H. C. Erik Midelfort | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hans Christian Erik Midelfort April 17, 1942 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Occupation(s) | Scholar, Author, Professor Emeritus of History and Religious Studies at University of Virginia |

| Known for | German Reformation and the history of Christianity in Early Modern Europe |

| Notable work | Mad Princes of Renaissance Germany A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany Exorcism and Enlightenment: Johann Joseph Gassner and the Demons of 18th-Century Germany |

Hans Christian Erik Midelfort (born April 17, 1942), is C. Julian Bishko Professor Emeritus of History and Religious Studies at the University of Virginia. He is a specialist of the German Reformation and the history of Christianity in Early Modern Europe. [1]

Midelfort was born in Eau Claire, Wisconsin and attended Yale University, where he obtained a Bachelor of Arts in history in 1964. He remained at Yale for graduate studies in history under the supervision of Jaroslav Pelikan and other noted scholars such as Hajo Holborn, J. H. Hexter, and Edmund S. Morgan. Midelfort graduated from Yale University in 1970. His first published work Witch Hunting in Southwestern Germany, 1562–1684: The Social and Intellectual Foundations [2] was published by Stanford University Press, and was awarded the 1973 Gustav O. Arlt Award in the Humanities by the Council of Graduate Schools.

Midelfort was a professor at Stanford University between 1968 and 1970, and he has also been a visiting scholar at University of Bern, Universität Stuttgart, Harvard University, and at Oxford University, where he was a visiting scholar at Wolfson College and visiting fellow at All Souls College. Midelfort was member of the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia from 1970 until his retirement in May 2008 when he delivered his final undergraduate lecture on the topic of "Magic and Modernity." From 1996 until 2001 Midelfort served as principal of Brown College, an undergraduate residential college at the University of Virginia. He appeared in Eduardo Montes-Bradley's film Monroe Hill. [3]

In addition to his early work on witchcraft, Midelfort is best known for "Mad Princes of Renaissance Germany" [4] and A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany. [5] Both studies on madness were awarded the Roland Bainton Prize for the best book of the year in History and Theology by the Sixteenth Century Society and Conference. Midelfort is one of only two scholars to win the award twice. Phi Beta Kappa gave its Ralph Waldo Emerson Award to A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany. More recently, Midelfort published Exorcism and Enlightenment: Johann Joseph Gassner and the Demons of 18th-Century Germany [6] which emerged from his time as lecturer-in-residence as the Terry Lecturer in Yale University.

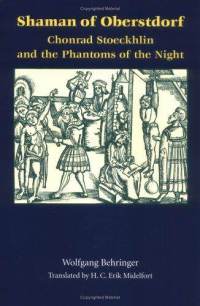

Because of his extensive work in translations from German, Midelfort is well known for strengthening connections between his German and American colleagues. Among the seminal works Midelfort translated from German on the Reformation are Peter Blickle's The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War from a New Perspective, [7] and Bernd Moeller's Imperial Cities and the Reformation, Three Essays. [8] He has also translated Wolfgang Behringer's Shaman of Oberstdorf, Rainer Decker's Witchcraft and the Papacy, and Martin Mulsow's Enlightenment Underground.Midelfort also edits a series of original books and translations on early modern German history published by the University of Virginia Press.

Midelfort has been awarded grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. In 2004 Midelfort was the recipient of a festschrift, or commemorative volume, presented by German colleagues: Wider alle Hexerei und Teufelswerk: Die europäische Hexenverfolgung und ihre Auswirkungen auf Südwestdeutschland, Midelfort received a second festschrift, Ideas and Cultural Margins in Early Modern Germany (edited by Marjorie Elizabeth Plummer and Robin Barnes). Midelfort spent the spring of 2011 as a fellow of the American Academy in Berlin and the recipient of the Ellen Maria Gorrissen Prize.

Most recently, a collection of Midelfort articles and other writings has been published as Witchcraft, Madness, Society, and Religion in Early Modern Germany: A Ship of Fools. [9]

H. C. Erik Midelfort is married to Anne McKeithen. They live in Charlottesville, Virginia.