Evidence

In July 2003, at a conference in California, it was announced that the Gamma Ray Spectrometer (GRS) on board the Mars Odyssey had discovered huge amounts of water over vast areas of Mars. Mars has enough ice just beneath the surface to fill Lake Michigan twice. [1] In both hemispheres, from 55 degrees latitude to the poles, Mars has a high density of ice just under the surface; one kilogram of soil contains about 500 g of water ice. But, close to the equator, there is only 2 to 10% of water in the soil. [2] [3] Scientists believe that much of this water is locked up in the chemical structure of minerals, such as clay and sulfates. Previous studies with infrared spectroscopes have provided evidence of small amounts of chemically or physically bound water. [4] [5]

The Viking landers detected low levels of chemically bound water in the Martian soil. [6] It is believed that although the upper surface only contains a percent or so of water, ice may lie just a few feet deeper. Some areas, Arabia Terra, Amazonis quadrangle, and Elysium quadrangle contain large amounts of water. [2] [7] Analysis of the data suggest that the southern hemisphere may have a layered structure. [8] Both of the poles showed buried ice, but the north pole had none close to it because it was covered over by seasonal carbon dioxide (dry ice). When the measurements were gathered, it was winter at the north pole so carbon dioxide had frozen on top of the water ice. [1] There may be much more water further below the surface; the instruments aboard the Mars Odyssey are only able to study the top meter or so of soil. If all holes in the soil were filled by water, this would correspond to a global layer of water 0.5 to 1.5 km deep. [9]

The Phoenix lander confirmed the initial findings of the Mars Odyssey. [10] It found ice a few inches below the surface and the ice is at least 8 inches deep. When the ice is exposed to the Martian atmosphere it slowly sublimates. In fact, some of the ice was exposed by the landing rockets of the craft. [11]

Thousands of images returned from Odyssey support the idea that Mars once had great amounts of water flowing across its surface. Some pictures show patterns of branching valleys. Others show layers that may have formed under lakes. Deltas have been identified. [12] For many years researchers believed that glaciers existed under a layer of insulating rocks. [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] Lineated valley fill is one example of these rock-covered glaciers. They are found on the floors of some channels. Their surfaces have ridged and grooved materials that deflect around obstacles. Some glaciers on the Earth show such features. Lineated floor deposits may be related to Lobate debris aprons, which have been proven to contain large amounts of ice by orbiting radar. [16] [17] [18]

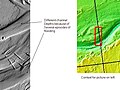

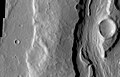

The pictures below, taken with the THEMIS instrument on board the Mars Odyssey, show examples of features that are associated with water present in the present or past. [19]

- Drainage features in Reull Vallis. Click on image to see relationship of Reull Vallis to other features. Location is Hellas quadrangle.

- Reull Vallis with lineated floor deposits. Click on image to see relationship to other features. Floor deposits are believed to be formed from ice movement. Location is Hellas quadrangle.

- Auqakuh Vallis. At one time a dark layer covered the whole area, now only a few pieces remain as buttes. Click on image to see layers. Layers may have formed from deposition on the bottom of lakes.

- Huo Hsing Vallis in Syrtis Major quadrangle. Straight ridges may be dikes in which liquid rock once flowed.

- Nirgal Vallis that runs in two quadrangles has features looking like those caused by sapping. Nirgal Vallis is one of many ancient river valleys studied by THEMIS.

- The long channel Nirgal Vallis is shown where it connects to Uzboi Vallis. The crater Luki is 21 km in diameter.

- Nirgal Vallis.

- Nirgal Vallis Close-up.

- Channels near Warrego Valles. These branched channels are strong evidence for flowing water on Mars, perhaps during a much warmer period.

- Semeykin Crater Drainage. Click on image to see details of beautiful drainage system. Location is Ismenius Lacus quadrangle.

- Erosion features in Ares Vallis – the streamlined shape was probably formed by running water.

- Delta in Lunae Palus quadrangle.

- Delta in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle.

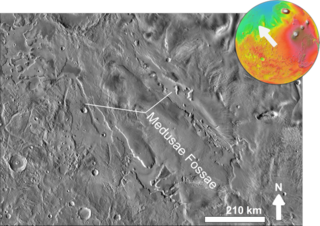

- Athabasca Valles showing source of its water, Cerberus Fossae. Note streamlined islands which show direction of flow to south. Athabasca Valles is in the Elysium quadrangle.

- Close-up of Padus Vallis. Padus Vallis is in the Memnonia quadrangle.

- Channels West of Echus Chasma. The fine pattern of branching valleys were probably formed by water moving across the surface. Image is in Coprates quadrangle.

- Dendritic channels on mesa of Echus Chasma. Image is 20 miles wide. Image is in Coprates quadrangle.

- Branching channels on floor of Melas Chasma. Image is in Coprates quadrangle.

Dao Vallis begins near a large volcano, called Hadriaca Patera, so it is thought to have received water when hot magma melted huge amounts of ice in the frozen ground. The partially circular depressions on the left side of the channel in the image above suggests that groundwater sapping also contributed water. [20] In some areas large river valleys begin with a landscape feature called "Chaos" or Chaotic Terrain." It is thought that the ground collapsed, as huge amounts of water were suddenly released. Examples of Chaotic terrain, as imaged by THEMIS, are shown below.

- Blocks in Aram showing possible source of water. The ground collapsed when large amounts of water were released. The large blocks probably still contain some water ice. Location is Oxia Palus quadrangle.

- Huge canyons in Aureum Chaos. Click on image to see the gullies which may have formed from recent flows of water. Gullies are rare at this latitude. Location is Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle.