In linguistics, syntax is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency), agreement, the nature of crosslinguistic variation, and the relationship between form and meaning (semantics). There are numerous approaches to syntax that differ in their central assumptions and goals.

In grammar, a phrase—called expression in some contexts—is a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adjective phrase "very happy". Phrases can consist of a single word or a complete sentence. In theoretical linguistics, phrases are often analyzed as units of syntactic structure such as a constituent. There is a difference between the common use of the term phrase and its technical use in linguistics. In common usage, a phrase is usually a group of words with some special idiomatic meaning or other significance, such as "all rights reserved", "economical with the truth", "kick the bucket", and the like. It may be a euphemism, a saying or proverb, a fixed expression, a figure of speech, etc.. In linguistics, these are known as phrasemes.

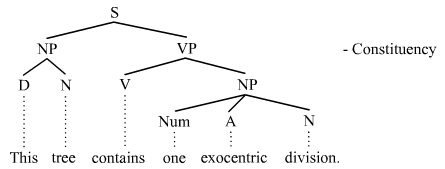

Phrase structure rules are a type of rewrite rule used to describe a given language's syntax and are closely associated with the early stages of transformational grammar, proposed by Noam Chomsky in 1957. They are used to break down a natural language sentence into its constituent parts, also known as syntactic categories, including both lexical categories and phrasal categories. A grammar that uses phrase structure rules is a type of phrase structure grammar. Phrase structure rules as they are commonly employed operate according to the constituency relation, and a grammar that employs phrase structure rules is therefore a constituency grammar; as such, it stands in contrast to dependency grammars, which are based on the dependency relation.

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently occurring phrase type.

A parse tree or parsing tree is an ordered, rooted tree that represents the syntactic structure of a string according to some context-free grammar. The term parse tree itself is used primarily in computational linguistics; in theoretical syntax, the term syntax tree is more common.

Lexical semantics, as a subfield of linguistic semantics, is the study of word meanings. It includes the study of how words structure their meaning, how they act in grammar and compositionality, and the relationships between the distinct senses and uses of a word.

In linguistics, X-bar theory is a model of phrase-structure grammar and a theory of syntactic category formation that was first proposed by Noam Chomsky in 1970 reformulating the ideas of Zellig Harris (1951), and further developed by Ray Jackendoff, along the lines of the theory of generative grammar put forth in the 1950s by Chomsky. It attempts to capture the structure of phrasal categories with a single uniform structure called the X-bar schema, basing itself on the assumption that any phrase in natural language is an XP that is headed by a given syntactic category X. It played a significant role in resolving issues that phrase structure rules had, representative of which is the proliferation of grammatical rules, which is against the thesis of generative grammar.

In linguistics, a verb phrase (VP) is a syntactic unit composed of a verb and its arguments except the subject of an independent clause or coordinate clause. Thus, in the sentence A fat man quickly put the money into the box, the words quickly put the money into the box constitute a verb phrase; it consists of the verb put and its arguments, but not the subject a fat man. A verb phrase is similar to what is considered a predicate in traditional grammars.

In linguistics, the head or nucleus of a phrase is the word that determines the syntactic category of that phrase. For example, the head of the noun phrase boiling hot water is the noun water. Analogously, the head of a compound is the stem that determines the semantic category of that compound. For example, the head of the compound noun handbag is bag, since a handbag is a bag, not a hand. The other elements of the phrase or compound modify the head, and are therefore the head's dependents. Headed phrases and compounds are called endocentric, whereas exocentric ("headless") phrases and compounds lack a clear head. Heads are crucial to establishing the direction of branching. Head-initial phrases are right-branching, head-final phrases are left-branching, and head-medial phrases combine left- and right-branching.

In linguistics, branching refers to the shape of the parse trees that represent the structure of sentences. Assuming that the language is being written or transcribed from left to right, parse trees that grow down and to the right are right-branching, and parse trees that grow down and to the left are left-branching. The direction of branching reflects the position of heads in phrases, and in this regard, right-branching structures are head-initial, whereas left-branching structures are head-final. English has both right-branching (head-initial) and left-branching (head-final) structures, although it is more right-branching than left-branching. Some languages such as Japanese and Turkish are almost fully left-branching (head-final). Some languages are mostly right-branching (head-initial).

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesnière. Dependency is the notion that linguistic units, e.g. words, are connected to each other by directed links. The (finite) verb is taken to be the structural center of clause structure. All other syntactic units (words) are either directly or indirectly connected to the verb in terms of the directed links, which are called dependencies. Dependency grammar differs from phrase structure grammar in that while it can identify phrases it tends to overlook phrasal nodes. A dependency structure is determined by the relation between a word and its dependents. Dependency structures are flatter than phrase structures in part because they lack a finite verb phrase constituent, and they are thus well suited for the analysis of languages with free word order, such as Czech or Warlpiri.

The term phrase structure grammar was originally introduced by Noam Chomsky as the term for grammar studied previously by Emil Post and Axel Thue. Some authors, however, reserve the term for more restricted grammars in the Chomsky hierarchy: context-sensitive grammars or context-free grammars. In a broader sense, phrase structure grammars are also known as constituency grammars. The defining character of phrase structure grammars is thus their adherence to the constituency relation, as opposed to the dependency relation of dependency grammars.

In generative grammar, non-configurational languages are languages characterized by a flat phrase structure, which allows syntactically discontinuous expressions, and a relatively free word order.

The term predicate is used in two ways in linguistics and its subfields. The first defines a predicate as everything in a standard declarative sentence except the subject, and the other defines it as only the main content verb or associated predicative expression of a clause. Thus, by the first definition, the predicate of the sentence Frank likes cake is likes cake, while by the second definition, it is only the content verb likes, and Frank and cake are the arguments of this predicate. The conflict between these two definitions can lead to confusion.

Topicalization is a mechanism of syntax that establishes an expression as the sentence or clause topic by having it appear at the front of the sentence or clause. This involves a phrasal movement of determiners, prepositions, and verbs to sentence-initial position. Topicalization often results in a discontinuity and is thus one of a number of established discontinuity types, the other three being wh-fronting, scrambling, and extraposition. Topicalization is also used as a constituency test; an expression that can be topicalized is deemed a constituent. The topicalization of arguments in English is rare, whereas circumstantial adjuncts are often topicalized. Most languages allow topicalization, and in some languages, topicalization occurs much more frequently and/or in a much less marked manner than in English. Topicalization in English has also received attention in the pragmatics literature.

In linguistics, grammatical relations are functional relationships between constituents in a clause. The standard examples of grammatical functions from traditional grammar are subject, direct object, and indirect object. In recent times, the syntactic functions, typified by the traditional categories of subject and object, have assumed an important role in linguistic theorizing, within a variety of approaches ranging from generative grammar to functional and cognitive theories. Many modern theories of grammar are likely to acknowledge numerous further types of grammatical relations.

In linguistics, antisymmetry is a syntactic theory presented in Richard S. Kayne's 1994 monograph The Antisymmetry of Syntax. It asserts that grammatical hierarchies in natural language follow a universal order, namely specifier-head-complement branching order. The theory builds on the foundation of the X-bar theory. Kayne hypothesizes that all phrases whose surface order is not specifier-head-complement have undergone syntactic movements that disrupt this underlying order. Others have posited specifier-complement-head as the basic word order.

In linguistics, coordination is a complex syntactic structure that links together two or more elements; these elements are called conjuncts or conjoins. The presence of coordination is often signaled by the appearance of a coordinator, e.g. and, or, but. The totality of coordinator(s) and conjuncts forming an instance of coordination is called a coordinate structure. The unique properties of coordinate structures have motivated theoretical syntax to draw a broad distinction between coordination and subordination. It is also one of the many constituency tests in linguistics. Coordination is one of the most studied fields in theoretical syntax, but despite decades of intensive examination, theoretical accounts differ significantly and there is no consensus on the best analysis.

In linguistics, subordination is a principle of the hierarchical organization of linguistic units. While the principle is applicable in semantics, morphology, and phonology, most work in linguistics employs the term "subordination" in the context of syntax, and that is the context in which it is considered here. The syntactic units of sentences are often either subordinate or coordinate to each other. Hence an understanding of subordination is promoted by an understanding of coordination, and vice versa.

Merge is one of the basic operations in the Minimalist Program, a leading approach to generative syntax, when two syntactic objects are combined to form a new syntactic unit. Merge also has the property of recursion in that it may be applied to its own output: the objects combined by Merge are either lexical items or sets that were themselves formed by Merge. This recursive property of Merge has been claimed to be a fundamental characteristic that distinguishes language from other cognitive faculties. As Noam Chomsky (1999) puts it, Merge is "an indispensable operation of a recursive system ... which takes two syntactic objects A and B and forms the new object G={A,B}" (p. 2).