Ann Macbeth was a British embroiderer, designer, teacher and author, a member of the Glasgow Movement and an associate of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. She was also an active suffragette and designed banners for suffragists and suffragettes movements.

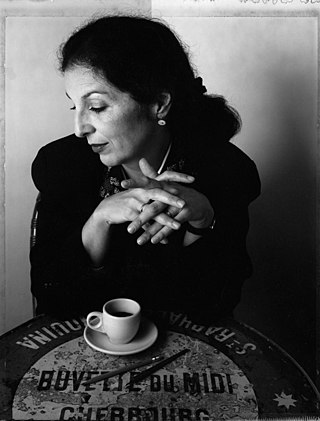

Eva Striker Zeisel was a Hungarian-born American industrial designer known for her work with ceramics, primarily from the period after she immigrated to the United States. Her forms are often abstractions of the natural world and human relationships. Work from throughout her prodigious career is included in important museum collections across the world. Zeisel declared herself a "maker of useful things."

Florence Marguerite Knoll Bassett was an American architect, interior designer, furniture designer, and entrepreneur who has been credited with revolutionizing office design and bringing modernist design to office interiors. Knoll and her husband, Hans Knoll, built Knoll Associates into a leader in the fields of furniture and interior design. She worked to professionalize the field of interior design, fighting against gendered stereotypes of the decorator. She is known for her open office designs, populated with modernist furniture and organized rationally for the needs of office workers. Her modernist aesthetic was known for clean lines and clear geometries that were humanized with textures, organic shapes, and colour.

Candace Wheeler, traditionally credited as the mother of interior design, was one of America's first woman interior and textile designers. She helped open the field of interior design to women, supported craftswomen, and promoted American design reform. A committed feminist, she intentionally employed women and encouraged their education, especially in the fine and applied arts, and fostered home industries for rural women. She also did editorial work and wrote several books and many articles, encompassing fiction, semi-fiction and non-fiction, for adults and children. She used her exceptional organizational skills to co-found both the Society of Decorative Art in New York City (1877) and the New York Exchange for Women's Work (1878); and she partnered with Louis Comfort Tiffany and others in designing interiors, specializing in textiles (1879-1883), then founded her own firm, The Associated Artists (1883-1907).

Muriel Cooper was a pioneering book designer, digital designer, researcher, and educator. She was the first design director of the MIT Press, instilling a Bauhaus-influenced design style into its many publications. She moved on to become founder of MIT's Visible Language Workshop, and later became a co-founder of the MIT Media Lab. In 2007, a New York Times article called her "the design heroine you've probably never heard of".

Marie Daugherty Webster was a quilt designer, quilt producer, and businesswoman, as well as a lecturer and author of Quilts, Their Story, and How to Make Them (1915), the first American book about the history of quilting, reprinted many times since. She also ran the Practical Patchwork Company, a quilt pattern-making business from her home in Wabash, Indiana, for more than thirty years. Webster's appliquéd quilts influenced modern quilting designs of the early twentieth century. Her quilts have been featured in museums and gallery exhibition in the United States and Japan. The Indianapolis Museum of Art holds the largest collection of her quilts in the United States. Webster was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame in 1991. The Marie Webster House, her former residence in Marion, Indiana, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993, and serves as the present-day home of the Quilters Hall of Fame.

Vera Huppe Maxwell was an American pioneering sportswear and fashion designer.

Bernardo Sandals was founded in 1946 by architect Bernard Rudofsky and Berta Rudofsky. The Rudofskys went into sandal design following the 1944 exhibition, "Are Clothes Modern?" that Mr. Rudofsky curated at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Alice Cordelia Morse was an American designer of book covers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Her work was inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, and she is often placed as one of the top three book designers of her day.

Elizabeth Hawes was an American clothing designer, outspoken critic of the fashion industry, and champion of ready to wear and people's right to have the clothes they desired, rather than the clothes dictated to be fashionable, an idea encapsulated in her book Fashion Is Spinach, published in 1938. She was among the first American apparel designers to establish their reputations outside of Paris haute couture. In addition to her work in the fashion industry as a sketcher, copyist, stylist, and journalist, and designer, she was an author, union organizer, champion of gender equality, and political activist.

Clare Potter was a fashion designer who was born in Jersey City, New Jersey in 1903. In the 1930s she was one of the first American fashion designers to be promoted as an individual design talent. Working under her elided name Clarepotter, she has been credited as one of the inventors of American sportswear. Based in Manhattan, she continued designing through the 1940s and 1950s. Her clothes were renowned for being elegant, but easy-to-wear and relaxed, and for their distinctive use of colour. She founded a ready-to-wear fashion company in Manhattan named Timbertop in 1948, and in the 1960s she also established a wholesale company to manufacture fashions. Potter was one of the 17 women gathered together by Edna Woolman Chase, editor-in-chief of Vogue to form the Fashion Group International, Inc., in 1928.

Dorothy Wright Liebes was an American textile designer and weaver renowned for her innovative, custom-designed modern fabrics for architects and interior designers. She was known as "the mother of modern weaving".

Louise Fili is an American graphic designer recognized for use of typography and quality design. Her work often draws inspiration from her love of Italy, Modernism, and European Art Deco styles. Considered a leader in the postmodern return to historical styles in book jacket design, Fili explores historic typography combined with modern colors and compositions.

Ilonka Karasz, was a Hungarian-American designer and illustrator known for avant-garde industrial design and for her many New Yorker magazine covers.

Eszter Haraszty was a Hungarian-born designer best known for her work as head of the textiles department at Knoll.

Mary Adaline Edwarda Carter was an American industrial art instructor and designer from the U.S. state of Vermont.

School of Industrial Art and Technical Design for Women was an American school of industrial design founded in 1881 and located in New York City. Pupils were made familiar with the practicality of design, with the workings of machinery, and the technicalities of design as applied to various industries. In its day, it was said to be the only school of practical design for industrial manufacture in the world.

Ella Seaver Owen was an American artist and teacher. For many years, she taught oil, watercolor, and china painting, and was one of the pioneers, outside of New York City, in china firing. Owen was one of the first women admitted to the University of Vermont, and was one of the founders of the Alpha Rho out of which grew Lambda of Kappa Alpha Theta.

Sarah A. Worden was an American painter of landscapes and portraits. She was also an art instructor in various schools and for several years, at Mount Holyoke College.

Lenox Hall was a non-sectarian resident and day school for girls and young women in St. Louis, Missouri. Located on Taylor and McPherson, it was situated four blocks west of Limit Walk, the western boundary of the city of St. Louis. It was established by M. Louise Thomas, the principal, in September 1907. In 1910, the architects of the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis, Barnett, Haynes & Barnett, were chosen to design the new Lenox Hall, in University City, Missouri, early English in type.