The Toltec culture was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, reaching prominence from 950 to 1150 CE. The later Aztec culture considered the Toltec to be their intellectual and cultural predecessors and described Toltec culture emanating from Tōllān as the epitome of civilization. In the Nahuatl language the word Tōltēkatl (singular) or Tōltēkah (plural) came to take on the meaning "artisan". The Aztec oral and pictographic tradition also described the history of the Toltec Empire, giving lists of rulers and their exploits.

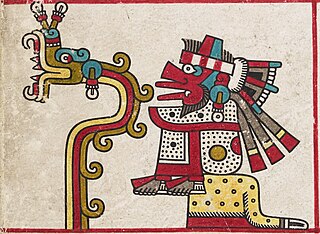

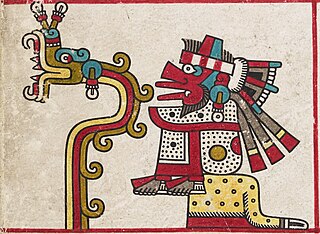

Ehecatl is a pre-Columbian deity associated with the wind, who features in Aztec mythology and the mythologies of other cultures from the central Mexico region of Mesoamerica. He is most usually interpreted as the aspect of the Feathered Serpent deity as a god of wind, and is therefore also known as Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. Ehecatl also figures prominently as one of the creator gods and culture heroes in the mythical creation accounts documented for pre-Columbian central Mexican cultures.

The Olmecs or Olmec were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing in the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco from roughly 1200 to 400 BCE during Mesoamerica's formative period. They were initially centered at the site of their development in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, but moved to La Venta in the 10th century BCE following the decline of San Lorenzo. The Olmecs disappeared mysteriously in the 4th century BCE, leaving the region sparsely populated until the 19th century.

Teotihuacan is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, 40 kilometers (25 mi) northeast of modern-day Mexico City.

The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan is a proposed goddess of the pre-Columbian Teotihuacan civilization, in what is now Mexico.

Mesoamerican chronology divides the history of prehispanic Mesoamerica into several periods: the Paleo-Indian ; the Archaic, the Preclassic or Formative (2500 BCE – 250 CE), the Classic (250–900 CE), and the Postclassic (900–1521 CE); as well as the post European contact Colonial Period (1521–1821), and Postcolonial, or the period after independence from Spain (1821–present).

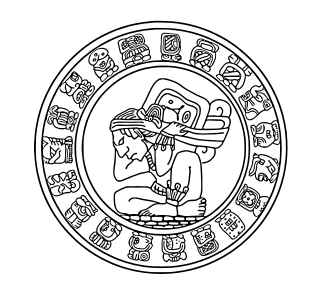

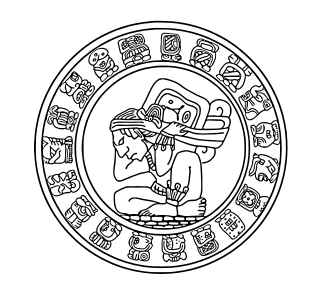

The calendrical systems devised and used by the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily a 260-day year, were used in religious observances and social rituals, such as divination.

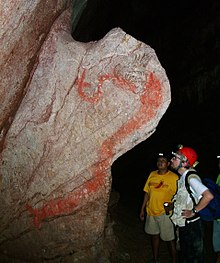

The religion of the Olmec people significantly influenced the social development and mythological world view of Mesoamerica. Scholars have seen echoes of Olmec supernatural in the subsequent religions and mythologies of nearly all later pre-Columbian era cultures.

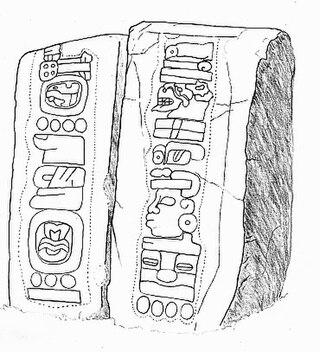

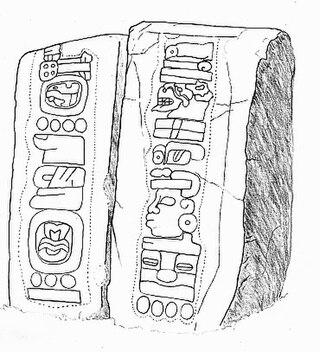

Mesoamerican pyramids form a prominent part of ancient Mesoamerican architecture. Although similar in some ways to Egyptian pyramids, these New World structures have flat tops and stairs ascending their faces, more similar to ancient Mesopotamian Ziggurats. The largest pyramid in the world by volume is the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the east-central Mexican state of Puebla. The builders of certain classic Mesoamerican pyramids have decorated them copiously with stories about the Hero Twins, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, Mesoamerican creation myths, ritualistic sacrifice, etc. written in the form of Maya script on the rises of the steps of the pyramids, on the walls, and on the sculptures contained within.

K’uk’ulkan, also spelled Kukulkan, is the serpent deity of Maya mythology. It is closely related to the deity Qʼuqʼumatz of the Kʼicheʼ people and to Quetzalcoatl of Aztec mythology. Prominent temples to Kukulkan are found at archaeological sites in the Yucatán Peninsula, such as Chichen Itza, Uxmal and Mayapan.

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent is the third largest pyramid at Teotihuacan, a pre-Columbian site in central Mexico. This pre-Columbian city rose around the first or second century BCE and its occupation prolonged through to the 600s or 700s. Early growth of the population was relatively quick, with an estimated population of 60,000-80,000 inhabitants; it is suggested that the population reached up to 100,000 by the 300s

Mesoamerican creation myths are the collection of creation myths attributed to, or documented for, the various cultures and civilizations of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Mesoamerican literature.

World trees are a prevalent motif occurring in the mythical cosmologies, creation accounts, and iconographies of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica. In the Mesoamerican context, world trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which also serve to represent the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi that connects the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial realm.

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures.

Mesoamerican architecture is the set of architectural traditions produced by pre-Columbian cultures and civilizations of Mesoamerica, traditions which are best known in the form of public, ceremonial and urban monumental buildings and structures. The distinctive features of Mesoamerican architecture encompass a number of different regional and historical styles, which however are significantly interrelated. These styles developed throughout the different phases of Mesoamerican history as a result of the intensive cultural exchange between the different cultures of the Mesoamerican culture area through thousands of years. Mesoamerican architecture is mostly noted for its pyramids, which are the largest such structures outside of Ancient Egypt.

Karl Andreas Taube is an American Mesoamericanist, Mayanist, iconographer and ethnohistorian, known for his publications and research into the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica and the American Southwest. He is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, University of California, Riverside. In 2008 he was named the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences distinguished lecturer.

The werejaguar was both an Olmec motif and a supernatural entity, perhaps a deity.

In Mesoamerican culture, Tonatiuh is an Aztec sun deity of the daytime sky who rules the cardinal direction of east. According to Aztec Mythology, Tonatiuh was known as "The Fifth Sun" and was given a calendar name of naui olin, which means "4 Movement". Represented as a fierce and warlike god, he is first seen in Early Postclassic art of the Pre-Columbian civilization known as the Toltec. Tonatiuh's symbolic association with the eagle alludes to the Aztec belief of his journey as the present sun, travelling across the sky each day, where he descended in the west and ascended in the east. It was thought that his journey was sustained by the daily sacrifice of humans. His Nahuatl name can also be translated to "He Who Goes Forth Shining" or "He Who Makes The Day." Tonatiuh was thought to be the central deity on the Aztec calendar stone but is no longer identified as such. In Toltec culture, Tonatiuh is often associated with Quetzalcoatl in his manifestation as the morning star aspect of the planet Venus.

Quetzalcoatl is a deity in Aztec culture and literature. Among the Aztecs, he was related to wind, Venus, Sun, merchants, arts, crafts, knowledge, and learning. He was also the patron god of the Aztec priesthood. He was one of several important gods in the Aztec pantheon, along with the gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli. The two other gods represented by the planet Venus are Tlaloc and Xolotl.

The use of mirrors in Mesoamerican culture was associated with the idea that they served as portals to a realm that could be seen but not interacted with. Mirrors in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from the decorative to the divinatory. An ancient tradition among many Mesoamerican cultures was the practice of divination using the surface of a bowl of water as a mirror. At the time of the Spanish conquest this form of divination was still practiced among the Maya, Aztecs and Purépecha. In Mesoamerican art, mirrors are frequently associated with pools of liquid; this liquid was likely to have been water.