A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanical stress, the impact and penetration of pressure-driven projectiles, pressure damage, and explosion-generated effects. Bombs have been utilized since the 11th century starting in East Asia.

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in the United Kingdom since 1889 to replace black powder as a military propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burning rates and consequently low brisance. These produce a subsonic deflagration wave rather than the supersonic detonation wave produced by brisants, or high explosives. The hot gases produced by burning gunpowder or cordite generate sufficient pressure to propel a bullet or shell to its target, but not so quickly as to routinely destroy the barrel of the gun.

An autocannon, automatic cannon or machine cannon is a fully automatic gun that is capable of rapid-firing large-caliber armour-piercing, explosive or incendiary shells, as opposed to the smaller-caliber kinetic projectiles (bullets) fired by a machine gun. Autocannons have a longer effective range and greater terminal performance than machine guns, due to the use of larger/heavier munitions, but are usually smaller than tank guns, howitzers, field guns or other artillery. When used on its own, the word "autocannon" typically indicates a non-rotary weapon with a single barrel. When multiple rotating barrels are involved, such a weapon is referred to as a "rotary autocannon" or occasionally "rotary cannon", for short.

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first developed anti-tank weapon was a scaled-up bolt-action rifle, the Mauser 1918 T-Gewehr, that fired a 13.2mm cartridge with a solid bullet that could penetrate the thin armor of tanks of the time and destroy the engine or ricochet inside, killing occupants. Because tanks represent an enemy's strong force projection on land, military strategists have incorporated anti-tank warfare into the doctrine of nearly every combat service since. The most predominant anti-tank weapons at the start of World War II in 1939 included the tank-mounted gun, anti-tank guns and anti-tank grenades used by the infantry, and ground-attack aircraft.

Technology during World War I (1914–1918) reflected a trend toward industrialism and the application of mass-production methods to weapons and to the technology of warfare in general. This trend began at least fifty years prior to World War I during the American Civil War of 1861–1865, and continued through many smaller conflicts in which soldiers and strategists tested new weapons.

Technology played a significant role in World War II. Some of the technologies used during the war were developed during the interwar years of the 1920s and 1930s, much was developed in response to needs and lessons learned during the war, while others were beginning to be developed as the war ended. Many wars had major effects on the technologies that we use in our daily lives. However, compared to previous wars, World War II had the greatest effect on the technology and devices that are used today. Technology also played a greater role in the conduct of World War II than in any other war in history, and had a critical role in its outcome.

A shell, in a military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. Modern usage sometimes includes large solid kinetic projectiles, which are more properly termed shot. Solid shot may contain a pyrotechnic compound if a tracer or spotting charge is used.

"Mills bomb" is the popular name for a series of British hand grenades which were designed by William Mills. They were the first modern fragmentation grenades used by the British Army and saw widespread use in the First and Second World Wars.

Stielhandgranate is the German term for "stick hand grenade" and generally refers to a prominent series of World War I and World War II-era German stick grenade designs, distinguished by their long wooden handles, pull cord arming and cylindrical warheads. The first models were introduced by the Imperial German Army during World War I and the final design was introduced during World War II by the German Wehrmacht.

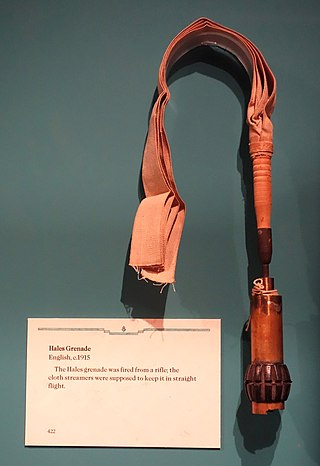

A rifle grenade is a grenade that uses a rifle-based launcher to permit a longer effective range than would be possible if the grenade were thrown by hand.

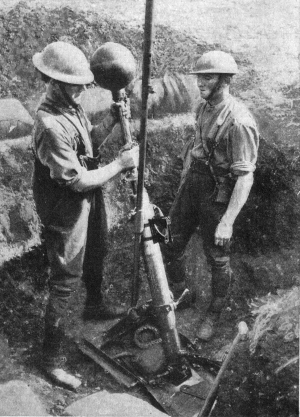

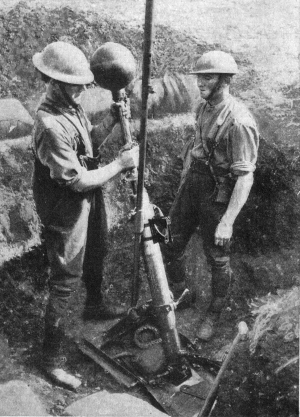

The Stokes mortar was a British trench mortar designed by Sir Wilfred Stokes KBE that was issued to the British and U.S. armies, as well as the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps, during the latter half of the First World War. The 3-inch trench mortar is a smooth-bore, muzzle-loading weapon for high angles of fire. Although it is called a 3-inch mortar, its bore is actually 3.2 inches or 81 mm.

The Newton 6-inch mortar was the standard British medium mortar in World War I from early 1917 onwards.

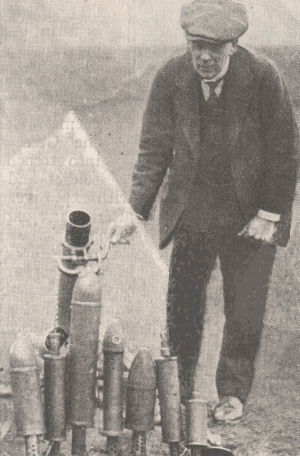

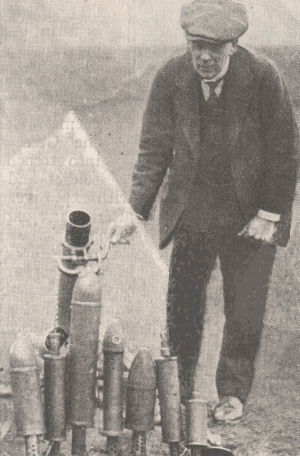

The 2 inch medium trench mortar, also known as the 2-inch howitzer, and nicknamed the "toffee apple" or "plum pudding" mortar, was a British smooth bore muzzle loading (SBML) medium trench mortar in use in World War I from mid-1915 to mid-1917. The designation "2-inch" refers to the mortar barrel, into which only the 22-inch bomb shaft but not the bomb itself was inserted; the spherical bomb itself was actually 9 inches (230 mm) in diameter and weighed 42 lb (19 kg), hence this weapon is more comparable to a standard mortar of approximately 5-6 inch bore.

The Mortier de 58 mm type 2 or Mortier de 58 mm T N°2, also known as the Crapouillot or "little toad" from its appearance, was the standard French medium trench mortar of World War I.

William Howard Livens, was an engineer, a soldier in the British Army and an inventor particularly known for the design of chemical warfare and flame warfare weapons. Resourceful and clever, Livens' successful creations were characterised by being very practical and easy to produce in large numbers. In an obituary, Sir Harold Hartley said "Livens combined great energy and enterprise with a flair for seeing simple solutions and inventive genius."

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand, but can also refer to a shell shot from the muzzle of a rifle or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade generally consists of an explosive charge ("filler"), a detonator mechanism, an internal striker to trigger the detonator, and a safety lever secured by a cotter pin. The user removes the safety pin before throwing, and once the grenade leaves the hand the safety lever gets released, allowing the striker to trigger a primer that ignites a fuze, which burns down to the detonator and explodes the main charge.

The British Army used a variety of standardized battle uniforms and weapons during World War I. According to the British official historian Brigadier James E. Edmonds writing in 1925, "The British Army of 1914 was the best trained best equipped and best organized British Army ever sent to war". They were the only army to wear any form of a camouflage uniform; the value of drab clothing was quickly recognised by the British Army, who introduced Khaki drill for Indian and colonial warfare from the mid-19th century on. As part of a series of reforms following the Second Boer War, a darker khaki serge was adopted in 1902, for service dress in Britain itself. The British military authorities showed more foresight than their French counterparts, who retained highly visible blue coats and red trousers for active service until the final units received a new uniform over a year into World War I. The soldier was issued with the 1908 Pattern Webbing for carrying personal equipment, and he was armed with the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield rifle.

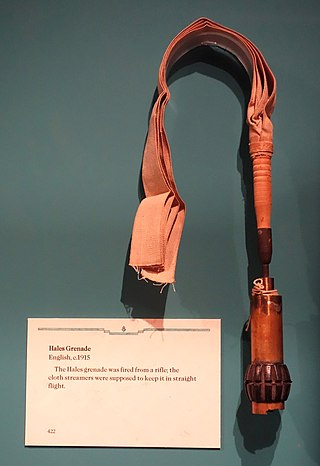

The Hales rifle grenade is the name for several rifle grenades used by British forces during World War I. All of these are based on the No. 3 design.

The No. 2 grenade is a percussion cap fragmentation and rifle grenade used by the United Kingdom during World War I.

The kleineGranatenwerfer 16 or Gr.W.16(Small Grenade Launcher Model 1916) in English, was an infantry mortar used by the Central Powers during the First World War. It was designed by a Hungarian priest named Father Vécer and was first used by the Austro-Hungarian Army in 1915. In Austro-Hungarian service, they received the nickname "Priesterwerfers". In 1916 Germany began producing a modified version under license for the Imperial German Army.