The 1890s was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1890, and ended on December 31, 1899. In American popular culture, the decade would later be nostalgically referred to as the "Gay Nineties". In the British Empire, the 1890s epitomised the late Victorian period.

Herman Webster Mudgett, better known as Dr. Henry Howard Holmes or H. H. Holmes, was an American con artist and serial killer active between 1891 and 1894. By the time of his execution in 1896, Holmes had engaged in a lengthy criminal career that included insurance fraud, forgery, swindling, three or four bigamous marriages, horse theft, and murder. His most notorious crimes took place in Chicago around the time of the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893.

Abel Beach was an American poet, attorney, state auditor, and college professor. He was one of the six founders of the international fraternity Theta Delta Chi.

Winifred Sweet Black Bonfils was an American reporter and columnist, under the pen name Annie Laurie, a reference to her mother's favorite lullaby. She also wrote under the name Winifred Black.

William Edward Sawyer was an American inventor whose contribution was primarily in the field of electric engineering and electric lighting.

Albert Griffiths, better known as Young Griffo, was a World Featherweight boxing champion from 1890 to 1892, and according to many sources, one of the first boxing world champions in any class. Ring magazine founder Nat Fleischer rated Griffo as the eighth greatest featherweight of all time. He was inducted into the Ring Magazine Hall of Fame in 1954, the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1991, and the Australian National Boxing Hall of Fame in 2003.

Edward W. Dowling, better known as Robert Joseph Glenalvin, was an American professional baseball second baseman and manager. He played for the Chicago Colts of the National League in the 1890 and 1893 seasons. His professional career in Minor League Baseball spanned from the 1887 to 1899 seasons, where he served as the player-manager for several minor league teams. Glenalvin was also an umpire in the minor leagues from the 1909 through 1914 seasons.

George Burlingame "Dygie" Dygert was an American football player and coach and lawyer. Dygert played college football for the University of Michigan for five years, from 1890 to 1894, and was captain of the 1892 and 1893 teams. He played professional football for the Butte, Montana, football team in 1896 and 1897 and practiced law in Butte and Chicago from 1896 to 1953.

The Sunday Mercury (1839–1896) was a weekly Sunday newspaper published in New York City that grew to become the highest-circulation weekly newspaper in the United States at its peak. It was known for publishing and popularizing the work of many notable 19th-century writers, including Charles Farrar Browne and Robert Henry Newell, and was the first Eastern paper to publish Mark Twain. It was also the first newspaper to provide regular coverage of baseball, and was popular for the extensive war correspondence from soldiers it published during the Civil War.

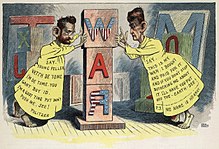

Harold Robertson Heaton was a newspaper artist whose work focused on cartoons. His prodigious body of work contributed to the development of political cartoons. He also illustrated books and produced sketches and paintings. He left newspaper work in 1899 to begin acting on the stage, and later wrote plays as well. He returned to cartooning for six years beginning in 1908, but continued acting while doing so. He appeared in many Broadway productions through 1932. A brief retrospective on his employment with the Chicago Tribune, from October 1942, mentioned his obituary had been printed "a few years ago".

The History of Michigan Wolverines football in the early years covers the history of the University of Michigan Wolverines football program from its formation in the 1870s through the hiring of Fielding H. Yost prior to the 1901 season. Michigan was independent of any conference until 1896 when it became one of the founding members of the Western Conference. The team played its home games at the Washtenaw County Fairgrounds from 1883 to 1892 and then at Regents Field starting in 1893.

This page contains a selected list of press headlines relevant to the Armenian genocide in chronological order, as recorded in newspaper archives. The sources prior to 1914 relate in large part to the Hamidian massacres and the Adana massacre.

The Pittsburgh Refrigerator Cat, Refrigerator Cat, Cold Storage Cat or Eskimo Cat is repeated as fact in many cat books. However, this never existed as a breed. Although refrigerator cats are frequently described as a lost longhaired breed, the reports describe them as thick-furred.

False information in the United States has been a subject of discussion and debate, especially since the increased reliance on the Internet and social media for information.

Lydia Arms Avery Coonley-Ward was a social leader, clubwoman and writer. Coonley served as a president of the Chicago Women's Club and was known for her poetry. She also helped her second husband, Henry Augustus Ward, enlarge his meteorite collection.

The Yampa was an American ocean-going cruising schooner yacht for pleasure use from 1887 to 1899. The yacht was originally built for Chester W. Chapin, a rail baron and U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts. It completed several ocean cruises with no accidents. It passed through several hands and ultimately was purchased by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany as a birthday present for his wife. He had another larger yacht built based on the design of the Yampa, which was named the Meteor III.

John Harrison Mills was an American artist, businessman and philanthropist who worked in Buffalo, New York, and in Colorado. While he considered himself to be foremost a painter, he also worked in sculpture, sketches, poetry and other writings. His primary occupation was an engraver, making illustrations for publications of the day. He was a partner in a lithography business and an engraving/publishing business, and founded a shipping company for artists.

Laura Rosamond White was an American author and editor whose work was affiliated with the Woman's Relief Corps, Woman's Christian Temperance Union (W.C.T.U.), and the Non-Partisan National Woman's Christian Temperance Union. She was also regarded as the poet of Geneva, Ohio, and served as city editor of the Geneva Times.

Paul Armstrong was an American playwright, whose melodramas provided thrills and comedy to audiences in the first fifteen years of the 20th century. Originally a steamship captain, he went into journalism, became a press agent, then a full time playwright. His period of greatest success was from 1907 through 1911, when his four-act melodramas Salomy Jane (1907), Via Wireless (1908), Going Some (1909), Alias Jimmy Valentine (1909), The Deep Purple (1910), and The Greyhound (1911), had long runs on Broadway and in touring companies. Many of his plays were adapted for silent films between 1914 and 1928.