Related Research Articles

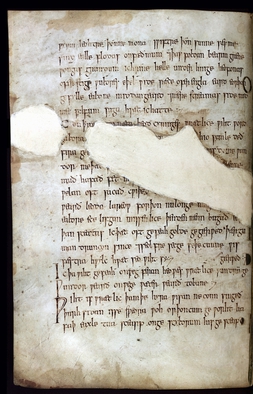

Christ III is an anonymous Old English religious poem which forms the last part of Christ, a poetic triad found at the beginning of the Exeter Book. Christ III is found on fols. 20b–32a and constitutes lines 867–1664 of Christ in Krapp and Dobbie's Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records edition. The poem is concerned with the Second Coming of Christ (parousia) and the Last Judgment.

Exeter Book Riddle 83 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its interpretation has occasioned a range of scholarly investigations, but it is taken to mean 'Ore/Gold/Metal', with most commentators preferring 'precious metal' or 'gold', and John D. Niles arguing specifically for the Old English solution ōra, meaning both 'ore' and 'a kind of silver coin'.

The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records (ASPR) is a six-volume edition intended at the time of its publication to encompass all known Old English poetry. Despite many subsequent editions of individual poems or collections, it has remained the standard reference work for scholarship in this field.

Exeter Book Riddles 68 and 69 are two of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Their interpretation has occasioned a range of scholarly investigations, but clearly has something to do with ice and one or both of the riddles are likely indeed to have the solution "ice".

Exeter Book Riddle 60 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is usually solved as 'reed pen', although such pens were not in use in Anglo-Saxon times, rather being Roman technology; but it can also be understood as 'reed pipe'.

Exeter Book Riddle 27 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is almost universally solved as 'mead'.

Exeter Book Riddle 47 is one of the most famous of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is 'book-worm' or 'moth'.

De creatura is an 83-line Latin polystichic poem by the seventh- to eighth-century Anglo-Saxon poet Aldhelm and an important text among Anglo-Saxon riddles. The poem seeks to express the wondrous diversity of creation, usually by drawing vivid contrasts between different natural phenomena, one of which is usually physically higher and more magnificent, and one of which is usually physically lower and more mundane.

The Exeter Book riddles are a fragmentary collection of verse riddles in Old English found in the later tenth-century anthology of Old English poetry known as the Exeter Book. Today standing at around ninety-four, the Exeter Book riddles account for almost all the riddles attested in Old English, and a major component of the otherwise mostly Latin corpus of riddles from early medieval England.

Exeter Book Riddle 30 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Since the suggestion of F. A. Blackburn in 1901, its solution has been agreed to be the Old English word bēam, understood both in its primary sense 'tree' but also in its secondary sense 'cross'.

Exeter Book Riddle 24 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is one of a number to include runes as clues: they spell an anagram of the Old English word higoræ 'jay, magpie'. There has, therefore, been little debate about the solution.

Exeter Book Riddle 45 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'dough'. However, the description evokes a penis becoming erect; as such, Riddle 45 is noted as one of a small group of Old English riddles that engage in sexual double entendre, and thus provides rare evidence for Anglo-Saxon attitudes to sexuality, and specifically for women taking the initiative in heterosexual sex.

Exeter Book Riddle 44 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'key'. However, the description evokes a penis; as such, Riddle 44 is noted as one of a small group of Old English riddles that engage in sexual double entendre, and thus provides rare evidence for Anglo-Saxon attitudes to sexuality.

Exeter Book Riddle 25 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Suggested solutions have included Hemp, Leek, Onion, Rosehip, Mustard and Phallus, but the consensus is that the solution is Onion.

Exeter Book Riddle 33 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'Iceberg'. The most extensive commentary on the riddle is by Corinne Dale, whose ecofeminist analysis of the riddles discusses how the iceberg is portrayed through metaphors of warrior violence but at the same time femininity.

Exeter Book Riddle 12 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'ox/ox-hide'. The riddle has been described as 'rather a cause celebre in the realm of Old English poetic scholarship, thanks to the combination of its apparently sensational, and salacious, subject matter with critical issues of class, sex, and gender'. The riddle is also of interest because of its reference to an enslaved person, possibly ethnically British.

Exeter Book Riddle 61 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is usually solved as 'shirt', 'mailcoat' or 'helmet'. It is noted as one of a number of Old English riddles with sexual connotations and as a source for gender-relations in early medieval England.

Exeter Book Riddle 7 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book, in this case on folio 103r. The solution is believed to be 'swan' and the riddle is noted as being one of the Old English riddles whose solution is most widely agreed on. The riddle can be understood in its manuscript context as part of a sequence of bird-riddles.

Exeter Book Riddle 26 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book.

Exeter Book Riddle 9 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book, in this case on folio 103r–v. The solution is believed to be 'cuckoo'. The riddle can be understood in its manuscript context as part of a sequence of bird-riddles.

References

- 1 2 George Philip Krapp and Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie (eds), The Exeter Book, The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records, 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), http://ota.ox.ac.uk/desc/3009 Archived 2018-12-06 at the Wayback Machine .

- 1 2 Judy Kendall, 'Commentary for Riddle 65', The Riddle Ages (17 August 2017).

- ↑ Andrew Higl, 'Riddle Hero: Play and Poetry in the Exeter Book Riddles', American Journal of Play, 9 (2017), 374-94 (p. 389).

- ↑ Symphosius, The 'Aenigmata': An Introduction, Text, and Commentary, ed. and trans. by T. J. Leary (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), p. 142 (no. 44).