Related Research Articles

Achy Obejas is a Cuban-American writer and translator focused on personal and national identity issues, living in Benicia, California. She frequently writes on her sexuality and nationality, and has received numerous awards for her creative work. Obejas' stories and poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, Fifth Wednesday Journal, TriQuarterly, Another Chicago Magazine and many other publications. Some of her work was originally published in Esto no tiene nombre, a Latina lesbian magazine published and edited by tatiana de la tierra, which gave voice to the Latina lesbian community. Obejas worked as a journalist in Chicago for more than two decades. For several years, she was also a writer in residence at the University of Chicago, University of Hawaii, DePaul University, Wichita State University, and Mills College in Oakland, California. She also worked from 2019 to 2022 as a writer/editor for Netflix on the bilingual team in the Product Writing department.

Cherríe Moraga is a Xicana feminist, writer, activist, poet, essayist, and playwright. She is part of the faculty at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of English since 2017, and in 2022 became a distinguished professor. Moraga is also a founding member of the social justice activist group La Red Xicana Indígena, which is network fighting for education, culture rights, and Indigenous Rights. In 2017, she co-founded, with Celia Herrera Rodríguez, Las Maestras Center for Xicana Indigenous Thought, Art, and Social Practice, located on the campus of UC Santa Barbara.

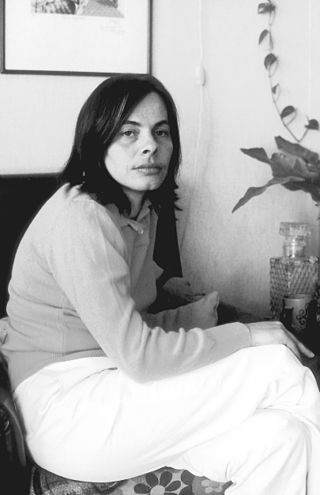

Cristina Peri Rossi is a Uruguayan novelist, poet, translator, and author of short stories.

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press was an activist feminist press that was closely related to the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) which was started in 1980 following a phone conversation between Barbara Smith and at the suggestion of her friend, poet Audre Lorde. Beverly and Barbara Smith and their associate Demita Frazier together cofounded the Combahee River Collective (CRC). The Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press was most active beginning in 1981, but the Press became inactive soon after Audre Lorde's death in 1992. Smith explains how the motivation for starting a press run by and for women of color was that "as feminist and lesbian of color writers, we knew that we had no options for getting published, except at the mercy or whim of others, whether in the context of alternative or commercial publishing, since both are white-dominated."

Alexander John Goodrum (1960–2002) was an African-American transgender civil rights activist, writer, and educator. He was the founder and director of TGNet Arizona. He was a board member of the Tucson GLBT Commission, and the Funding Exchange's OUT Fund, which allocates an annual grant named after Goodrum to LGBT community organizing projects such as the Latina lesbian magazine Esto no tiene nombre, edited in part by tatiana de la tierra.

Carmen Vázquez was an American activist, writer, and community intellectual.

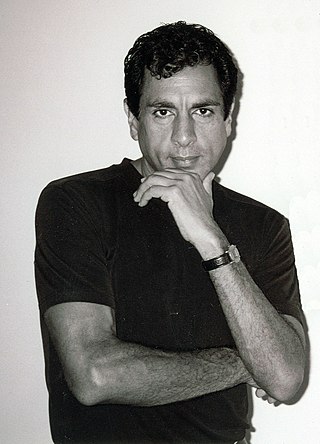

Benito Pastoriza Iyodo was an author of poetry, poetics, fiction, and literary articles. The themes of his literary works included man's evolution from childhood to adulthood, examination of self, the precipices of culture and its rituals, violence in the cities, examination of stereotypes, the constructs of communication, gender roles and sexuality, education systems and racism, exploitation and the manifestation of exclusion through political and economic powers.

Luz María "Luzma" Umpierre-Herrera is a Puerto Rican advocate for human rights, a New-Humanist educator, poet, and scholar. Her works pans a range of critical social issues, including activism and social equality, the immigrant experience, bilingualism in the United States, and LGBT matters. Luzma has made significant contributions to literature, authoring six poetry collections and two books on literary criticism, in addition to having many essays featured in academic journals.

Alina Troyano, more commonly known as Carmelita Tropicana, is a Cuban-American stage and film lesbian actress who lives and works in New York City.

Racism is a concern for many in the Western lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) communities, with members of racial, ethnic, and national minorities reporting having faced discrimination from other LGBT people.

Mama Cash is the oldest international women's fund in the world, founded in the Netherlands in 1983. In 2013, Mama Cash supported 118 women's, girls and trans rights organisations with 4.3 million euros.

The Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice is an international charitable foundation based in the United States focused on issues related to LGBT and intersex rights for people of color. The organization provide grants to individuals and organizations, promotes philanthropy, and provides capacity building assistance.

Tatiana de la tierra was a Colombian writer, poet and activist. She was the author of the first international Latina lesbian magazine Esto no tiene nombre.

Esto no tiene nombre may refer to:

LGBT in Argentina refers to the diversity of practices, militancies and cultural assessments on sexual diversity that were historically deployed in the territory that is currently the Argentine Republic. It is particularly difficult to find information on the incidence of homosexuality in societies from Hispanic America as a result of the anti-homosexual taboo derived from Christian morality, so most of the historical sources of its existence are found in acts of repression and punishment. One of the main conflicts encountered by LGBT history researchers is the use of modern concepts that were non-existent to people from the past, such as "homosexual", "transgender" and "travesti", falling into an anachronism. Non-heterosexuality was historically characterized as a public enemy: when power was exercised by the Catholic Church, it was regarded as a sin; during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when it was in the hands of positivist thought, it was viewed as a disease; and later, with the advent of civil society, it became a crime.

Lesbians during the socialist government of Felipe González experienced several legal and cultural developments that resulted in more rights and community awareness.

Lesbians in the Spanish democratic transition period experienced an increase in civil rights compared to Francoist rule, including the 1978 repeal of a national law criminalizing homosexuality. Following the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, the societal attitude towards homosexuals was repressive. The transition brought forth changes but it was a slow process. Homosexuality was illegal under Franco's regime. During the transition, there was an initial sense of liberalization and greater freedom of expression. Societal attitudes towards homosexuality were ignored in the beginning portion of the transition, but there was no recognition of same-sex relations when it came to legal terms. It was not until the late 20th and 21st century that Spain saw significant progress in LGBTQ+ rights. Legal reforms and social movements gradually led to decriminalization of homosexuality, and later the recognition of same-sex marriage.

Valeria Flores, also stylized as val flores, is an Argentinian writer, teacher and lesbian queer activist. She is dedicated to queer theory and pro-sex feminism. She writes theoretical essays characterized by a poetic writing, and poetry. Along her published books we find: interruqciones. Ensayos de poética activista, Deslenguada. Desbordes de una proletaria del lenguaje y El sótano de San Telmo. Una barricada proletaria para el deseo lésbico en los 70. She also carries out performances and workshops as forms of political, aesthetic and pedagogical intervention.

References

- ↑ de la tierra, tatiana (2010). "Inside the files of "This Has No Name"". In Greenblatt, Ellen (ed.). Serving LGBTIQ Library and Archives Users: Essays on Outreach, Service, Collections and Access. pp. 162–164. ISBN 9780786461844 . Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Latina lesbian literature". Encyclopedia of Hispanic-American Literature. Infobase learning. 2015. ISBN 9781438140605.

- ↑ de la tierra, tatiana (2010). "Latina Lesbians in Motion". In Vida, Ginny (ed.). New Our Right to Love: a Lesbian Resource Book. Simon & Schuster. p. 227. ISBN 9781439145418.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 de la tierra, tatiana (1 November 2001). "Activist Latina Lesbian Publishing: Esto no tiene nombre y conmocion".

- 1 2 Costa, María Dolores. "Latina Lesbian Writers and Performers: An Overview." Journal of lesbian studies 7.3 (2003): 5-27.

- 1 2 Rodríguez, Juana María. “Activism and Identity in the Ruins of Representation.” Queer Latinidad: Identity practices, discursive spaces. NYU Press, 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Torres, Lourdes. "Becoming Visible: US Latina Lesbians Talk Back and Act Out." Counterpoints 169 (2002): 151-162.

- 1 2 3 de la tierra, tatiana. “Latina Lesbian Literary Herstory: From Sor Juana to Days of Awe.” The Power of Language/El poder de la palabra: Selected Papers from the Second REFORMA National Conference. Ed. Lillian Castillo-Speed and the REFORMA National Conference Publications Committee. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited. 2001: 199-212. http://delatierra.net/?page_id=1029

- 1 2 3 de Alba, Alicia Gaspar. “"tortillerismo": Work by Chicana Lesbians”. Signs 18.4 (1993): 956–963.

- 1 2 3 de la tierra, tatiana. “The L Word(s) Among Us in the Library World.” GLBTRT NewsletterSpring 2004: 4-5.

- 1 2 3 Acosta, Katie L.. “LESBIANAS IN THE BORDERLANDS: Shifting Identities and Imagined Communities”. Gender and Society 22.5 (2008): 639–659.