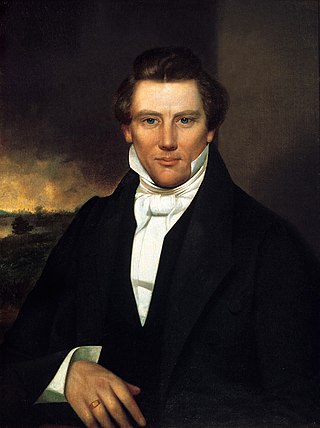

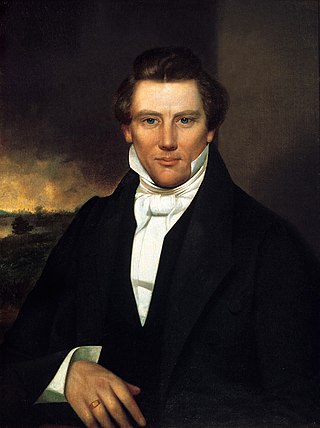

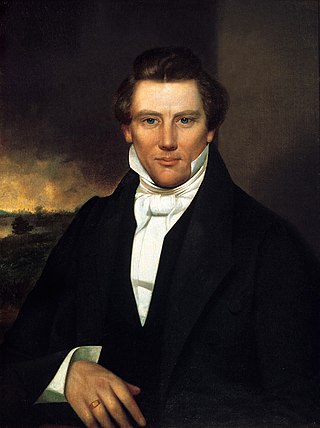

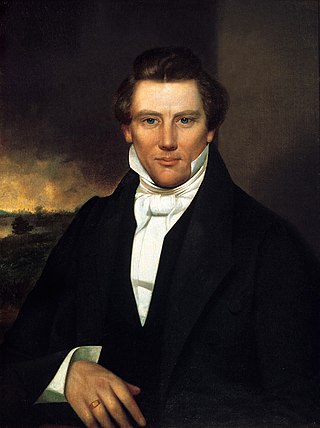

The Danites were a fraternal organization founded by Latter Day Saint members in June 1838, in the town of Far West, Caldwell County, Missouri. During their period of organization in Missouri, the Danites operated as a vigilante group and took a central role in the events of the 1838 Mormon War. They remained an important part of Mormon and non-Mormon folklore, polemics, and propaganda for the remainder of the 19th century, waning in ideological prominence after Utah gained statehood. Notwithstanding public excommunications of Danite leaders by the Church and both public and private statements from Joseph Smith referring to the band as being both evil in nature and a "secret combination", the nature and scope of the organization and the degree to which it was officially connected to the Church of Christ are not agreed between historians. Early in the group's existence, Joseph Smith appeared to endorse its actions, but later turned against it as violence increased and the actions of the Danites inspired a hysteria in Missouri that eventually led to the Extermination Order. According to an essay on the website of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, "Historians generally concur that Joseph Smith approved of the Danites but that he probably was not briefed on all their plans and likely did not sanction the full range of their activities."

The Evening and the Morning Star was an early Latter Day Saint movement newspaper published monthly in Independence, Missouri, from June 1832 to July 1833, and then in Kirtland, Ohio, from December 1833 to September 1834. Reprints of edited versions of the original issues were also published in Kirtland under the title Evening and Morning Star.

The Latter Day Saint movement is a religious movement within Christianity that arose during the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century and that led to the set of doctrines, practices, and cultures called Mormonism, and to the existence of numerous Latter Day Saint churches. Its history is characterized by intense controversy and persecution in reaction to some of the movement's doctrines and practices and their relationship to mainstream Christianity. The purpose of this article is to give an overview of the different groups, beliefs, and denominations that began with the influence of Joseph Smith.

The 1838 Mormon War, also known as the Missouri Mormon War, was a conflict between Mormons and their neighbors in Missouri. It was preceded by tensions and episodes of vigilante violence dating back to the initial Mormon settlement in Jackson County in 1831. State troops became involved after the Battle of Crooked River, leading Governor Lilburn Boggs to order Mormons expelled from the state. It should not be confused with the Illinois Mormon War or the Utah War.

Missouri Executive Order 44 was a state executive order issued by Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs on October 27, 1838, in response to the Battle of Crooked River. The clash had been triggered when a state militia unit from Ray County seized several Mormon hostages from Caldwell County, and the subsequent attempt by the Mormons to rescue them.

Lyman Wight was an early leader in the Latter Day Saint movement. He was the leader of the Latter Day Saints in Daviess County, Missouri, in 1838. In 1841, he was ordained a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. After the death of Joseph Smith resulted in a succession crisis, Wight led his own break-off group of Latter Day Saints to Texas, where they created a settlement. While in Texas, Wight broke with the main body of the group led by Brigham Young. Wight was ordained president of his own church, but he later sided with the claims of William Smith, and eventually of Joseph Smith III. After his death, most of the "Wightites" joined with the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

Far West was a settlement of the Latter Day Saint movement in Caldwell County, Missouri, United States, during the late 1830s. It is recognized as a historic site by the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, added to the register in 1970. It is owned and maintained by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Battle of Crooked River was a skirmish occurred on October 25, 1838, a major escalator of the 1838 Mormon War. A Mormon rescue party, led by David W. Patten, formed to free three Mormon captives taken from Caldwell County the day prior, clashed with a Ray County militia company commanded by Samuel Bogart southeast of Elmira, Missouri. Exaggerated reports of the battle led Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs to issue Missouri executive order 44, resulting in the forced expulsion of the Mormons from the state.

Zion's Camp was an expedition of Latter Day Saints led by Joseph Smith, from Kirtland, Ohio, to Clay County, Missouri, during May and June 1834 in an unsuccessful attempt to regain land from which the Saints had been expelled by non-Mormon settlers. In Latter Day Saint belief, this land is destined to become a city of Zion, the center of the millennial kingdom; and Smith dictated a command from God ordering him to lead his church like a modern Moses to redeem Zion "by power, and with a stretched-out arm."

Hiram Page was an early member of the Latter Day Saint movement and one of the Eight Witnesses to the Book of Mormon's golden plates.

William Wines Phelps was an American author, composer, politician, and early leader of the Latter Day Saint movement. He printed the first edition of the Book of Commandments that became a standard work of the church and wrote numerous hymns, some of which are included in the current version of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' hymnal. He was at times both close to and at odds with church leadership. He testified against Joseph Smith, providing evidence that helped persuade authorities to arrest Smith. He was excommunicated three times and rejoined the church each time. He was a ghostwriter for Smith. Phelps was called by Smith to serve as assistant president of the church in Missouri and as a member of the Council of Fifty. After Smith's death, Phelps supported Brigham Young, who was the church's new president.

Within the Latter Day Saint movement, Zion is often used to connote an association of the righteous. This association would practice a form of communitarian economics, called the United Order, which were meant to ensure that all members maintained an acceptable quality of life, class distinctions were minimized, and group unity achieved.

Daniel Dunklin was the fifth Governor of Missouri, serving from 1832 to 1836. He also served as the state's third Lieutenant Governor. Dunklin is considered the "Father of Public Schools" in Missouri. Dunklin was also the father-in-law of Missouri Lieutenant Governor Franklin Cannon. Dunklin County, in the Missouri bootheel, is named so in his honor.

John Corrill was an early member and leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and an elected representative in the Missouri State Legislature. He was prominently involved in the Mormon conflicts in Missouri before leaving the church in 1839 and publishing A Brief History of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints .

The life of Joseph Smith from 1838 to 1839, when he was 33–34 years old, covers a period beginning when Smith left Ohio in January 1838 until he left Missouri and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois in 1839.

The history of the Latter Day Saint movement includes numerous instances of violence. Mormons faced significant persecution in the early 19th century, including instances of forced displacement and mob violence in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. Notably, the founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, was shot and killed alongside his brother, Hyrum Smith, in Carthage, Illinois in 1844, while Smith was in jail awaiting trial on charges of treason and inciting a riot.

The Temple Lot, located in Independence, Missouri, is the first site to be dedicated for the construction of a temple in the Latter Day Saint movement. The area was dedicated on August 3, 1831, by the movement's founder, Joseph Smith. It was purchased on December 19, 1831, by Edward Partridge to be the center of the New Jerusalem or "City of Zion" after Smith said he received a revelation stating that it would be the gathering spot of the Latter Day Saints during the last days.

Joseph Smith Jr. was an American religious leader and the founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. Publishing the Book of Mormon at the age of 24, Smith attracted tens of thousands of followers by the time of his death fourteen years later. The religion he founded is followed to the present day by millions of global adherents and several churches, the largest of which is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Algernon Sidney Gilbert was a merchant best known for his involvement with Latter-day Saint history and his partnership with Newel K. Whitney in Kirtland, Ohio. He is mentioned in seven sections of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Doctrine and Covenants. He was ordained as a high priest in the state of Missouri and served as a missionary in the United States.

The life of Joseph Smith, Jr. from 1831 to 1837, when he was 26–32 years old, covers the period of time from when Smith moved with his family to Kirtland, Ohio, in 1831, until he left Ohio for Missouri early in early January 1838. By 1831, Smith had already published the Book of Mormon, and established the Latter Day Saint movement. He had founded it as the Church of Christ, but eventually dictated a revelation to change its name to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.