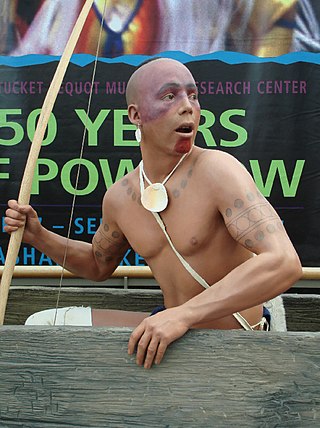

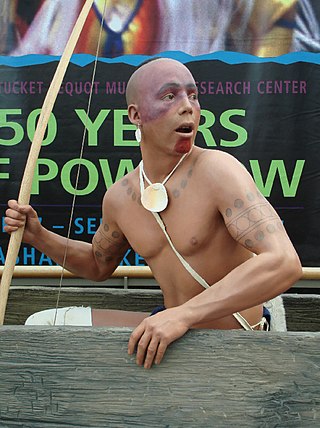

The Pequot are a Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut including the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, or the Brothertown Indians of Wisconsin. They historically spoke Pequot, a dialect of the Mohegan-Pequot language, which became extinct by the early 20th century. Some tribal members are undertaking revival efforts.

The Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation is a federally recognized American Indian tribe in the state of Connecticut. They are descended from the Pequot people, an Algonquian-language tribe that dominated the southern New England coastal areas, and they own and operate Foxwoods Resort Casino within their reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut. As of 2018, Foxwoods Resort Casino is one of the largest casinos in the world in terms of square footage, casino floor size, and number of slot machines, and it was one of the most economically successful in the United States until 2007, but it became deeply in debt by 2012 due to its expansion and changing conditions.

Scouting in Connecticut has experienced many organizational changes since 1910. With only eight counties, Connecticut has had 40 Boy Scout Councils since the Scouting movement began in 1910. In 1922, 17 Boy Scout Councils existed in Connecticut, but currently only four exist. The Girl Scouts of the USA has had at least 53 Girl Scout Councils in Connecticut since their program began in 1912. Today there is one, Girl Scouts of Connecticut, which assumed operation on October 1, 2007.

Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in Groton and Stonington, Connecticut.

King Philip's War was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, the English New England Colonies and their indigenous allies. The war is named for Metacom, the Pokanoket chief and sachem of the Wampanoag who adopted the English name Philip because of the friendly relations between his father Massasoit and the Plymouth Colony. The war continued in the most northern reaches of New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay on April 12, 1678.

Uncas was a sachem of the Mohegans who made the Mohegans the leading regional Indian tribe in lower Connecticut, through his alliance with the New England colonists against other Indian tribes.

The Pequot War was an armed conflict that took place in 1636 and ended in 1638 in New England, between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of the colonists from the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes. The war concluded with the decisive defeat of the Pequot. At the end, about 700 Pequots had been killed or taken into captivity. Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to colonists in Bermuda or the West Indies; other survivors were dispersed as captives to the victorious tribes.

Roger Ludlow (1590–1664) was an English lawyer, magistrate, military officer, and colonist. He was active in the founding of the Colony of Connecticut, and helped draft laws for it and the nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony. Under his and John Mason's direction, Boston's first fortification, later known as Castle William and then Fort Independence was built on Castle Island in Boston harbor. Frequently at odds with his peers, he eventually also founded Fairfield and Norwalk before leaving New England entirely.

John Mason was an English-born settler, soldier, commander and Deputy Governor of the Connecticut Colony. Mason was best known for leading a group of Puritan settlers and Indian allies on a combined attack on a Pequot Fort in an event known as the Mystic Massacre. The destruction and loss of life he oversaw effectively ended the hegemony of the Pequot tribe in southeast Connecticut.

Southport is a census-designated place (CDP) in the town of Fairfield, Connecticut. It is located along Long Island Sound between Mill River and Sasco Brook, where it borders Westport. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 1,710. Settled in 1639, Southport center has been designated a local historic district since 1967. In 1971, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Southport Historic District.

Sassacus was a Pequot sachem who was born near present-day Groton, Connecticut. He became grand sachem after his father, Tatobem, was killed in 1632. The Mohegans led by sachem Uncas rebelled against domination by the Pequots. Sassacus and the Pequots were defeated by English colonists allied with the Narragansett and Mohegans in the Pequot War.

The Mystic massacre – also known as the Pequot massacre and the Battle of Mystic Fort – took place on May 26, 1637 during the Pequot War, when a force from the Connecticut Colony under Captain John Mason and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies set fire to the Pequot Fort near the Mystic River. They shot anyone who tried to escape the wooden palisade fortress and killed most of the village. There were between 400 and 700 Pequots killed during the attack; the only Pequot survivors were warriors who were away in a raiding party with their sachem Sassacus.

The Great Swamp Massacre or the Great Swamp Fight was a crucial battle fought during King Philip's War between the colonial militia of New England and the Narragansett people in December 1675. It was fought near the villages of Kingston and West Kingston in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. The combined force of the New England militia included 150 Pequots, and they inflicted a huge number of Narragansett casualties, including many hundreds of women and children. The battle has been described as "one of the most brutal and lopsided military encounters in all of New England's history."

The Pequot Fort was a fortified Native American village in what is now the Groton side of Mystic, Connecticut, United States. Located atop a ridge overlooking the Mystic River, it was a palisaded settlement of the Pequot tribe until its destruction by Puritan and Mohegan forces in the 1637 Mystic massacre during the Pequot War. The exact location of its archaeological remains is not certain, but it is commemorated by a small memorial at Pequot Avenue and Clift Street. The site previously included a statue of Major John Mason, who led the forces that destroyed the fort; it was removed in 1995 after protests by Pequot tribal members. The archaeological site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.

Wequash Cooke was allegedly one of the earliest Native American converts to Protestant Christianity, and as a sagamore he played an important role in the 1637 Pequot War in New England.

The Battle of Turner's Falls or Battle of Grand Falls; also known as the Peskeompscut-Wissantinnewag Massacre, was a battle and massacre occurring on May 19, 1676, in the context of King Philip's War in what is present-day Gill and Greenfield, across from Turners Falls on the Connecticut River. The incident marked a turning point in the war, and in the colonization of Native lands by British settlers. The war led to the expulsion of most Native Americans in the Connecticut River Valley.

The Second Battle of Nipsachuck Battlefield is a historic military site in North Smithfield, Rhode Island. A largely swampy terrain, it is the site of one of the last battles of King Philip's War to be fought in southern New England, on July 2, 1676. The battle is of interest to military historians because it included a rare use in the war of a cavalry charge by the English colonists. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Harman Garrett was a Niantic sachem and then governor of the Eastern Pequots slightly east of the Pawcatuck River in what is now Westerly, Rhode Island. His chosen English name was very similar to that of Herman Garrett, a prominent colonial gunsmith from Massachusetts in the 1650s.

Rev. Hope Atherton (1646–1677) was a colonial clergyman. He was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Harvard Class of 1665. He was the minister of Hadley, Massachusetts. He served as a chaplain in the King Philips War and became separated from troops during the Battle of Great Falls in 1676. He died months after the battle, aged 30.

Quaiapen was a Narragansett-Niantic female sachem (saunkskwa) who was the last sachem captured or killed during King Philip’s War.