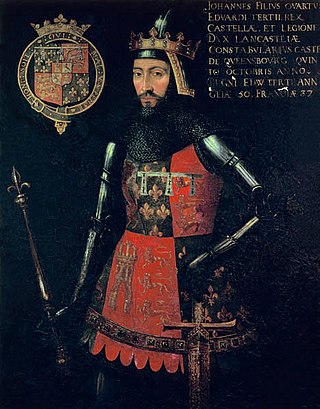

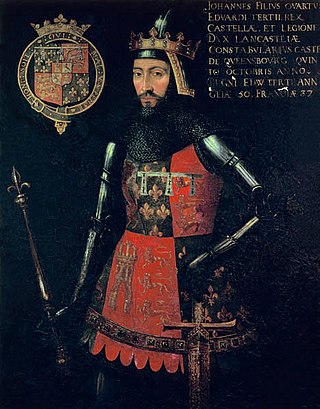

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster was an English-French royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the third surviving son of King Edward III of England, and the father of King Henry IV. Due to Gaunt's royal origin, advantageous marriages, and some generous land grants, he was one of the richest men of his era, and was an influential figure during the reigns of both his father and his nephew, Richard II. As Duke of Lancaster, he is the founder of the royal House of Lancaster, whose members would ascend the throne after his death. His birthplace, Ghent in Flanders, then known in English as Gaunt, was the origin of his name. When he became unpopular later in life, a scurrilous rumour circulated, along with lampoons, claiming that he was actually the son of a Ghent butcher. This rumour, which infuriated him, may have been inspired by the fact that Edward III had not been present at his birth.

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancaster—from which the house was named—for his second son Edmund Crouchback in 1267. Edmund had already been created Earl of Leicester in 1265 and was granted the lands and privileges of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, after de Montfort's death and attainder at the end of the Second Barons' War. When Edmund's son Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, inherited his father-in-law's estates and title of Earl of Lincoln he became at a stroke the most powerful nobleman in England, with lands throughout the kingdom and the ability to raise vast private armies to wield power at national and local levels. This brought him—and Henry, his younger brother—into conflict with their cousin King Edward II, leading to Thomas's execution. Henry inherited Thomas's titles and he and his son, who was also called Henry, gave loyal service to Edward's son King Edward III.

Henry Ward Beecher was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery trial. His rhetorical focus on Christ's love has influenced mainstream Christianity through the 21st century.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1866.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1852.

Charles Reade was a British novelist and dramatist, best known for The Cloister and the Hearth.

Lyman Beecher was a Presbyterian minister, and the father of 13 children, many of whom became noted figures, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Beecher, Edward Beecher, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher, and Thomas K. Beecher.

The title of Earl of Lancaster was created in the Peerage of England in 1267. It was succeeded by the title Duke of Lancaster in 1351, which expired in 1361.

Ellen Price was an English novelist better known as Mrs. Henry Wood. She is best remembered for her 1861 novel East Lynne. Many of her books sold well internationally and were widely read in the United States. In her time, she surpassed Charles Dickens in fame in Australia.

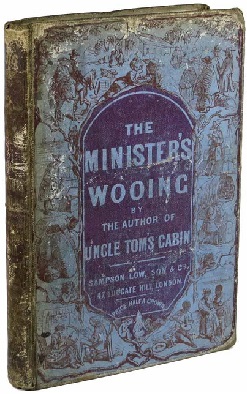

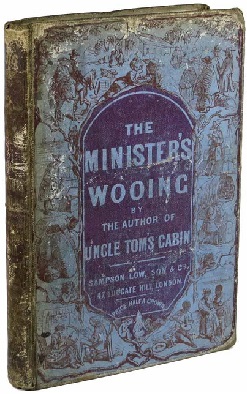

The Minister's Wooing is a historical novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe, first published in 1859. Set in 18th-century New England, the novel explores New England history, highlights the issue of slavery, and critiques the Calvinist theology in which Stowe was raised. Due to similarities in setting, comparisons are often drawn between this work and Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850). However, in contrast to Hawthorne's The Scarlett Letter, The Minister's Wooing is a "sentimental romance"; its central plot revolves around courtship and marriage. Moreover, Stowe's exploration of the regional history of New England deals primarily with the domestic sphere, the New England response to slavery, and the psychological impact of the Calvinist doctrines of predestination and disinterested benevolence.

Victorian literature is English literature during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). The 19th century is considered by some to be the Golden Age of English Literature, especially for British novels. It was in the Victorian era that the novel became the leading literary genre in English. English writing from this era reflects the major transformations in most aspects of English life, from scientific, economic, and technological advances to changes in class structures and the role of religion in society. The number of new novels published each year increased from 100 at the start of the period to 1000 by the end of it. Famous novelists from this period include Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, the three Brontë sisters, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, and Rudyard Kipling.

The sensation novel, also sensation fiction, was a literary genre of fiction that achieved peak popularity in Great Britain in the 1860s and 1870s. Its literary forebears included the melodramatic novels and the Newgate novels, which focused on tales woven around criminal biographies; it also drew on the Gothic, romance, as well as mass market genres. The genre's popularity was conjoined to an expanding book market and growth of a reading public, by-products of the Industrial Revolution. Whereas romance and realism had traditionally been contradictory modes of literature, they were brought together in sensation fiction. The sensation novelists commonly wrote stories that were allegorical and abstract; the abstract nature of the stories gave the authors room to explore scenarios that wrestled with the social anxieties of the Victorian era. The loss of identity is seen in many sensation fiction stories because this was a common social anxiety; in Britain, there was an increased use in record keeping and therefore people questioned the meaning and permanence of identity. The social anxiety regarding identity is reflected in novels such as The Woman in White and Lady Audley's Secret.

Julius John Lankes (1884–1960) was an illustrator, a woodcut print artist, author, and college professor.

Frederick Wadsworth Loring was an American journalist, novelist and poet.

Charles Henry Webb was an American poet, author and journalist. He was particularly known for his parodies and humorous writings.

Avonia Stanhope Jones Brooke was an American actress, best known for tragic roles.

George Vandenhoff was an English actor and elocutionist who performed in Britain and the United States.

Hard Cash, A Matter-of-Fact Romance is an 1863 novel by Charles Reade. The novel is about the poor treatment of patients in private insane asylums, and was part of Reade's drive to reform and improve those institutions.

Elizabeth Monroe Richards Tilton was an American suffragist, a founder of the Brooklyn Woman's Club, and a poetry editor of The Revolution, the newspaper of the National Woman Suffrage Association, founded by woman's rights advocates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Elizabeth Tilton also served on the executive committee of the American Equal Rights Association.

A Terrible Temptation: A Story of the Day is an 1871 sensation novel by Charles Reade. It first appeared serially in Cassell's Magazine in England from March 4 to August 26, 1871.