Related Research Articles

The Meiji era was an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868, to July 30, 1912. The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization by Western powers to the new paradigm of a modern, industrialized nation state and emergent great power, influenced by Western scientific, technological, philosophical, political, legal, and aesthetic ideas. As a result of such wholesale adoption of radically different ideas, the changes to Japan were profound, and affected its social structure, internal politics, economy, military, and foreign relations. The period corresponded to the reign of Emperor Meiji. It was preceded by the Keiō era and was succeeded by the Taishō era, upon the accession of Emperor Taishō.

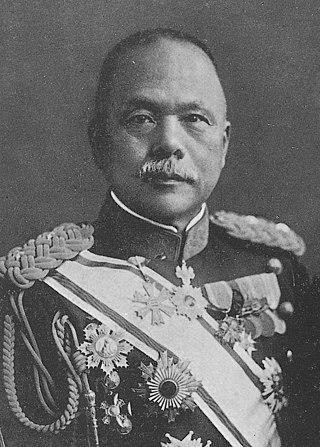

Gensui Prince Yamagata Aritomo was a Japanese statesman and military commander who was twice-elected Prime Minister of Japan, and a leading member of the genrō, an élite group of senior statesmen who dominated Japanese politics after the Meiji Restoration. As the Imperial Japanese Army's inaugural Chief of Staff, he was the chief architect of the Empire of Japan's military and its reactionary ideology. For this reason, some historians consider Yamagata to be the “father” of Japanese militarism. He was also known as Yamagata Kyōsuke.

Zaibatsu is a Japanese term referring to industrial and financial vertically integrated business conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over significant parts of the Japanese economy from the Meiji period to World War II. A zaibatsu's general structure included a family-owned holding company on top, and a bank which financed the other, mostly industrial subsidiaries within them. Although the zaibatsu played an important role in the Japanese economy beginning in 1868, they especially increased in number and importance following the Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and Japan's subsequent attempt to conquer East Asia and the Pacific Rim during the interwar period and World War II. After World War II, they were dissolved by the Allied occupation forces and succeeded by the keiretsu. Equivalents to the zaibatsu can still be found in other countries, such as the chaebol conglomerates of South Korea.

Kazushige Ugaki was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army and cabinet minister before World War II, the 5th principal of Takushoku University, and twice Governor-General of Korea. Nicknamed Ugaki Issei, he served as Foreign Minister of Japan in the Konoe cabinet in 1938.

The Boshin War, sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a coalition seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperial Court.

The Ministry of the Navy was a cabinet-level ministry in the Empire of Japan charged with the administrative affairs of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). It existed from 1872 to 1945.

The Kōdōha or Imperial Way Faction (皇道派) was a political faction in the Imperial Japanese Army active in the 1920s and 1930s. The Kōdōha sought to establish a military government that promoted totalitarian, militaristic and aggressive imperialist ideals, and was largely supported by junior officers. The radical Kōdōha rivaled the moderate Tōseiha for influence in the army until the February 26 Incident in 1936, when it was de facto dissolved and many supporters were disciplined or executed.

Japanese militarism was the ideology in the Empire of Japan which advocated the belief that militarism should dominate the political and social life of the nation, and the belief that the strength of the military is equal to the strength of a nation. It was most prominent from the start of conscription after the Meiji Restoration until the Japanese defeat in World War II, roughly 1873 to 1945. Since then, pacifism has been enshrined in the postwar Constitution of Japan as one of its key tenets.

The political situation in Japan (1914–44) dealt with the realities of the two World Wars and their effect on Japanese national policy.

Political parties appeared in Japan after the Meiji Restoration, and gradually increased in importance after the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution and the creation of the Diet of Japan. During the Taishō period, parliamentary democracy based on party politics temporarily succeeded in Japan, but in the 1930s the political parties were eclipsed by the military, and were dissolved in the 1940s during World War II.

The Satsuma Domain, briefly known as the Kagoshima Domain, was a domain (han) of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan during the Edo period from 1602 to 1871.

Tetsuzan Nagata was a Japanese military officer and general of the Imperial Japanese Army best known as the victim of the Aizawa Incident in August 1935.

The Government of Meiji Japan was the government that was formed by politicians of the Satsuma Domain and Chōshū Domain in the 1860s. The Meiji government was the early government of the Empire of Japan.

CountHasegawa Yoshimichi was a field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army and Japanese Governor General of Korea from 1916 to 1919. His Japanese decorations included Order of the Golden Kite and Order of the Chrysanthemum.

The Chōshū Domain, also known as the Hagi Domain, was a domain (han) of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan during the Edo period from 1600 to 1871.

CountKabayama Sukenori was a Japanese samurai military leader and statesman. He was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy. He later became the first Japanese Governor-General of Taiwan during the island's period as a Japanese colony. He is also sometimes referred to as Kabayama Motonori.

The Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office, also called the Army General Staff, was one of the two principal agencies charged with overseeing the Imperial Japanese Army.

The Seikanron was a major political debate in Japan during 1873 regarding a punitive expedition against Korea. The Seikanron split the Meiji government and the restoration coalition that had been established against the bakufu, but resulted in a decision not to send a military expedition to Korea.

The Imperial Japanese Armed Forces were the unified forces of the Empire of Japan. Formed during the Meiji Restoration in 1868, they were disbanded in 1945, shortly after Japan's defeat to the Allies of World War II; the revised Constitution of Japan, drafted during the Allied occupation of Japan, replaced the IJAF with the present-day Japan Self-Defense Forces.

Hokushin-ron was a political doctrine of the Empire of Japan before World War II that stated that Manchuria and Siberia were Japan's sphere of interest and that the potential value to Japan for economic and territorial expansion in those areas was greater than elsewhere. Its supporters were sometimes called the Strike North Group.

References

- Beasley, W.G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822168-1.

- Buruma, Ian (2004). Inventing Japan, 1854-1964 . Modern Library. ISBN 0-8129-7286-4.

- Gow, Ian (2004). Military Intervention in Pre-War Japanese Politics: Admiral Kato Kanji and the Washington System'. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1315-8.

- Harries, Meirion (1994). Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army. Random House; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-679-75303-6.

- Samuels, Richard J (2007). Securing Japan: Tokyo's Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4612-2.

- Spector, Ronald (1985). Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan . Vintage. ISBN 0-394-74101-3.

- Zhukov, Y.M., ed. (1975). The Rise and Fall of the Gunbatsu: A Study in Military History. Moscow: Progress Publishers.