Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between them and their in-laws. It is considered a cultural universal, but the definition of marriage varies between cultures and religions, and over time. Typically, it is an institution in which interpersonal relationships, usually sexual, are acknowledged or sanctioned. In some cultures, marriage is recommended or considered to be compulsory before pursuing any sexual activity. A marriage ceremony is called a wedding.

This article is about the demographic history of the United States.

A wife is a female in a marital relationship. A woman who has separated from her partner continues to be a wife until the marriage is legally dissolved with a divorce judgement. On the death of her partner, a wife is referred to as a widow. The rights and obligations of a wife in relation to her partner and her status in the community and in law vary between cultures and have varied over time.

A mail-order bride is a woman who lists herself in catalogs and is selected by a man for marriage. In the twentieth century, the trend was primarily towards women living in developing countries seeking men in more developed nations. The majority of the women making use of these services in the twentieth-century and twenty-first-century are from Southeast Asia, countries of the former Eastern Bloc and from Latin America. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, large numbers of eastern European women have advertised themselves in such a way, primarily from Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia and Moldova. Men who list themselves in such publications are referred to as "mail-order husbands", although this is much less common.

In demography, demographic transition is a phenomenon and theory which refers to the historical shift from high birth rates and high death rates in societies with minimal technology, education and economic development, to low birth rates and low death rates in societies with advanced technology, education and economic development, as well as the stages between these two scenarios. Although this shift has occurred in many industrialized countries, the theory and model are frequently imprecise when applied to individual countries due to specific social, political and economic factors affecting particular populations.

Marriageable age is the general age, as a legal age or as the minimum age subject to parental, religious or other forms of social approval, at which a person is legitimately allowed for marriage. Age and other prerequisites to marriage vary between jurisdictions, but in the vast majority of jurisdictions, the marriage age as a right is set at the age of majority. Nevertheless, most jurisdictions allow marriage at a younger age with parental or judicial approval, and some also allow adolescents to marry if the female is pregnant. The age of marriage is most commonly 18 years old, but there are variations, some higher and some lower. The marriageable age should not be confused with the age of majority or the age of consent, though they may be the same in many places.

Child marriage is a marriage or similar union, formal or informal, between a child under a certain age – typically age 18 – and an adult or another child. The vast majority of child marriages are between a girl and a man, and are rooted in gender inequality.

A shotgun wedding is a wedding which is arranged in order to avoid embarrassment due to premarital sex which can possibly lead to an unintended pregnancy. The phrase is a primarily American colloquialism, termed as such based on a stereotypical scenario in which the father of the pregnant bride-to-be threatens the reluctant groom with a shotgun in order to ensure that he follows through with the wedding.

Forced marriage is a marriage in which one or more of the parties is married without their consent or against their will. A marriage can also become a forced marriage even if both parties enter with full consent if one or both are later forced to stay in the marriage against their will.

A cousin marriage is a marriage where the spouses are cousins. The practice was common in earlier times, and continues to be common in some societies today, though in some jurisdictions such marriages are prohibited. Worldwide, more than 10% of marriages are between first or second cousins. Cousin marriage is an important topic in anthropology and alliance theory.

The middle of the 20th century was marked by a significant and persistent increase in fertility rates in many countries of the world, especially in the Western world. The term baby boom is often used to refer to this particular boom, generally considered to have started immediately after World War II, although some demographers place it earlier or during the war. This terminology led to those born during this baby boom being nicknamed the baby boomer generation.

The history of the family is a branch of social history that concerns the sociocultural evolution of kinship groups from prehistoric to modern times. The family has a universal and basic role in all societies. Research on the history of the family crosses disciplines and cultures, aiming to understand the structure and function of the family from many viewpoints. For example, sociological, ecological or economical perspectives are used to view the interrelationships between the individual, their relatives, and the historical time. The study of family history has shown that family systems are flexible, culturally diverse and adaptive to ecological and economical conditions.

Marriage in China has undergone change during the country's reform and opening period, especially as a result of new legal policies such as the New Marriage Law of 1950 and the Family planning policy in place from 1979 to 2015. The major transformation in the twentieth century is characterized by the change from traditional structures for Chinese marriage, such as arranged marriage, to one where the freedom to choose one’s partner is generally respected. However, both parental and cultural pressures are still placed on many individuals, especially women, to choose socially and economically advantageous marriage partners. While divorce remains rare in China, the 1.96 million couples applying for divorce in 2010 represented a rate 14% higher than the year before and doubled from ten years ago. Despite this rising divorce rate, marriage is still thought of as a natural part of the life course and as a responsibility of good citizenship in China.

Women in the Middle Ages in Europe occupied a number of different social roles. Women held the positions of wife, mother, peasant, artisan, and nun, as well as some important leadership roles, such as abbess or queen regnant. The very concept of woman changed in a number of ways during the Middle Ages, and several forces influenced women's roles during their period.

Marriage in Japan is a legal and social institution at the center of the household. Couples are legally married once they have made the change in status on their family registration sheets, without the need for a ceremony. Most weddings are held either according to Shinto traditions or in chapels according to Christian marriage traditions.

Arranged marriage is a type of marital union where the bride and groom are primarily selected by individuals other than the couple themselves, particularly by family members such as the parents. In some cultures a professional matchmaker may be used to find a spouse for a young person.

Demographically, as in other more recent and thus better documented pre-modern societies, papyrus evidence from Roman Egypt suggests the demographic profile of the Roman Empire had high infant mortality, a low marriage age, and high fertility within marriage. Perhaps half of the Roman subjects died by the age of 5. Of those still alive at age 10, half would die by the age of 50.

The Western European marriage pattern is a family and demographic pattern that is marked by comparatively late marriage, especially for women, with a generally small age difference between the spouses, a significant proportion of women who remain unmarried, and the establishment of a neolocal household after the couple has married. In 1965, John Hajnal posited that Europe could be divided into two areas characterized by a different patterns of nuptiality. To the west of the line, marriage rates and thus fertility were comparatively low and a significant minority of women married late or remained single and most families were nuclear; to the east of the line and in the Mediterranean and particular regions of Northwestern Europe, early marriage and extended family homes were the norm and high fertility was countered by high mortality.

A single woman in the Middle Ages was a woman born between the 5th and 15th century who did not marry. This category of single women does not include widows or divorcees, which are terms used to describe women who were married at one point in their lives. During the Middle Ages in Europe, lifelong spinsters came from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds, though elite women were less likely to be single than peasants or townswomen.

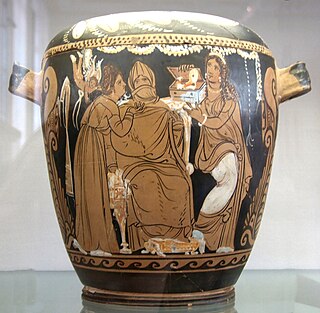

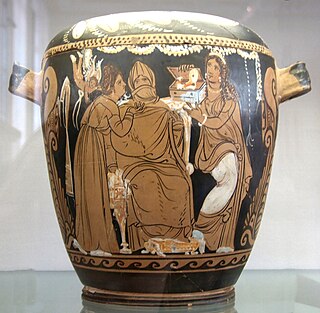

Marriage in ancient Greece had less of a basis in personal relationships and more in social responsibility. The goal and focus of all marriages was intended to be reproduction, making marriage an issue of public interest. Marriages were usually arranged by the parents; on occasion professional matchmakers were used. Each city was politically independent and each had its own laws concerning marriage. For the marriage to be legal, the woman's father or guardian gave permission to a suitable man who could afford to marry. Orphaned daughters were usually married to uncles or cousins. Wintertime marriages were popular due to the significance of that time to Hera, the goddess of marriage. The couple participated in a ceremony which included rituals such as veil removal, but it was the couple living together that made the marriage legal. Marriage was understood to be the official transition from childhood into adulthood for women.