See also

- Serendipity, a benefit that is accidentally earned

- Silver lining

Felix culpa is a Latin phrase that comes from the words felix, meaning "happy," "lucky," or "blessed" and culpa, meaning "fault" or "fall". In the Catholic tradition, the phrase is most often translated "happy fault", as in the Catholic Exsultet. Other translations include "blessed fall" or "fortunate fall". [1]

As a theological concept, felix culpa is a way of understanding the Fall as having positive outcomes, such as the redemption of mankind through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. [2] The concept is paradoxical in nature as it looks at the fortunate consequences of an unfortunate event, which would never have been possible without the unfortunate event in the first place. [3] In the philosophy of religion, felix culpa is considered as a category of theodicy explaining why God would create man with the capacity to fall in the first place. As an interpretation of the Fall, the concept differs from orthodox interpretations which often emphasize negative aspects of the Fall, such as Original Sin. Although it is usually discussed historically, there are still contemporary philosophers, such as Alvin Plantinga, who defend the felix culpa theodicy. [4]

The earliest known use of the term appears in the Catholic Paschal Vigil Mass Exsultet: O felix culpa quae talem et tantum meruit habere redemptorem, "O happy fault that earned for us so great, so glorious a Redeemer." [5] In the 4th century, Saint Ambrose also speaks of the fortunate ruin of Adam in the Garden of Eden in that his sin brought more good to humanity than if he had stayed perfectly innocent. [6] This theology is continued in the writings of Ambrose's student St. Augustine regarding the Fall of Man, the source of original sin: “For God judged it better to bring good out of evil than not to permit any evil to exist.” (in Latin: Melius enim iudicavit de malis benefacere, quam mala nulla esse permittere.) [7] The medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas [8] cited this line when he explained how the principle that "God allows evils to happen in order to bring a greater good therefrom" underlies the causal relation between original sin and the Divine Redeemer's Incarnation, thus concluding that a higher state is not inhibited by sin.

In the 14th century, John Wycliffe refers to the fortunate fall in his sermons and states that "it was a fortunate sin that Adam sinned and his descendants; therefore as a result of this the world was made better." [1] In the 18th century, in the appendix to his Theodicy, Leibniz answers the objection that he who does not choose the best course must lack either power, knowledge, or goodness, and in doing so he refers to the felix culpa.

The concept also occurs in Hebrew tradition in the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and is associated with God’s judgment. Although it is not a fall, the thinking goes that without their exile in the desert the Israelites would not have the joy of finding their promised land. With their suffering came the hope of victory and their life restored. [6]

In a literary context, the term felix culpa can describe how a series of unfortunate events will eventually lead to a happier outcome. The theological concept is one of the underlying themes of Cameron Reed's science fiction novel, The Fortunate Fall ; the novel's title derives explicitly from the Latin phrase. It is also the theme of the fifteenth-century English text Adam lay ybounden, of unknown authorship, and it is used in various guises, such as "Foenix culprit", "Poor Felix Culapert!" and "phaymix cupplerts" by James Joyce in Finnegans Wake . John Milton includes the concept in Paradise Lost. In book 12, Adam proclaims that the good resulting from the Fall is "more wonderful" than the goodness in creation. He exclaims:

O goodness infinite, Goodness immense!

That all this good of evil shall produce,

And evil turn to good; more wonderful

Than that which creation first brought forth

Light out of Darkness! [...] [9]

In Robert Frost’s poem “Unharvested,” the narrator is attracted to a “scent of ripeness from over a wall” and finds an apple tree that has dropped all its apples to the ground: “there had been an apple fall/ As complete as the apple had given man.” Reveling in the scent and beauty of the fallen apples, the narrator proclaims, “May something go always unharvested!/ May much stay out of our stated plan…”

Original sin in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image of God. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3, and in texts such as Psalm 51:5 and Romans 5:12–21.

The problem of evil is the philosophical question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God. There are currently differing definitions of these concepts. The best known presentation of the problem is attributed to the Greek philosopher Epicurus. It was popularized by David Hume.

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all power and all goodness are simultaneously ascribed to God.

Total depravity is a Protestant theological doctrine derived from the concept of original sin. It teaches that, as a consequence of the Fall, every person born into the world is enslaved to the service of sin as a result of their fallen nature and, apart from the efficacious (irresistible) or prevenient (enabling) grace of God, is completely unable to choose by themselves to follow God, refrain from evil, or accept the gift of salvation as it is offered.

In Christianity and Judaism, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is one of two specific trees in the story of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2–3, along with the tree of life. Alternatively, some scholars have argued that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is just another name for the tree of life.

In classical theistic and monotheistic theology, the doctrine of divine simplicity says that God is simple . God exists as one unified entity, with no distinct attributes; God's existence is identical to God's essence.

Omnibenevolence is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "unlimited or infinite benevolence". Some philosophers, such as Epicurus, have argued that it is impossible, or at least improbable, for a deity to exhibit such a property alongside omniscience and omnipotence, as a result of the problem of evil. However, some philosophers, such as Alvin Plantinga, argue the plausibility of co-existence.

The fall of man, the fall of Adam, or simply the Fall, is a term used in Christianity to describe the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience. The doctrine of the Fall comes from a biblical interpretation of Genesis, chapters 1–3. At first, Adam and Eve lived with God in the Garden of Eden, but the serpent tempted them into eating the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, which God had forbidden. After doing so, they became ashamed of their nakedness and God expelled them from the Garden to prevent them from eating the fruit of the tree of life and becoming immortal.

Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal, more simply known as Théodicée, is a book of philosophy by the German polymath Gottfried Leibniz. The book, published in 1710, introduced the term theodicy, and its optimistic approach to the problem of evil is thought to have inspired Voltaire's Candide. Much of the work consists of a response to the ideas of the French philosopher Pierre Bayle and based on the author's conversation with Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, with whom Leibniz carried on a debate for many years.

The phrase "the best of all possible worlds" was coined by the German polymath and Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 work Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal, more commonly known simply as the Theodicy. The claim that the actual world is the best of all possible worlds is the central argument in Leibniz's theodicy, or his attempt to solve the problem of evil.

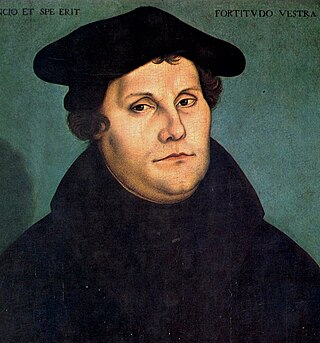

The theology of the Cross or staurology is a term coined by the German theologian Martin Luther to refer to theology that posits "the cross" as the only source of knowledge concerning who God is and how God saves. It is contrasted with the "theology of glory", which places greater emphasis on human abilities and human reason.

Eastern Orthodox theology is the theology particular to the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is characterized by monotheistic Trinitarianism, belief in the Incarnation of the divine Logos or only-begotten Son of God, cataphatic theology with apophatic theology, a hermeneutic defined by a Sacred Tradition, a catholic ecclesiology, a theology of the person, and a principally recapitulative and therapeutic soteriology.

The Irenaean theodicy is a Christian theodicy. It defends the probability of an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God in the face of evidence of evil in the world. Numerous variations of theodicy have been proposed which all maintain that, while evil exists, God is either not responsible for creating evil, or he is not guilty for creating evil. Typically, the Irenaean theodicy asserts that the world is the best of all possible worlds because it allows humans to fully develop. Most versions of the Irenaean theodicy propose that creation is incomplete, as humans are not yet fully developed, and experiencing evil and suffering is necessary for such development.

Alvin Plantinga's free-will defense is a logical argument developed by the American analytic philosopher Alvin Plantinga and published in its final version in his 1977 book God, Freedom, and Evil. Plantinga's argument is a defense against the logical problem of evil as formulated by the philosopher J. L. Mackie beginning in 1955. Mackie's formulation of the logical problem of evil argued that three attributes ascribed to God are logically incompatible with the existence of evil.

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exegesis, rational analysis and argument. Theologians may undertake the study of Christian theology for a variety of reasons, such as in order to:

The Augustinian theodicy, named for the 4th- and 5th-century theologian and philosopher Augustine of Hippo, is a type of Christian theodicy that developed in response to the evidential problem of evil. As such, it attempts to explain the probability of an omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-loving) God amid evidence of evil in the world. A number of variations of this kind of theodicy have been proposed throughout history; their similarities were first described by the 20th-century philosopher John Hick, who classified them as "Augustinian". They typically assert that God is perfectly (ideally) good, that he created the world out of nothing, and that evil is the result of humanity's original sin. The entry of evil into the world is generally explained as consequence of original sin and its continued presence due to humans' misuse of free will and concupiscence. God's goodness and benevolence, according to the Augustinian theodicy, remain perfect and without responsibility for evil or suffering.

Relating theodicy and the Bible is crucial to understanding Abrahamic theodicy because the Bible "has been, both in theory and in fact, the dominant influence upon ideas about God and evil in the Western world". Theodicy, in its most common form, is the attempt to answer the question of why a good God permits the manifestation of evil. Theodicy attempts to resolve the evidential problem of evil by reconciling the traditional divine characteristics of omnibenevolence and omnipotence, in either their absolute or relative form, with the occurrence of evil or suffering in the world.

Theistic finitism, also known as finitistic theism or finite godism, is the belief in a deity that is limited. It has been proposed by some philosophers and theologians to solve the problem of evil. Most finitists accept the absolute goodness of God but reject omnipotence.

Religious responses to the problem of evil are concerned with reconciling the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God. The problem of evil is acute for monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Judaism whose religion is based on such a God. But the question of "why does evil exist?" has also been studied in religions that are non-theistic or polytheistic, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism.

Evolutionary theodicies are responses to the question of animal suffering as an aspect of the problem of evil. These theodicies assert that a universe which contains the beauty and complexity this one does could only come about by the natural processes of evolution. If evolution is the only way this world could have been created, then the goodness of creation is intrinsically linked to the pain and evil of the evolutionary processes.

{{cite book}}: |website= ignored (help)