Related Research Articles

The Milice française, generally called la Milice, was a political paramilitary organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy regime to help fight against the French Resistance during World War II. The Milice's formal head was Prime Minister Pierre Laval, although its chief of operations and de facto leader was Secretary General Joseph Darnand. It participated in summary executions and assassinations, helping to round up Jews and résistants in France for deportation. It was the successor to Darnand's Service d'ordre légionnaire (SOL) militia. The Milice was the Vichy regime's most extreme manifestation of fascism. Ultimately, Darnand envisaged the Milice as a fascist single party political movement for the French state.

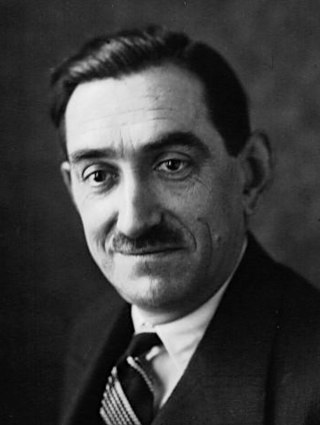

Jacques Doriot was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

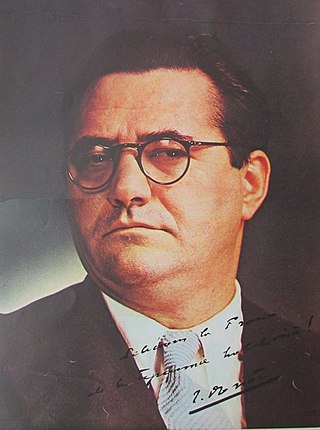

Marcel Déat was a French politician. Initially a socialist and a member of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), he led a breakaway group of right-wing Neosocialists out of the SFIO in 1933. During the occupation of France by Nazi Germany, he founded the collaborationist National Popular Rally (RNP). In 1944, he became Minister of Labour and National Solidarity in Pierre Laval's government in Vichy, before escaping to the Sigmaringen enclave along with Vichy officials after the Allied landings in Normandy. Condemned in absentia for collaborationism, he died while still in hiding in Italy.

Fernand de Brinon, Marquis de Brinon was a French lawyer and journalist who was one of the architects of French collaboration with the Nazis during World War II. He claimed to have had five private talks with Adolf Hitler between 1933 and 1937.

The French Popular Party was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

Philippe Henriot was a French poet, journalist, politician, and Nazi collaborator who served as a minister in the French government at Vichy, where he directed propaganda broadcasts. He was assassinated by the Résistance in 1944.

The Francist Movement was a French fascist and anti-semitic league created by Marcel Bucard in September 1933 that edited the newspaper Le Francisme. Mouvement franciste reached a membership of 10,000 and was financed by the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini. Its members were deemed the francistes or Chemises bleues (Blueshirts) and gave the Roman salute.

The Military Administration in France was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called zone occupée was established in June 1940, and renamed zone nord in November 1942, when the previously unoccupied zone in the south known as zone libre was also occupied and renamed zone sud.

The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism was a unit of the German Army during World War II consisting of collaborationist volunteers from France. Officially designated the 638th Infantry Regiment, it was one of several foreign volunteer units formed in German-occupied Western Europe to participate in the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.

The Révolution nationale was the official ideological program promoted by the Vichy regime which had been established in July 1940 and led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Pétain's regime was characterized by anti-parliamentarism, personality cultism, xenophobia, state-sponsored anti-Semitism, promotion of traditional values, rejection of the constitutional separation of powers, modernity, and corporatism, as well as opposition to the theory of class conflict. Despite its name, the ideological policies were reactionary rather than revolutionary as the program opposed almost every change introduced to French society by the French Revolution.

The National Popular Rally was a French political party and one of the main collaborationist parties under the Vichy regime of World War II.

Paul Jules André Marion was a French Communist and subsequently far right journalist and political activist. He served as the French Minister of Information from 1941 to 1944.

Pierre Firmin Pucheu was a French industrialist, fascist and member of the Vichy government. He became after his marriage the son-in-law of the Belgian architect Paul Saintenoy.

Jacques Chardonne is the pseudonym of French writer Jacques Boutelleau. He was a member of the so-called Groupe de Barbezieux.

Maurice-Ivan Sicard was a French journalist, far right political activist, and Nazi collaborator.

Jean Fontenoy was a French journalist and fascist politician who was a collaborator with Nazi Germany.

La Gerbe was a weekly newspaper of the French collaboration with Nazi Germany during World War II that appeared in Paris from July 1940 till August 1944. Its political-literary line was modeled after Candide and Gringoire, two right-wing newspapers founded in the interwar period.

Jean Bichelonne was a French businessman and member of the Vichy government that governed France during World War II following the occupation of France by Nazi Germany.

The French National-Collectivist Party, originally known as the French National Communist Party, was a minor political group active in the French Third Republic and reestablished in occupied France. Its leader in both incarnations was the sports journalist Pierre Clémenti. It espoused a "national communist" platform noted for its similarities with fascism, and popularized racial antisemitism. The group was also noted for its agitation in support of pan-European nationalism and rattachism, maintaining contacts in both Nazi Germany and Wallonia.

The Sigmaringen enclave was the exiled remnant of France's Nazi-sympathizing Vichy government which fled to Germany during the Liberation of France near the end of World War II in order to avoid capture by the advancing Allied forces. Installed in the requisitioned Sigmaringen Castle as seat of the government-in-exile, Vichy French leader Philippe Pétain and a number of other collaborators awaited the end of the war.

References

Bibliography

- Atkin, Nicholas, The French at War, 1934-1944, Routledge, 2014

- Curtis, Michael, Verdict on Vichy: Power and prejudice in the Vichy France Regime, Phoenix Press, 2004

- Dorléac, Laurence Bertrand , Art of the Defeat: France 1940-1944, Getty Publications, 2008

- Fiss, Karen, Grand Illusion: The Third Reich, the Paris Exposition, and the Cultural Seduction of France, University of Chicago Press, 2009

- Forbes, Robert, For Europe: The French Volunteers of the Waffen-SS, Stackpole Books, 2010

- Littlejohn, David, The Patriotic Traitors , Heinemann, 1972

- Rees, Philip, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right Since 1890 , Simon & Schuster, 1990

- Sprout, Leslie A., The Musical Legacy of Wartime France, University of California Press, 2013

- Sweets, John, Choices in Vichy France: The French Under Nazi Occupation, Oxford University Press, 1986