Justice Act 1841, the Chancery became the only national equitable body in the English legal system.

Thomas Coventry, 1st Baron Coventry was a prominent English lawyer, politician and judge during the early 17th century.

Thomas Morton was an English churchman, bishop of several dioceses. Well-connected and in favour with James I, he was also a significant polemical writer against Roman Catholic views. He rose to become Bishop of Durham, but despite a record of sympathetic treatment of Puritans as a diocesan, and underlying Calvinist beliefs shown in the Gagg controversy, his royalism saw him descend into poverty under the Commonwealth.

In the United Kingdom, a Member of Parliament (MP) is an individual elected to serve in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester was an English art collector, diplomat and Secretary of State.

Hindon was a parliamentary borough consisting of the village of Hindon in Wiltshire, which elected two Members of Parliament (MPs) to the House of Commons from 1448 until 1832, when the borough was abolished by the Great Reform Act. It was one of the most notoriously corrupt of the rotten boroughs, and bills to disfranchise Hindon were debated in Parliament on two occasions before its eventual abolition.

Sir RanulphCrewe was an English judge and Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Ashby v White (1703) 92 ER 126, is a foundational case in UK constitutional law and English tort law. It concerns the right to vote and misfeasance of a public officer.

The World Tossed at Tennis is a Jacobean era masque composed by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley, first published in 1620. It was likely acted on 4 March 1620 at Denmark House.

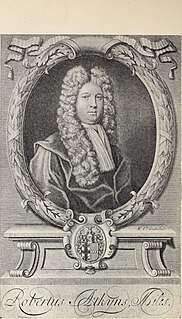

Sir Robert Atkyns KCB KS (1620–1710) was an English Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer, Member of parliament, and Speaker of the House of Lords.

Sir Samuel Barnardiston, 1st Baronet (1620–1707) was an English Whig Member of Parliament and deputy governor of the East India Company, defendant in some high-profile legal cases and involved in a highly contentious parliamentary election.

Edward Alford was an English landowner and politician who sat in seven parliaments in the House of Commons between 1604 and 1628.

Sir Robert Phelips was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1604 and 1629. In his later Parliaments he was one of the leading spirits in the House of Commons and an opponent of James I, Charles I and their adviser Buckingham.

Sir Nicholas Fuller was an English barrister and Member of Parliament. After studying at Christ's College, Cambridge, Fuller became a barrister of Gray's Inn. His legal career there began prosperously—he was employed by the Privy Council to examine witnesses—but was hampered later by his representation of the Puritans, a religious tendency which did not conform with the established Church of England. Fuller was repeatedly in contention with the ecclesiastical courts, including the Star Chamber and Court of High Commission, and was once expelled for the zeal with which he defended his client. In 1593 he was returned as the Member of Parliament for St Mawes, where he campaigned against the extension of recusancy laws. Outside of Parliament, he successfully brought a patents case which not only undermined the right of the Crown to issue patents but accurately predicted the attitude taken by the Statute of Monopolies two decades later.

Calvin's CaseCalvin's Case (1608), 77 ER 377 also known as the Case of the Postnati, was a 1608 English legal decision establishing that a child born in Scotland, after the Union of the Crowns under James VI and I in 1603, was considered under the common law to be an English subject and entitled to the benefits of English law. Calvin's Case was eventually adopted by courts in the United States, and the case played an important role in shaping the American rule of birthright citizenship via jus soli. However, the case has also been cited as providing legal justification for the restriction of legal rights to Native Americans following their widespread conquest or confinement in reservations by the colonial forces of North America.

Thomas Yonge or Young was an English judge.

![]()