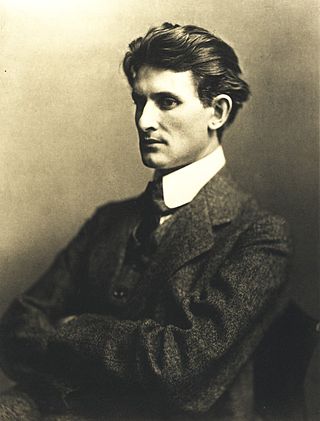

Friedrich Wilhelm Wolters (2 September 1876, Uerdingen - 14 April 1930. Munich) was a German historian, poet and translator; one of the central figures in the George-Kreis.

Friedrich Wilhelm Wolters (2 September 1876, Uerdingen - 14 April 1930. Munich) was a German historian, poet and translator; one of the central figures in the George-Kreis.

He was the son of Friedrich Wolters, a businessman, and received his primary education in Rheydt and graduated from a gymnasium in Munich. In 1891, he began studying history, linguistics and philosophy at the University of Freiburg but, after one semester, returned to Munich. From 1899, he studied history and economics at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, with Kurt Breysig and Gustav von Schmoller. In 1900, he spent some time in Paris, attending lectures at the Sorbonne. [1] He received his Doctorate in 1903. Two years later, he published an expanded version of his dissertation.

From 1907 to 1908, he served as one of the private instructors to Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia, who was struggling to complete his Doctorate. It is believed that Wolters wrote the Prince's dissertation himself. It was accepted "summa cum laude". Wolters received a few hundred Reichsmarks and was awarded the Order of the Crown, 4th class. [2] After that, he earned his living as a teacher; primarily at girls' schools.

In 1909, after many years of trying to meet the poet Stefan George, whom he greatly admired, he finally attracted his attention with a pamphlet called Herrschaft und Dienst (Leadership and Service). Excerpts were published in George's magazine, Blätter für die Kunst . Wolters description of an ideal ruler and his society was specifically designed to flatter George. [3] Shortly after, they spent a few weeks together in Berlin. The following year, he was accepted into George's inner circle, as someone who could broaden his image among German youth.

For this purpose, he published a new journal, the Jahrbuch für die geistige Bewegung (Yearbook for the Spiritual Movement), edited by Friedrich Gundolf. It included several major contributions by Wolters. For the first volume, he proposed dividing the human mind into "creative" and "ordering" forces, which are in opposition.0 [4] In the next volume, he expanded on the concept of "gestalt" and its relationship to holism. [5] In volume three, he extended his concepts to their external state, calling upon youth to take responsibility for the renewal of society. His proposals rejected the idea of equality, in favor of a natural hierarchy, under the benevolent control of a charismatic leader. [6]

Wolters commitment to George was unconditional, and he would beg permission from "The Master" before undertaking any action, however simple. His reverence reached the point where other members of the Circle referred to him as "St. Paul", and friends from his earlier days were appalled by what they considered to be a "hideous transformation". [7] Although George greatly appreciated Wolter's contributions to his movement, these strong feelings were not returned. In fact, many of George's followers were uncomfortable with this degree of adoration, so Wolters essentially ended by creating his own "Circle". [8]

In 1914, after a year of studying, he passed the habilitation exam and became a private lecturer at the University. Shortly after, World War I broke out. He served as a driver and courier in several places, on both fronts, but never saw combat, although he did witness some events of the Serbian campaign. In his letters, he glorified the conflict and spoke of the spiritual feelings aroused by the war of attrition. [9] In 1915, while on leave, he married Erika Schwartzkopff, who he had met at the home of his former instructor, Breysig; also a member of the Circle.

In 1920, he was appointed Professor of History at the University of Marburg, where he sought talented young men to join the Circle; making a significant impression on many. Some admired him, but rejected George. His students included Hans-Georg Gadamer, Herman Schmalenbach, Roland Hampe and Adolf Reichwein. George stayed with Wolters for several weeks every year. In 1924, he received another professorship, at the University of Kiel. He owed that appointment to Carl Heinrich Becker, State Secretary at the Ministry of Education, who used his influence to promote members of the Circle. Once again, George was a regular visitor.

His wife, Erika, died in 1925. By this time, he had virtually abandoned history for nationalist propaganda. [9] He also became involved in issues of racial purity, and was a major contributor to encouraging belief in what was called "Die schwarze Schmach" (The Black Disgrace). [10] His position was somewhere between the German National People's Party (DNVP) and the German People's Party (DVP). He once took part in a völkisch memorial service for the right-wing martyr, Albert Leo Schlageter. George, who disliked common politics, became increasingly skeptical of Wolters' ideas and motives. [11]

In 1927 he remarried, to Gemma Thiersch (1907-1994), daughter of the architect Paul Thiersch. Two years later, he published what he considered to be his "magnum opus": Stefan George und die Blätter für die Kunst. Deutsche Geistesgeschichte seit 1890 (Stefan George and the Leaves of Art: German intellectual history since 1890). The critical reception was mixed. Even Friedrich Gundolf, one of George's early followers, thought it was a " hopelessly bad, thoroughly mendacious book". [9] There were also anti-Semitic undertones that led Jewish members of the Circle, such as Karl Wolfskehl, to express their resentment. [12]

He had suffered from heart problems since being hospitalized for severe rheumatism in 1917, during the war. While visiting Munich in 1930, he became ill and was diagnosed with an arterial thrombosis. After showing some improvement, he died suddenly, a month later, and was interred at the Waldfriedhof. [9] His friends, Julius Landmann and Carl Petersen created the Friedrich Wolters Foundation; supported with funds from the University of Kiel. After Landmann's death, the Foundation became associated with the Nazis and his widow, Edith , called for its dissolution. It continued to operate until 1937, when its funding was withdrawn.

Karl Wolfskehl was a German Jewish author and translator. He wrote poetry, prose and drama in German, and translated from French, English, Italian, Hebrew, Latin and Old/Middle High German into German.

Stefan Anton George was a German symbolist poet and a translator of Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Hesiod, and Charles Baudelaire. He is also known for his role as leader of the highly influential literary circle called the George-Kreis and for founding the literary magazine Blätter für die Kunst. From the inception of his circle, George and his followers represented a literary and cultural revolt against the literary realism trend in German literature during the last decades of the German Empire.

Friedrich Gundolf, born Friedrich Leopold Gundelfinger was a German-Jewish literary scholar and poet and one of the best known academics of the Weimar Republic.

Gottfried Boehm is a German art historian and philosopher.

Maximilian Kronberger, known familiarly as Maximin, was a German poet and a significant figure in the literary circle of Stefan George.

Count Alexander von Stauffenberg was a German aristocrat and historian. His twin brother Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg and younger brother Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg were among the leaders of the 20 July Plot against Hitler in 1944.

Ludwig Benjamin Derleth was a German writer and poet, best known for his highly-stylized and anti-humanistic writings on spirituality and Christianity.

The George-Kreis was an influential German literary group centred on the charismatic author Stefan George. Formed in the late 19th century, when George published a new literary magazine called Blätter für die Kunst, the group featured many highly regarded writers and academics. In addition to sharing cultural interests, the circle reflected mystical and political themes within the sphere of the Conservative Revolutionary movement. The group disbanded when George died in December 1933.

Arthur Salz was a German professor of sociology and economics who wrote on mercantilism, imperialism, and power. He taught at the University of Heidelberg before being forced to flee Germany because of his Jewish faith. He was familiar with the Stefan George circle and married Sophie Kantorowiz, the sister of historian Ernst Kantorowicz.

Hans Jantzen was a German art historian who specialized in Medieval art.

Theodor Zacharias Friedrich Alt was a German painter.

Friedrich Wilhelm Karl Ritter von Hegel was a German historian and son of the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. During his lifetime he was a well-known and well-reputed historian who received many awards and honours. He was one of the major urban historians during the second half of the 19th century.

The Belgradstraße is a 2.0-kilometer-long street in Munich's Schwabing district. It runs in a south–north direction between Kurfürstenplatz and Petuelpark, where it merges into Knorrstraße. The street was named after the Serbian capital Belgrade.

Adolph Kohut was a German-Hungarian journalist, literature and cultural historian, biographer, recitator and translator from Hungarian origin.

Friedrich Lienhard was a German writer and nationalist ideologue.

Wolfgang Schultz was an Austrian philosopher who served as Professor and Chair of Philosophy at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Paul Thiersch was a German architect and designer.

Ernst August Bertram was a German professor of German studies at the University of Cologne, but also a poet and writer who was close to the George-Kreis and the lyricist Stefan George.

Saladin Schmitt, real name Joseph Anton Schmitt, also active under the pseudonym Harald Hoffmann) was a German theatre director.

Adolf Friedrich Rutenberg was a German geography teacher, Young Hegelian and journalist. He was a close friend of German philosophers Karl Marx and Max Stirner. He was alongside Bruno Bauer as one of two reported mourners at Stirner's graveside.