Related Research Articles

Nikolai Nikolayevich Luzin was a Soviet and Russian mathematician known for his work in descriptive set theory and aspects of mathematical analysis with strong connections to point-set topology. He was the eponym of Luzitania, a loose group of young Moscow mathematicians of the first half of the 1920s. They adopted his set-theoretic orientation, and went on to apply it in other areas of mathematics.

Abram Moiseyevich Deborin (Ioffe) was a Soviet Marxist philosopher and academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union (1929). Deborin oscillated between The Bolshevik and Menshevik factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, before settling with the Bolsheviks and enjoying a long career as a philosopher in the Soviet Union. Although this career suffered under Stalin, he lived to see his works republished when the Soviet Union was led by Nikita Khrushchev.

Philosophy in the Soviet Union was officially confined to Marxist–Leninist thinking, which theoretically was the basis of objective and ultimate philosophical truth. During the 1920s and 1930s, other tendencies of Russian thought were repressed. Joseph Stalin enacted a decree in 1931 identifying dialectical materialism with Marxism–Leninism, making it the official philosophy which would be enforced in all communist states and, through the Comintern, in most communist parties. Following the traditional use in the Second International, opponents would be labeled as "revisionists".

Vladimir Viktorovich Adoratsky was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet historian, academic and Marxist philosopher.

Fundamentals of Marxism–Leninism is a book by a group of Soviet authors headed by Otto Wille Kuusinen. The work is considered one of the fundamental works on dialectical materialism and on Leninist communism. The book remains important in understanding the philosophy and politics of the Soviet Union; it consolidates the work of important contributions to Marxist theory.

Dialectical and Historical Materialism, by Joseph Stalin, is a central text within the Soviet Union's political theory Marxism–Leninism.

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic, economic, social and political change. It frames capitalism through a paradigm of exploitation and analyzes class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development – materialist in the sense that the politics and ideas of an epoch are determined by the way in which material production is carried on.

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov was a Russian revolutionary, philosopher and Marxist theorist. Known as the "father of Russian Marxism", Plekhanov was a highly influential figure among Russian radicals, including Vladimir Lenin.

Marxist–Leninist atheism, also known as Marxist–Leninist scientific atheism, is the antireligious element of Marxism–Leninism. Based upon a dialectical-materialist understanding of humanity's place in nature, Marxist–Leninist atheism proposes that religion is the opium of the people; thus, Marxism–Leninism advocates atheism, rather than religious belief.

Marxist historiography, or historical materialist historiography, is an influential school of historiography. The chief tenets of Marxist historiography include the centrality of social class, social relations of production in class-divided societies that struggle against each other, and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. Marxist historians follow the tenets of the development of class-divided societies, especially modern capitalist ones.

György Lukács was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an interpretive tradition that departed from the Soviet Marxist ideological orthodoxy. He developed the theory of reification, and contributed to Marxist theory with developments of Karl Marx's theory of class consciousness. He was also a philosopher of Leninism. He ideologically developed and organised Lenin's pragmatic revolutionary practices into the formal philosophy of vanguard-party revolution.

Mark Borisovich Mitin was a Soviet Marxist–Leninist philosopher, university lecturer and Professor of Philosophy Faculty of Moscow State University. He was interested primarily dialectical and historical materialism, the philosophy of history and criticism of bourgeois philosophy.

Dialectical materialism is a materialist theory based upon the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that has found widespread applications in a variety of philosophical disciplines ranging from philosophy of history to philosophy of science. As a materialist philosophy, Marxist dialectics emphasizes the importance of real-world conditions and the presence of functional contradictions within and among social relations, which derive from, but are not limited to, the contradictions that occur in social class, labour economics, and socioeconomic interactions. Within Marxism, a contradiction is a relationship in which two forces oppose each other, leading to mutual development.

The Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute, established in Moscow in 1919 as the Marx–Engels Institute, was a Soviet library and archive attached to the Communist Academy. The institute was later attached to the governing Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and served as a research center and publishing house for officially published works of Marxist thought. From 1956 to 1991, the institute was named the Institute of Marxism–Leninism.

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Marxism:

Ivan Kapitonovich Luppol was a Soviet philosopher, literary critic and academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union.

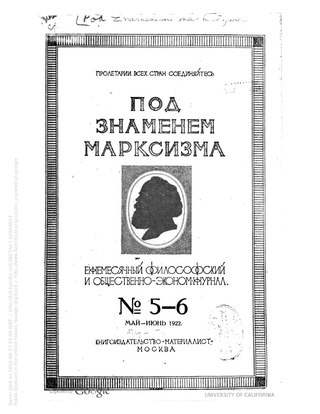

Under the Banner of Marxism was a Soviet philosophical and socio-economic journal published in Moscow from 1922 to 1944. It was published monthly, except for 1933–1935, when it was published bi-monthly.

The Second International Congress of the History of Science was held in London from June 29 to July 4, 1931. The Congress was organised by the International Committee of History of Science, in conjunction with the Comité International des Sciences Historiques. The History of Science Society and the Newcomen Society also supported the event. Charles Singer presided over the congress. Although organised by the International Committee of History of Science, it was during this congress that this organisation was transformed into an individual membership organisation called the International Academy of the History of Science.

Pyotr Nikolaevich Fedoseyev was a Soviet philosopher, sociologist, politician and public figure.

References

- 1 2 "Prof. Ernst Kolman, A Confidant of Lenin, Dies in Sweden at 85". The New York Times . 26 January 1979.

(Reuters) Prof. Ernst Kolman, confidant of Lenin and pupil of Einstein, has died in a Stockholm suburb at the age of 85.

- ↑ Taubman, William (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era . W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05144-7.

- ↑ Marx’s brilliant study of mathematics

- ↑ Levin, A. E. (1990). "Anatomy of a public campaign: "Academician Luzin's case" in Soviet political history". Slavic Review. 49 (1). Slavic Review, Vol. 49, No. 1: 90–108. doi:10.2307/2500418. JSTOR 2500418. S2CID 155570928.

- ↑ IDEOLOGIES: The Consolations of Philosophy

- ↑ Krasnov, Vladislav (1986). Soviet Defectors: The KGB Wanted List. Stanford: Hoover Institution, Stanford University.