Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the largest branches of Christianity, with around 110 million adherents worldwide as of 2001.

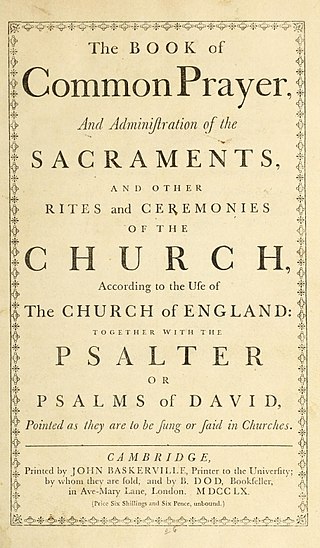

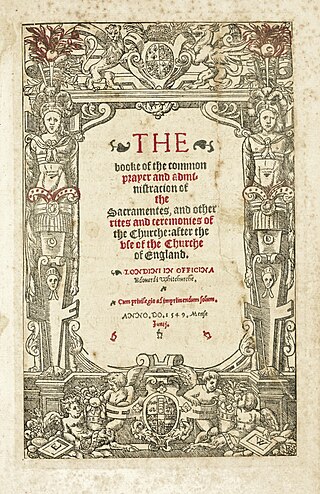

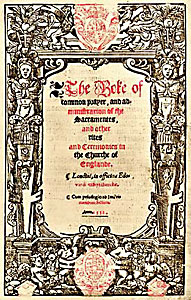

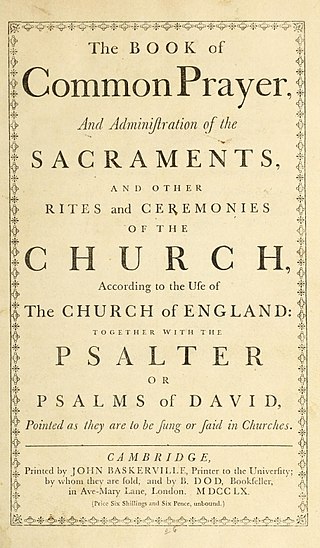

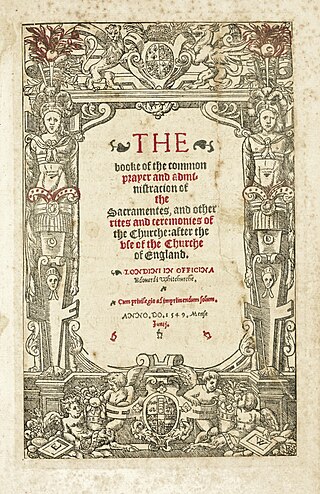

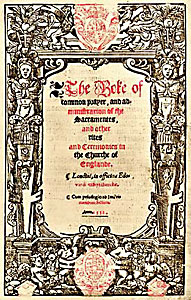

The Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The first prayer book, published in 1549 in the reign of King Edward VI of England, was a product of the English Reformation following the break with Rome. The work of 1549 was the first prayer book to include the complete forms of service for daily and Sunday worship in English. It contained Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, the Litany, and Holy Communion and also the occasional services in full: the orders for Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, "prayers to be said with the sick", and a funeral service. It also set out in full the "propers" : the introits, collects, and epistle and gospel readings for the Sunday service of Holy Communion. Old Testament and New Testament readings for daily prayer were specified in tabular format as were the Psalms and canticles, mostly biblical, that were provided to be said or sung between the readings.

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, which was one of the causes of the separation of the English Church from union with the Holy See. Along with Thomas Cromwell, he supported the principle of royal supremacy, in which the king was considered sovereign over the Church within his realm.

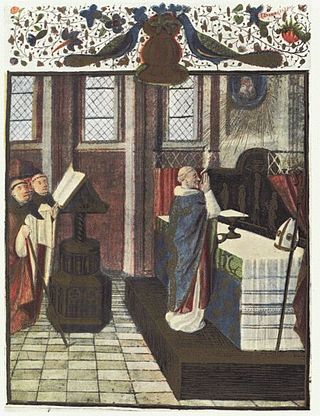

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term Mass is commonly used in the Catholic Church, Western Rite Orthodoxy, Old Catholicism, and Independent Catholicism. The term is also used in some Lutheran churches, as well as in some Anglican churches, and on rare occasion by other Protestant churches.

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, finalised in 1571, are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the English Reformation. The Thirty-nine Articles form part of the Book of Common Prayer used by the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion, as well as by denominations outside of the Anglican Communion that identify with the Anglican tradition.

Matthew Parker was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 to his death. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder of a distinctive tradition of Anglican theological thought.

The Exhortation and Litany, published in 1544, is the earliest officially authorized vernacular service in English. The same rite survives, in modified form, in the Book of Common Prayer.

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Reformation. It permanently shaped the Church of England's doctrine and liturgy, laying the foundation for the unique identity of Anglicanism.

John Jewel of Devon, England was Bishop of Salisbury from 1559 to 1571.

Nicholas Shaxton was Bishop of Salisbury. For a time, he had been a Reformer, but recanted this position, returning to the Roman faith. Under Henry VIII, he attempted to persuade other Protestant leaders to also recant. Under Mary I, he took part in several heresy trials of those who became Protestant martyrs.

Anglican eucharistic theology is diverse in practice, reflecting the comprehensiveness of Anglicanism. Its sources include prayer book rubrics, writings on sacramental theology by Anglican divines, and the regulations and orientations of ecclesiastical provinces. The principal source material is the Book of Common Prayer, specifically its eucharistic prayers and Article XXVIII of the Thirty-Nine Articles. Article XXVIII comprises the foundational Anglican doctrinal statement about the Eucharist, although its interpretation varies among churches of the Anglican Communion and in different traditions of churchmanship such as Anglo-Catholicism and Evangelical Anglicanism.

Lex orandi, lex credendi, sometimes expanded as Lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi, is a motto in Christian tradition, which means that prayer and belief are integral to each other and that liturgy is not distinct from theology. It refers to the relationship between worship and belief. As an ancient Christian principle it provided a measure for developing the ancient Christian creeds, the canon of scripture, and other doctrinal matters. It is based on the prayer texts of the Church, that is, the Church's liturgy. In the Early Church, there was liturgical tradition before there was a common creed, and before there was an officially sanctioned biblical canon. These liturgical traditions provided the theological framework for establishing the creeds and canon.

A homiliarium or homiliary is a collection of homilies, or familiar explanations of the Gospels.

Anglican doctrine is the body of Christian teachings used to guide the religious and moral practices of Anglicans.

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England was forced by its monarchs and elites to break away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Reformation, a religious and political movement that affected the practice of Christianity in Western and Central Europe.

Thomas Bennet (1673–1728) was an English clergyman, known for controversial and polemical writings, and as a Hebraist.

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the original version of the Book of Common Prayer, variations of which are still in use as the official liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican churches. Written during the English Reformation, the prayer book was largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, who borrowed from a large number of other sources. Evidence of Cranmer's Protestant theology can be seen throughout the book; however, the services maintain the traditional forms and sacramental language inherited from medieval Catholic liturgies. Criticised by Protestants for being too traditional, it was replaced by the significantly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer.

The 1552 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI, was the second version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) and contained the official liturgy of the Church of England from November 1552 until July 1553. The first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549 as part of the English Reformation, but Protestants criticised it for being too similar to traditional Roman Catholic services. The 1552 prayer book was revised to be explicitly Reformed in its theology.

The Forty-two Articles were the official doctrinal statement of the Church of England for a brief period in 1553. Written by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and published by King Edward VI's privy council along with a requirement for clergy to subscribe to it, it represented the height of official church reformation prior to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. It staked out a position among Protestant movements of the day, opposing Anabaptist claims and disagreeing with Zwinglian positions without taking an explicitly Calvinist or Lutheran approach.

John Oswen was an English printer.