Habitat conservation is a management practice that seeks to conserve, protect and restore habitats and prevent species extinction, fragmentation or reduction in range. It is a priority of many groups that cannot be easily characterized in terms of any one ideology.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is the primary law in the United States for protecting and conserving imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation", the ESA was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. The Supreme Court of the United States described it as "the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species enacted by any nation". The purposes of the ESA are two-fold: to prevent extinction and to recover species to the point where the law's protections are not needed. It therefore "protect[s] species and the ecosystems upon which they depend" through different mechanisms. For example, section 4 requires the agencies overseeing the Act to designate imperiled species as threatened or endangered. Section 9 prohibits unlawful 'take,' of such species, which means to "harass, harm, hunt..." Section 7 directs federal agencies to use their authorities to help conserve listed species. The Act also serves as the enacting legislation to carry out the provisions outlined in The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) was the first act of the United States Congress to call specifically for an ecosystem approach to wildlife management.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has a number of programs aimed at Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation, which include lands traditionally inhabited by the Mission blue butterfly, an endangered species. A recovery plan, drawn up by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1984, outlined the need to protect Mission blue habitat and to repair habitat damaged by urbanization, off highway vehicle traffic, and invasion by exotic, non-native plants. An example of the type of work being done by governmental and citizen agencies can be found at the Marin Headlands in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. In addition, regular wildfires have opened new habitat conservation opportunities as well as damaging existing ones.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was first passed in 1973 and forms the basis of biodiversity and endangered species protection in the United States. The original purpose of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 was to prevent species endangerment and extinction due to the human impact on natural ecosystems. The three most powerful sections of the ESA are Sections 4, 7 and 9. Section 4 allows the Secretaries of Interior and Commerce to list species as threatened or endangered based on best available data. Section 7 requires federal agencies to consult with Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) or National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) before taking any action that may threaten a listed species. Section 9 forbids the taking of an endangered species. The first amendment to the ESA was passed by the 95th United States Congress in 1978 to "introduce some flexibility into the Endangered Species Act".

Mitigation banking is a market-based system of debits and credits that involves restoration, creation, or enhancement of wetlands to compensate for unavoidable impacts to a wetland in another location. It involves a system of mitigation banks, sites where projects to restore, create, or enhance wetlands can be carried out in advance of impacts. The outcomes of these projects are valued through the creation of compensatory mitigation credits that can be purchased from mitigation banks to offset the negative impacts of developments or agriculture expansion on wetlands and aquatic habitats. This process is generally conducted with the aim of achieving no net loss of function and value for specific aquatic habitats, such as in terms of the biodiversity or ecosystem services provided by a wetland.

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act is a United States federal statute that protects two species of eagle. The bald eagle was chosen as a national emblem of the United States by the Continental Congress of 1782 and was given legal protection by the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940. This act was expanded to include the golden eagle in 1962. Since the original Act, the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act has been amended several times. It currently prohibits anyone, without a permit issued by the Secretary of the Interior, from "taking" bald eagles. Taking is described to include their parts, nests, or eggs, molesting or disturbing the birds. The Act provides criminal penalties for persons who "take, possess, sell, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase or barter, transport, export or import, at any time or any manner, any bald eagle ... [or any golden eagle], alive or dead, or any part, nest, or egg thereof."

A distinct population segment (DPS) is the smallest division of a taxonomic species permitted to be protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Species, as defined in the Act for listing purposes, is a taxonomic species or subspecies of plant or animal, or in the case of vertebrate species, a distinct population segment.

Biodiversity banking, also known as biodiversity trading, conservation banking, mitigation banking, habitat banking, compensatory habitat, or set-asides, describes a market-based framework for biodiversity offsetting where offsets can be traded in the form of credits to offset negative environmental impacts of development projects or activities. This involves biodiversity banks, areas with biodiversity value. On the site of a biodiversity bank, conservation activities may be carried out to preserve, restore, enhance, or conserve biodiversity. The outcomes of projects carried out at biodiversity banks are valued in the form of credits, which can be purchased as a way to offset unavoidable adverse environmental impacts, often with the aim of achieving no net loss of biodiversity.

Conservation-reliant species are animal or plant species that require continuing species-specific wildlife management intervention such as predator control, habitat management and parasite control to survive, even when a self-sustainable recovery in population is achieved.

Critical habitat refers to specific geographic areas essential to the conservation of a listed endangered species, though the area need not actually be occupied by the species at the time it is designated. Critical habitat is a legal designation of land use defined within the U.S. Endangered Species Act-ESA. Contrary to common belief, designating an area as critical habitat does not preclude that area from development. A critical habitat designation only affects federal agency actions. Such actions include federally funded activities or activities requiring a federal permit that may negatively affect the quality of habitat for a listed species. This law also defines that there may be no "take" of a listed species from the designated area. This land designation aims to protect vital habitat for endangered species by preserving areas that are able to meet the identified needs for the target species. This is a key feature of conservation as outlined in the ESA.

An incidental take permit is a permit issued under Section 10 of the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA) to private, non-federal entities undertaking otherwise lawful projects that might result in the take of an endangered or threatened species. Application for an incidental take permit is subject to certain requirements, including preparation by the permit applicant of a conservation plan.

The LIFE programme is the European Union's funding instrument for the environment and climate action. The general objective of LIFE is to contribute to the implementation, updating and development of EU environmental and climate policy and legislation by co-financing projects with European added value. LIFE began in 1992 and to date there have been five phases of the programme. During this period, LIFE has co-financed some 4600 projects across the EU, with a total contribution of approximately 6.5 billion Euros to the protection of the environment and of climate. For the next phase of the programme (2021–2027) the European Commission proposed to raise the budget to 5.45 billion Euro.

Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) was defined by the U.S. Congress in the 1996 amendments to the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, or Magnuson-Stevens Act, as "those waters and substrate necessary to fish for spawning, breeding, feeding or growth to maturity." Implementing regulations clarified that waters include all aquatic areas and their physical, chemical, and biological properties; substrate includes the associated biological communities that make these areas suitable for fish habitats, and the description and identification of EFH should include habitats used at any time during the species' life cycle. EFH includes all types of aquatic habitat, such as wetlands, coral reefs, sand, seagrasses, and rivers.

The Bay checkerspot is a butterfly endemic to the San Francisco Bay region of the U.S. state of California. It is a federally threatened species, as a subspecies of Euphydryas editha.

Sierra Club v. Babbitt, 15 F. Supp. 2d 1274, is a United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama case in which the Sierra Club and several other environmental organizations and private citizens challenged the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Plaintiffs filed action seeking declaratory injunctive relief regarding two incidental take permits (ITPs) issued by the FWS for the construction of two isolated high-density housing complexes in habitat of the endangered Alabama beach mouse. The District Court ruled that the FWS must reconsider its decision to allow high-density development on the Alabama coastline that might harm the endangered Alabama beach mouse. The District Court found that the FWS violated both the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) by permitting construction on the dwindling beach mouse habitat.

The Hawaii longline fishery is managed under Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council’s (WPRFMC's) Pelagics Fisheries Ecosystem Plan. Through this plan, the WPRFMC has introduced logbooks, observers, vessel monitoring systems, fishing gear modifications and spatial management for the Hawaii longline fishery. Until relatively recently, the main driver for management of the Hawaii longline fishery has been bycatch and not fishery resources.

Conservation banking is an environmental market-based method designed to offset adverse effects, generally, to species of concern, are threatened, or endangered and protected under the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA) through the creation of conservation banks. Conservation banking can be viewed as a method of mitigation that allows permitting agencies to target various natural resources typically of value or concern, and it is generally contemplated as a protection technique to be implemented before the valued resource or species will need to be mitigated. The ESA prohibits the "taking" of fish and wildlife species which are officially listed as endangered or threatened in their populations. However, under section 7(a)(2) for Federal Agencies, and under section 10(a) for private parties, a take may be permissible for unavoidable impacts if there are conservation mitigation measures for the affected species or habitat. Purchasing “credits” through a conservation bank is one such mitigation measure to remedy the loss.

Kawailoa Wind Farm is a wind farm near the Waimea Valley, on the North Shore of Oahu. Commissioned in 2011, it comprises 28 wind turbines. At maximum capacity the farm is able to produce 69 MW. Kawailoa Wind Farm has been operational since 2012 and is a part of Hawaii's renewable energy efforts. Despite its clean energy, there are unintended ecosystem impacts on some native species of birds and bats, and efforts to mitigate these threats are ongoing.

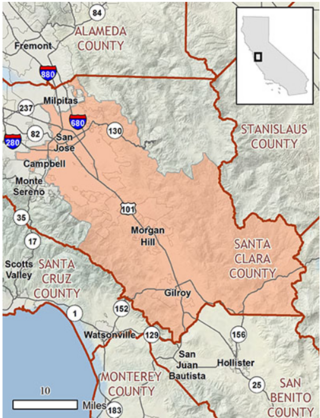

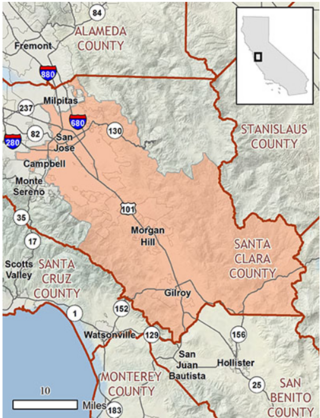

The Santa Clara Valley Habitat Conservation Plan (SCVHCP), also known as the Santa Clara Valley Habitat Plan, is an initiative issued in 2012 by the County of Santa Clara, the City of San José, the City of Morgan Hill, the City of Gilroy, the Santa Clara Valley Water District (SCVWD), and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). These governmental agencies are collectively called the "Local Partners" in regards to the Santa Clara Valley Habitat Conservation Plan. The plan's goal is to protect and encourage the growth of endangered species in Santa Clara County. It is a 50-year plan, costing an estimated $660 million as of 2012.