Social promotion is an educational practice in which a student is promoted to the next grade at the end of the school year, regardless of whether they have mastered the necessary material or attended school consistently. This practice typically applies to general education students, rather than those in special education. The main objective is to keep students with their peers by age, maintaining their intended social grouping. Social promotion is sometimes referred to as promotion based on seat time—the time the student spends in school. It is based on enrollment criteria for kindergarten, which often requires students to be 4 or 5 years old at the start of the school year, with the goal of allowing them to graduate from high school before turning 19.

English as a second or foreign language refers to the use of English by individuals whose native language is different, commonly among students learning to speak and write English. Variably known as English as a foreign language (EFL), English as a second language (ESL), English for speakers of other languages (ESOL), English as an additional language (EAL), or English as a new language (ENL), these terms denote the study of English in environments where it is not the dominant language. Programs such as ESL are designed as academic courses to instruct non-native speakers in English proficiency, encompassing both learning in English-speaking nations and abroad.

Gifted education is a sort of education used for children who have been identified as gifted or talented.

When children are young, schools begin to analyze the youngsters’ abilities and sort them into clusters based on their predicted success. The system labels the cream of the crop as gifted. Clark (2002) defines giftedness as “only a label that society gives to those who have actualized their ability to an unusually high degree or give evidence that such achievement is imminent”. The American government defines giftedness as “students, children or youth who give evidence of high performance capability in areas such as intellectual, creative, artistic, or leadership capacity, or in specific academic fields, and who require services or activities not ordinarily provided by the school in order to fully develop such capabilities”. Gifted students learn in a different manner and at an accelerated rate compared to their peers in the classroom and therefore require gifted programs to develop and apply their talents.

Ability grouping is the educational practice of grouping students by potential or past achievement for a relevant activity. Ability groups are usually small, informal groups formed within a single classroom. It differs from tracking by being less pervasive, involving much smaller groups, and by being more flexible and informal.

Educational stages are subdivisions of formal learning, typically covering early childhood education, primary education, secondary education and tertiary education. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognizes nine levels of education in its International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) system. UNESCO's International Bureau of Education maintains a database of country-specific education systems and their stages. Some countries divide levels of study into grades or forms for school children in the same year.

Mirman School is an independent, co-educational school for highly gifted children located at 16180 Mulholland Drive in Bel-Air, Los Angeles, California, United States, with 330 pupils aged 5 to 14. Mirman School is accredited by the California Association of Independent Schools (CAIS) and the Western Association of Schools and Colleges WASC for grades K-8. Mirman is one of a handful of schools for the highly gifted in the United States.

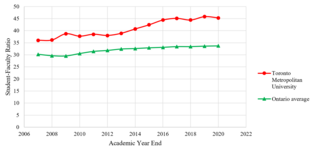

The student–teacher ratio or student–faculty ratio is the number of students who attend a school or university divided by the number of teachers in the institution. For example, a student–teacher ratio of 10:1 indicates that there are 10 students for every one teacher. The term can also be reversed to create a teacher–student ratio.

Tracking is separating students by what is assessed as academic ability into groups for all subjects or certain classes and curriculum within a school. Track assignment is typically based on academic ability, other factors often influence placement. It may be referred to as streaming or phasing in some schools. In a tracking system, the entire school population is assigned to classes according to whether the students' overall achievement is above average, normal, or below average. Students attend academic classes only with students whose overall academic achievement is the same as their own. Tracking generally applies to comprehensive schools, while selective school systems assign the students to different schools.

A Nation Deceived: How Schools Hold Back America's Brightest Students is The Templeton National Report on Acceleration, a report which was published in 2004 and edited by Nicholas Colangelo, Susan G. Assouline, and Miraca Gross. This report argues for the academic acceleration of qualified gifted and talented students, based on the results of studies on outcomes of accelerating and not accelerating high-achieving students. Despite the evidence that acceleration is a beneficial practice when implemented correctly, many teachers and parents are reluctant to accelerate students. The report presents the research on acceleration in an effort to increase the number of students who have access to acceleration.

Academic acceleration is moving students through an educational program at a rate faster or at an age younger than is typical. Students who would benefit from acceleration do not necessarily need to be identified as gifted in a particular subject. Acceleration places them ahead of where they would be in the regular school curriculum. It has been described as a "fundamental need" for gifted students as it provides students with level-appropriate material. The practice occurs worldwide. The bulk of educational research on academic acceleration has been within the United States.

Educational Inequality is the unequal distribution of academic resources, including but not limited to school funding, qualified and experienced teachers, books, physical facilities and technologies, to socially excluded communities. These communities tend to be historically disadvantaged and oppressed. Individuals belonging to these marginalized groups are often denied access to schools with adequate resources and those that can be accessed are so distant from these communities. Inequality leads to major differences in the educational success or efficiency of these individuals and ultimately suppresses social and economic mobility. Inequality in education is broken down into different types: regional inequality, inequality by sex, inequality by social stratification, inequality by parental income, inequality by parent occupation, and many more.

The term twice-exceptional or 2e refers to individuals acknowledged as gifted and neurodivergent. On literal sense, it means a person, is at the same time, very strong or gifted at some task, and very weak or unable in some other task. Due to this duality of their cognitive profile, the strengths as well as weaknesses and struggles may remain unnoticed or unsupported. Also conditions like hyperlexia or precocious development in some aspects, while having difficulties in common or day-to day tasks, these people may frequently face contradictory situations which lead to disbelief, judgements, alienation, and other forms of epistemic injustice. Some related terms are "performace discrepancy", "cognitive discrepancy", "uneven cognitive profile", and "spikey profile". Due to simultaneous combination of abilities and inabilities, these people do not often fit into an age-appropriate or socially-appropriate niche. An extreme form of twice-exceptionalism is Savant syndrome. The individuals often identify with the description of twice-exceptional due to their unique combination of exceptional abilities and neurodivergent traits. The term twice-exceptional first appeared in Dr. James J. Gallagher's 1988 article titled National Agenda for Educating Gifted Students: Statement of Priorities. Twice-exceptional individuals embody two distinct forms of exceptionalism: one being giftedness and the other including at least one aspect of neurodivergence. Giftedness is often defined in various ways and is influenced by entities ranging from local educational boards to national governments; however, one constant among every definition is that a gifted individual has high ability compared to their age-level neurotypical peers. The term neurodivergent describes an individual whose cognitive processes differ from those considered neurotypical and who possesses strengths that exceed beyond the neurotypical population. Therefore, the non-clinical designation of twice-exceptional identifies a gifted person with at least one neurodivergent trait.

The WIDA Consortium is an educational consortium of state departments of education. Currently, 42 U.S. states and the District of Columbia participate in the WIDA Consortium, as well as the Northern Mariana Islands, the United States Virgin Islands, Palau, the Bureau of Indian Education, and the Department of Defense Education Activity. WIDA designs and implements proficiency standards and assessment for grade K-12 students who are English-language learners, as well as a set of proficiency standards and assessments for Spanish language learners. WIDA also provides professional development to educators and conducts research on instructional practices.

Cluster grouping is an educational process in which four to six gifted and talented (GT) or high-achieving students or both are assigned to an otherwise heterogeneous classroom within their grade to be instructed by a teacher who has had specialized training in differentiating for gifted learners. Clustering can be contrasted with other ability-grouping strategies in which high achievers fill their own dedicated class, entirely separate from other students.

Gifted pull-outs are an educational approach in which gifted students are removed from a heterogeneous (mixed-ability) classroom to spend a portion of their time with academic peers. Pull-outs tend to meet one to two hours per week. The students meet with a teacher to engage in enrichment or extension activities that may or may not be related to the curriculum being taught in the regular classroom. Pull-out teachers in some states are not required to have any formal background in gifted education.

The racial achievement gap in the United States refers to disparities in educational achievement between differing ethnic/racial groups. It manifests itself in a variety of ways: African-American and Hispanic students are more likely to earn lower grades, score lower on standardized tests, drop out of high school, and they are less likely to enter and complete college than whites, while whites score lower than Asian Americans.

Multi-age classrooms or composite classes are classrooms with students from more than one grade level. They are created because of the pedagogical choice of a school or school district. They are different from split classes which are formed when there are too many students for one class – but not enough to form two classes of the same grade level. Composite classes are more common in smaller schools; an extreme form is the one-room school.

In the United States, elementary schools are the main point of delivery of primary education, for children between the ages of 4–11 and coming between pre-kindergarten and secondary education.