Anza-Borrego Desert State Park is a California State Park located within the Colorado Desert of southern California, United States. The park takes its name from 18th century Spanish explorer Juan Bautista de Anza and borrego, a Spanish word for sheep. With 585,930 acres (237,120 ha) that includes one-fifth of San Diego County, it is the largest state park in California and the third largest state park nationally.

The San Diego and Arizona Railway was a 148-mile (238 km) short line U.S. railroad founded by entrepreneur John D. Spreckels, and dubbed "The Impossible Railroad" by engineers of its day due to the immense logistical challenges involved. It linked San Diego, its western terminus, with El Centro, its eastern terminus, where passengers could connect with Southern Pacific's transcontinental lines, eliminating the need to first travel north via Los Angeles or Riverside.

The San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway Company is a short-line American railroad founded in 1906 as the San Diego and Arizona Railway (SD&A) by sugar magnate, developer, and entrepreneur John D. Spreckels. Dubbed "The Impossible Railroad" by many engineers of its day due to the immense logistical challenges involved, the line was established in part to provide San Diego with a direct rail link to the east by connecting with the Southern Pacific Railroad lines in El Centro, California.

The San Diego and Imperial Valley Railroad (SD&IV) is a class III railroad operating freight rail service in the San Diego area, providing service to customers in the region and moving railcars between the end of the BNSF Railway in Downtown San Diego and the Mexico–United States border in San Ysidro. The railroad has exclusive trackage rights to operate over tracks of the San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway, a subsidiary of the Metropolitan Transit System, the regional public transit service provider. Tracks are shared with the San Diego Trolley, another subsidiary of the Metropolitan Transit System, and freight trains are only operated at night when passenger service is not in operation. The San Diego & Imperial Valley Railroad was established in October 1984 and is owned and operated by Genesee & Wyoming, a holding company that operates more than 100 shortline railroads like the SD&IV.

Carrizo Gorge Railway, Inc. was a railroad operator on the San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway (SD&AE) from Tijuana, Mexico, to Plaster City, California.

The Fish Creek Mountains Wilderness is located about 25 miles west of Brawley, California, and southeast of the Vallecito Mountains in the United States. The wilderness is located in the Fish Creek Mountains region in the northern part of the Carrizo Impact Area, which is closed to the public.

The Carrizo Impact Area was used by the United States Navy as an air-to-ground bombing range during World War II and the Korean War. It is in the Anza-Borrego Desert in south central California and covers about 45 square miles (120 km2). The majority of the range is in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and about a third is owned by the United States Bureau of Land Management, including the Fish Creek Mountains Wilderness. The Navy currently only owns about 2 percent of the land and about 5 percent is privately owned. There are no structures or habitations within a 20-mile (32 km) radius of the site.

The Mud Caves are a popular feature in Anza Borrego Desert State Park in San Diego County, California. The caves, located in the Carrizo Badlands, along the Arroyo Tapiado, were created by water flowing through a thick deposit of silt and are an example of pseudokarst topography. There are at least 22 caves, some up to 1,000 feet (300 m) in length and 80 feet (24 m) in height. Many of the caves are easily accessed.

The Coyote Mountains are a small mountain range in San Diego and Imperial Counties in southern California. The Coyotes form a narrow ESE trending 2 mi (3.2 km) wide range with a length of about 12 mi (19 km). The southeast end turns and forms a 2 mi (3.2 km) north trending "hook". The highest point is Carrizo Mountain on the northeast end with an elevation of 2,408 feet (734 m). Mine Peak at the northwest end of the range has an elevation of 1,850 ft (560 m). Coyote Wash along I-8 along the southeast margin of the range is 100 to 300 feet in elevation. Plaster City lies in the Yuha Desert about 5.5 mi (8.9 km) east of the east end of the range.

The Sawtooth Mountains Wilderness is a federal wilderness area of 32,136 acres (130.0 km2) located in the Sawtooth Mountains in eastern San Diego County, California. It is located in the Colorado Desert, 35 miles (56 km) south of Borrego Springs, near Anza Borrego Desert State Park.

The Santa Rosa Wilderness is a 72,259-acre (292.42 km2) wilderness area in Southern California, in the Santa Rosa Mountains of Riverside and San Diego counties, California. It is in the Colorado Desert section of the Sonoran Desert, above the Coachella Valley and Lower Colorado River Valley regions in a Peninsular Range, between La Quinta to the north and Anza Borrego Desert State Park to the south. The United States Congress established the wilderness in 1984 with the passage of the California Wilderness Act, managed by both the US Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. In 2009, the Omnibus Public Land Management Act was signed into law which added more than 2,000 acres (8.1 km2). Most of the Santa Rosa Wilderness is within the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument.

The Butterfield Overland Mail in California was created by the United States Congress on March 3, 1857, and operated until June 30, 1861. Subsequently, other stage lines operated along the Butterfield Overland Mail in route in Alta California until the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in Yuma, Arizona in 1877.

Earthquake Valley is a desert valley east of Julian, California, which contains parts of the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. It is the location of the Shelter Valley Ranchos subdivision, which is also known as the unincorporated community of Shelter Valley. The official USGS place name for the geologic feature in which Shelter Valley is situated is "Earthquake Valley", and the 1959 USGS Topographic map makes no reference to Shelter Valley. The name of the unincorporated community Shelter Valley is typically used both locally and by the media to refer generally to the geological feature of Earthquake Valley, and it is common for both names to be referenced in publications after the 1962 establishment of the subdivision. Author, poet, artist and primitivist Marshal South lived in and wrote about the general area, in a series of articles for Desert Magazine between 1941 and 1948. A number of notable trails pass through the valley, including the Pacific Crest Trail, the California Riding and Hiking Trail, and the Southern Emigrant Trail.

Sunbelt Publications is an American publication company that was incorporated in 1988. The company publishes and distributes multi-language pictorials, natural science and outdoor guidebooks, and regional references. The company is located in El Cajon, California.

Palm Spring is a spring in Mesquite Oasis, a desert oasis amidst a mesquite thicket and a few palms, close to Carrizo Creek, within the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in San Diego County, California.

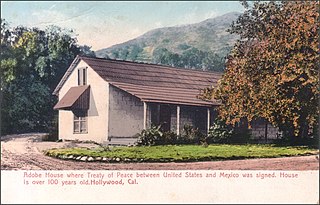

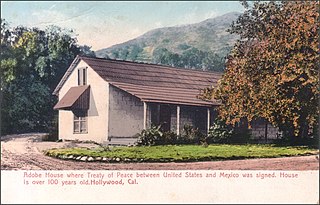

Carrizo Creek Station, a former stage station of the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line and Butterfield Overland Mail, located in Imperial County, California just east of the San Diego County line. It lies within the boundaries of the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park just west of the Carrizo Impact Area. Its site is located along the bank of Carrizo Creek.

San Felipe Creek is a stream in Imperial and San Diego Counties of California. It arises in the Volcan Mountains of San Diego County 33°11′57″N116°37′35″W, and runs eastward, gathering the waters of most of the eastern slope of the mountains and desert of the county in the San Sebastian Marsh before it empties into the Salton Sea. It is probably the last remaining perennial natural desert stream in the Colorado Desert region. In 1974, the San Felipe Creek Area was designated as a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service.

Clinton Gilbert Abbott was an American ornithologist, naturalist, and Director of the San Diego Natural History Museum from 1922 to 1946. Abbott supervised the construction of the museum's current building in Balboa Park, expanded research field trips and expeditions, and participated in important conservation efforts in southern California and the Baja California region. He was instrumental in the preservation of the southern California desert area that became Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.

Goat Canyon Trestle is a wooden trestle in San Diego County, California. At a length of 597–750 feet (182–229 m), it is the world's largest all-wood trestle. Goat Canyon Trestle was built in 1933 as part of the San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway, after one of the many tunnels through the Carrizo Gorge collapsed. The railway had been called the "impossible railroad" upon its 1919 completion. It ran through Baja California and eastern San Diego County before ending in Imperial Valley. The trestle was made of wood, rather than metal, due to temperature fluctuations in the Carrizo Gorge. By 2008, most rail traffic stopped using the trestle.

Canebrake Canyon is a valley at an elevation of 1145 feet in the deserts of Southern California. Canebrake Canyon is found southwest of Mesquite Oasis, northeast of the Tierra Blanca Mountains. An open wilderness of San Diego County, California, it is reached nearby from popular Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and is a remote hiking destination.