Related Research Articles

Archaeopteryx, sometimes referred to by its German name, "Urvogel" is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaīos), meaning "ancient", and πτέρυξ (ptéryx), meaning "feather" or "wing". Between the late 19th century and the early 21st century, Archaeopteryx was generally accepted by palaeontologists and popular reference books as the oldest known bird. Older potential avialans have since been identified, including Anchiornis, Xiaotingia, and Aurornis.

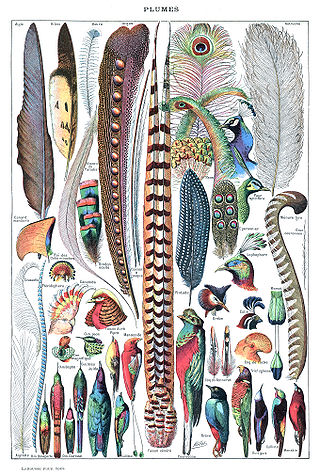

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and an example of a complex evolutionary novelty. They are among the characteristics that distinguish the extant birds from other living groups.

A pin feather is a developing feather on a bird. This feather can grow as a new feather during the bird's infancy, or grow to replace one from moulting.

Sinosauropteryx is a compsognathid dinosaur. Described in 1996, it was the first dinosaur taxon outside of Avialae to be found with evidence of feathers. It was covered with a coat of very simple filament-like feathers. Structures that indicate colouration have also been preserved in some of its feathers, which makes Sinosauropteryx the first non-avialian dinosaurs where colouration has been determined. The colouration includes a reddish and light banded tail. Some contention has arisen with an alternative interpretation of the filamentous impression as remains of collagen fibres, but this has not been widely accepted.

Microraptor is a genus of small, four-winged dromaeosaurid dinosaurs. Numerous well-preserved fossil specimens have been recovered from Liaoning, China. They date from the early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation, 125 to 120 million years ago. Three species have been named, though further study has suggested that all of them represent variation in a single species, which is properly called M. zhaoianus. Cryptovolans, initially described as another four-winged dinosaur, is usually considered to be a synonym of Microraptor.

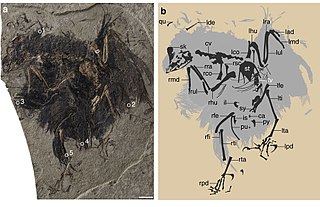

Confuciusornis is a genus of basal crow-sized avialan from the Early Cretaceous Period of the Yixian and Jiufotang Formations of China, dating from 125 to 120 million years ago. Like modern birds, Confuciusornis had a toothless beak, but closer and later relatives of modern birds such as Hesperornis and Ichthyornis were toothed, indicating that the loss of teeth occurred convergently in Confuciusornis and living birds. It was thought to be the oldest known bird to have a beak, though this title now belongs to an earlier relative Eoconfuciusornis. It was named after the Chinese moral philosopher Confucius. Confuciusornis is one of the most abundant vertebrates found in the Yixian Formation, and several hundred complete specimens have been found.

Maniraptora is a clade of coelurosaurian dinosaurs which includes the birds and the non-avian dinosaurs that were more closely related to them than to Ornithomimus velox. It contains the major subgroups Avialae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae, Oviraptorosauria, and Therizinosauria. Ornitholestes and the Alvarezsauroidea are also often included. Together with the next closest sister group, the Ornithomimosauria, Maniraptora comprises the more inclusive clade Maniraptoriformes. Maniraptorans first appear in the fossil record during the Jurassic Period, and survive today as living birds.

The pennaceous feather is a type of feather present in most modern birds and in some other species of maniraptoriform dinosaurs.

A feathered dinosaur is any species of dinosaur possessing feathers. That includes all species of birds, and in recent decades evidence has accumulated that many non-avian dinosaur species also possessed feathers in some shape or form. The extent to which feathers or feather-like structures were present in dinosaurs as a whole is a subject of ongoing debate and research.

Sinornithosaurus is a genus of feathered dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the early Cretaceous Period of the Yixian Formation in what is now China. It was the fifth non–avian feathered dinosaur genus discovered by 1999. The original specimen was collected from the Sihetun locality of western Liaoning. It was found in the Jianshangou beds of the Yixian Formation, dated to 124.5 million years ago. Additional specimens have been found in the younger Dawangzhangzi bed, dating to around 122 million years ago.

Bird flight is the primary mode of locomotion used by most bird species in which birds take off and fly. Flight assists birds with feeding, breeding, avoiding predators, and migrating.

Odontognathae is a disused name for a paraphyletic group of toothed prehistoric birds. The group was originally proposed by Alexander Wetmore, who attempted to link fossil birds with the presence of teeth, specifically of the orders Hesperornithiformes and Ichthyornithiformes. As such they would be regarded as transitional fossils between the reptile-like "Archaeornithes" like Archaeopteryx and modern birds. They were described by Romer as birds with essentially modern anatomy, but retaining teeth.

The scientific question of within which larger group of animals birds evolved has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated during the Mesozoic era.

Anchiornis is a genus of small, four-winged paravian dinosaurs, with only one known species, the type species Anchiornis huxleyi, named for its similarity to modern birds. The Latin name Anchiornis derives from a Greek word meaning "near bird", and huxleyi refers to Thomas Henry Huxley, a contemporary of Charles Darwin.

Praeornis is an extinct genus of early avialan, possibly an enantiornithine, from the Late Jurassic Karabastau Formation of Kazakhstan. Only the type species is known, which is P. sharovi.

The Origin of Birds is an early synopsis of bird evolution written in 1926 by Gerhard Heilmann, a Danish artist and amateur zoologist. The book was born from a series of articles published between 1913 and 1916 in Danish, and although republished as a book it received mainly criticism from established scientists and got little attention within Denmark. The English edition of 1926, however, became highly influential at the time due to the breadth of evidence synthesized as well as the artwork used to support its arguments. It was considered the last word on the subject of bird evolution for several decades after its publication.

The following is a glossary of common English language terms used in the description of birds—warm-blooded vertebrates of the class Aves and the only living dinosaurs. Birds, who have feathers and the ability to fly, are toothless, have beakedjaws, lay hard-shelled eggs, and have a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweight skeleton.

Serikornis is a genus of small, feathered anchiornithid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Liaoning, China. It is represented by the type species Serikornis sungei.

Cruralispennia is an extinct genus of enantiornithean bird. The only known specimen of Cruralispennia was discovered in the Early Cretaceous Huajiying Formation of China and formally described in 2017. The type species of Cruralispennia is Cruralispennia multidonta. The generic name is Latin for "shin feather", while the specific name means "many-toothed". The holotype of Cruralispennia is IVPP 21711, a semi-articulated partial skeleton surrounded by the remains of carbonized feathers.

Caihong is a genus of small paravian theropod dinosaur from China that lived during the Late Jurassic period.

References

- 1 2 Kardong, Kenneth (2014). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, and Evolution. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0078023026.

- 1 2 3 Zimmer, Carl (2013). The Tangled Bank. Roberts and Company. ISBN 978-1936221448.

- ↑ Xu, Xing (2008). "A new feather type in a nonavian theropod and the early evolution of feathers" (PDF). PNAS. 106 (3): 832–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810055106 . PMC 2630069 . PMID 19139401.

- ↑ "Bird Feather Types, Anatomy, Molting, Growth, and Color". www.peteducation.com. Archived from the original on 2017-02-09. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ "Everything You Need To Know About Feathers". www.allaboutbirds.org. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ↑ "Types of Bird Feathers". www.paulnoll.com. Retrieved 2023-07-27.