The earliest texts of William Shakespeare's works were published during the 16th and 17th centuries in quarto or folio format. Folios are large, tall volumes; quartos are smaller, roughly half the size. The publications of the latter are usually abbreviated to Q1, Q2, etc., where the letter stands for "quarto" and the number for the first, second, or third edition published.

Pericles, Prince of Tyre is a Jacobean play written at least in part by William Shakespeare and included in modern editions of his collected works despite questions over its authorship, as it was not included in the First Folio. It was published in 1609 as a quarto, was not included in Shakespeare's collections of works until the third folio, and the main inspiration for the play was Gower's Confessio Amantis. Various arguments support the theory that Shakespeare was the sole author of the play, notably in DelVecchio and Hammond's Cambridge edition of the play, but modern editors generally agree that Shakespeare was responsible for almost exactly half the play — 827 lines — the main portion after scene 9 that follows the story of Pericles and Marina. Modern textual studies suggest that the first two acts, 835 lines detailing the many voyages of Pericles, were written by a collaborator, who may well have been the victualler, panderer, dramatist and pamphleteer George Wilkins. Wilkins published The Painful Adventures of Pericles Prince of Tyre which is the prose version of the story, and drew from Lawrence Twines' The Pattern of Painful Adventures. Pericles was one of the seventeen plays that were in print during Shakespeare's life, and was reprinted 5 times between 1609 and 1635.

This article presents a possible chronological listing of the composition of the plays of William Shakespeare.

The Shakespeare apocrypha is a group of plays and poems that have sometimes been attributed to William Shakespeare, but whose attribution is questionable for various reasons. The issue is not to be confused with the debate on Shakespearean authorship, which questions the authorship of the works traditionally attributed to Shakespeare.

Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies is a collection of plays by William Shakespeare, commonly referred to by modern scholars as the First Folio, published in 1623, about seven years after Shakespeare's death. It is considered one of the most influential books ever published.

Sir John Oldcastle is an Elizabethan play about John Oldcastle, a controversial 14th-/15th-century rebel and Lollard who was seen by some of Shakespeare's contemporaries as a proto-Protestant martyr.

A Yorkshire Tragedy is an early Jacobean era stage play, a domestic tragedy printed in 1608. The play was originally assigned to William Shakespeare, though the modern critical consensus rejects this attribution, favouring Thomas Middleton.

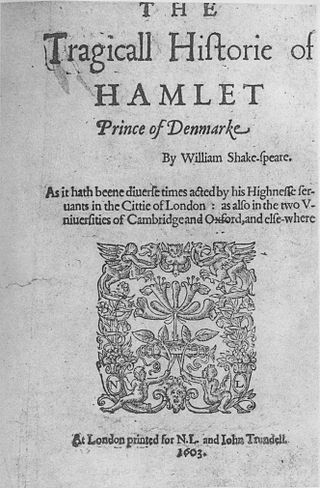

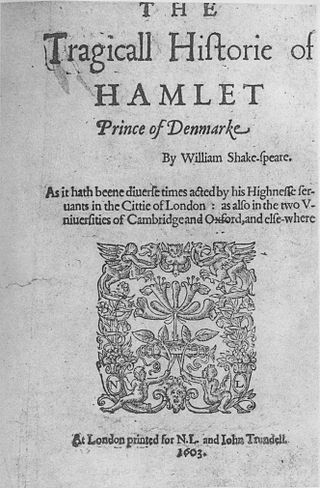

A bad quarto, in Shakespearean scholarship, is a quarto-sized printed edition of one of Shakespeare's plays that is considered to be unauthorised, and is theorised to have been pirated from a theatrical performance without permission by someone in the audience writing it down as it was spoken or, alternatively, written down later from memory by an actor or group of actors in the cast – the latter process has been termed "memorial reconstruction". Since the quarto derives from a performance, hence lacks a direct link to the author's original manuscript, the text would be expected to be "bad", i.e. to contain corruptions, abridgements and paraphrasings.

William Jaggard was an Elizabethan and Jacobean printer and publisher, best known for his connection with the texts of William Shakespeare, most notably the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays. Jaggard's shop was "at the sign of the Half-Eagle and Key in Barbican."

Valentine Simmes was an Elizabethan era and Jacobean era printer; he did business in London, "on Adling Hill near Bainard's Castle at the sign of the White Swan." Simmes has a reputation as one of the better printers of his generation, and was responsible for several quartos of Shakespeare's plays. [See: Early texts of Shakespeare's works.]

Thomas Creede was a printer of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, rated as "one of the best of his time." Based in London, he conducted his business under the sign of the Catherine Wheel in Thames Street from 1593 to 1600, and under the sign of the Eagle and Child in the Old Exchange from 1600 to 1617. Creede is best known for printing editions of works in English Renaissance drama, especially for ten editions of six Shakespearean plays and three works in the Shakespeare Apocrypha.

William Aspley was a London publisher of the Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline eras. He was a member of the publishing syndicates that issued the First Folio and Second Folio collections of Shakespeare's plays, in 1623 and 1632.

John Smethwick was a London publisher of the Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline eras. Along with colleague William Aspley, Smethwick was one of the "junior partners" in the publishing syndicate that issued the First Folio collection of Shakespeare's plays in 1623. As his title pages specify, his shop was "in St. Dunstan's Churchyard in Fleet Street, under the Dial."

Thomas Cotes was a London printer of the Jacobean and Caroline eras, best remembered for printing the Second Folio edition of Shakespeare's plays in 1632.

Thomas Millington was a London publisher of the Elizabethan era, who published first editions of three Shakespearean plays. He has been called a "stationer of dubious reputation" who was connected with some of the "bad quartos" and questionable texts of Shakespearean bibliography.

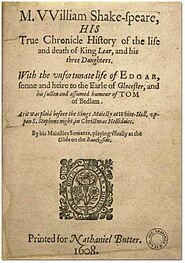

Nathaniel Butter was a London publisher of the early 17th century. As the publisher of the first edition of Shakespeare's King Lear in 1608, he has also been regarded as one of the first publishers of a newspaper in English.

Thomas Pavier was a London publisher and bookseller of the early seventeenth century. His complex involvement in the publication of early editions of some of Shakespeare's plays, as well as plays of the Shakespeare Apocrypha, has left him with a "dubious reputation."

Thomas Heyes was the publisher-bookseller who published the first quarto edition of William Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, in London, in 1600. He traded from 'St Paul’s Churchyard at the sign of the Green Dragon’.

James Roberts, was an English printer who printed many important works of Elizabethan literature. F. G. Fleay says that "he seems to have been given to piracy and invasion of copyright".