Edward VI was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his third wife, Jane Seymour, Edward was the first English monarch to be raised as a Protestant. During his reign, the realm was governed by a regency council because Edward never reached maturity. The council was first led by his uncle Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (1547–1549), and then by John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland (1550–1553).

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, which was one of the causes of the separation of the English Church from union with the Holy See. Along with Thomas Cromwell, he supported the principle of royal supremacy, in which the king was considered sovereign over the Church within his realm.

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation, was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Towards the end of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism and in turn resulted in a major schism within Western Christianity.

Thomas Cromwell, briefly Earl of Essex, was an English statesman and lawyer who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charges for the execution.

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, finalised in 1571, are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the English Reformation. The Thirty-nine Articles form part of the Book of Common Prayer used by the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion, as well as by denominations outside of the Anglican Communion that identify with the Anglican tradition.

Nicholas Ridley was an English Bishop of London. Ridley was one of the Oxford Martyrs burned at the stake during the Marian Persecutions, for his teachings and his support of Lady Jane Grey. He is remembered with a commemoration in the calendar of saints in some parts of the Anglican Communion on 16 October.

The Exhortation and Litany, published in 1544, is the earliest officially authorized vernacular service in English. The same rite survives, in modified form, in the Book of Common Prayer.

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Reformation. It permanently shaped the Church of England's doctrine and liturgy, laying the foundation for the unique identity of Anglicanism.

John Stokesley was an English clergyman who was Bishop of London during the reign of Henry VIII.

Via media is a Latin phrase meaning "the middle road" or the "way between two extremes".

The history of the Anglican Communion may be attributed mainly to the worldwide spread of British culture associated with the British Empire. Among other things the Church of England spread around the world and, gradually developing autonomy in each region of the world, became the communion as it exists today.

John Ponet, sometimes spelled John Poynet, was an English Protestant churchman and controversial writer, the bishop of Winchester and Marian exile. He is now best known as a resistance theorist who made a sustained attack on the divine right of kings.

Anglican doctrine is the body of Christian teachings used to guide the religious and moral practices of Anglicanism.

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England was forced by its monarchs and elites to break away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Reformation, a religious and political movement that affected the practice of Christianity in Western and Central Europe.

Henry Cole was a senior English Roman Catholic churchman and academic.

Receptionism is a form of Anglican eucharistic theology which teaches that during the Eucharist the bread and wine remain unchanged after the consecration, but when communicants receive the bread and wine, they also receive the body and blood of Christ by faith. It was a common view among Anglicans in the 16th and 17th centuries, and prominent theologians who subscribed to this doctrine were Thomas Cranmer and Richard Hooker.

In 16th-century Christianity, Protestantism came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian world.

Sir John Gostwick was an English courtier, administrator and MP.

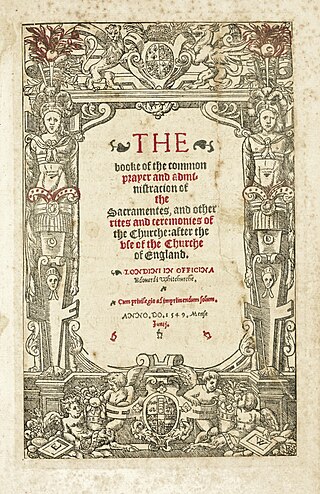

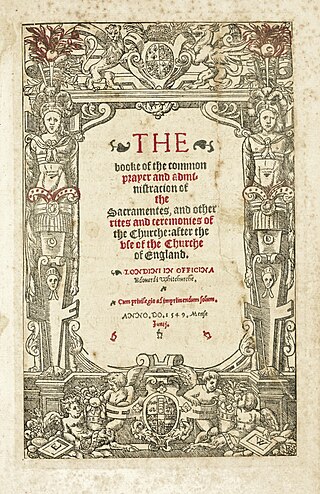

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the original version of the Book of Common Prayer, variations of which are still in use as the official liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican churches. Written during the English Reformation, the prayer book was largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, who borrowed from a large number of other sources. Evidence of Cranmer's Protestant theology can be seen throughout the book; however, the services maintain the traditional forms and sacramental language inherited from medieval Catholic liturgies. Criticised by Protestants for being too traditional, it was replaced by the significantly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer.

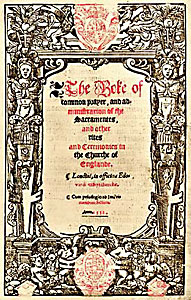

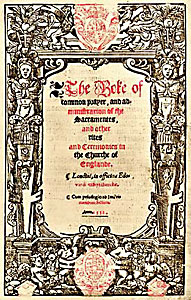

The 1552 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI, was the second version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) and contained the official liturgy of the Church of England from November 1552 until July 1553. The first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549 as part of the English Reformation, but Protestants criticised it for being too similar to traditional Roman Catholic services. The 1552 prayer book was revised to be explicitly Reformed in its theology.