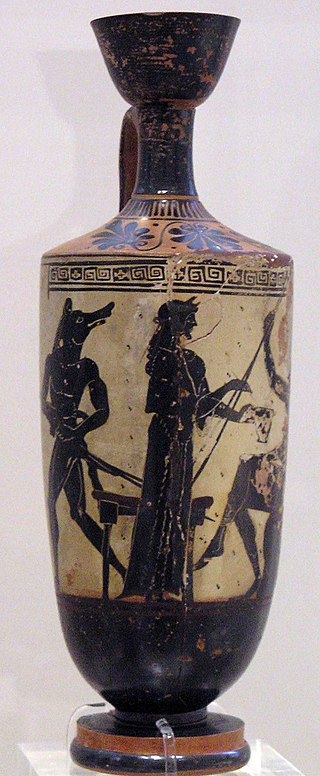

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Demeter is the Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over crops, grains, food, and the fertility of the earth. Although she is mostly known as a grain goddess, she also appeared as a goddess of health, birth, and marriage, and had connections to the Underworld. She is also called Deo. In Greek tradition, Demeter is the second child of the Titans Rhea and Cronus, and sister to Hestia, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus. Like her other siblings but Zeus, she was swallowed by her father as an infant and rescued by Zeus.

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone, also called Kore or Cora, is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld after her abduction by and marriage to her uncle Hades, the king of the underworld.

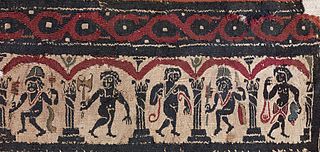

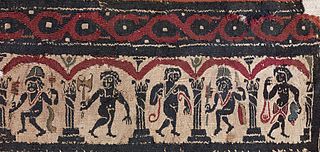

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates (mystai). The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy associated with the particulars of the initiation and the ritual practice, which may not be revealed to outsiders. The most famous mysteries of Greco-Roman antiquity were the Eleusinian Mysteries, which predated the Greek Dark Ages. The mystery schools flourished in Late Antiquity; Emperor Julian, of the mid 4th century, is believed by some scholars to have been associated with various mystery cults—most notably the mithraists. Due to the secret nature of the school, and because the mystery religions of Late Antiquity were persecuted by the Christian Roman Empire from the 4th century, the details of these religious practices are derived from descriptions, imagery and cross-cultural studies. Much information on the Mysteries comes from Marcus Terentius Varro.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Eleusis in ancient Greece. They are considered the "most famous of the secret religious rites of ancient Greece". Their basis was an old agrarian cult, and there is some evidence that they were derived from the religious practices of the Mycenean period. The Mysteries represented the myth of the abduction of Persephone from her mother Demeter by the king of the underworld Hades, in a cycle with three phases: the descent (loss), the search, and the ascent, with the main theme being the ascent of Persephone and the reunion with her mother. It was a major festival during the Hellenic era, and later spread to Rome. Similar religious rites appear in the agricultural societies of the Near East and in Minoan Crete.

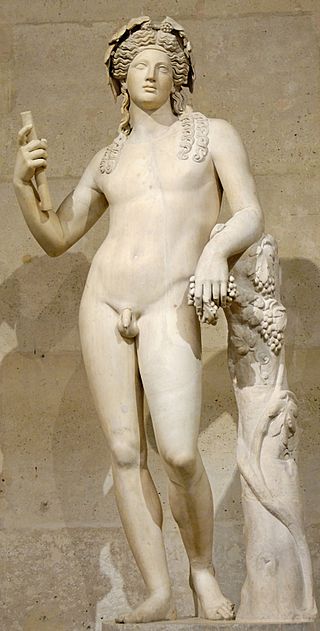

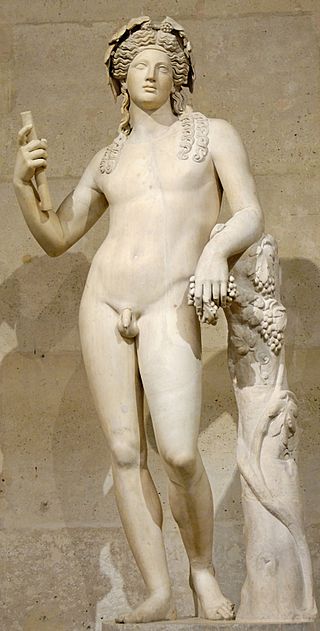

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus by the Greeks for a frenzy he is said to induce called baccheia. As Dionysus Eleutherius, his wine, music, and ecstatic dance free his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subvert the oppressive restraints of the powerful. His thyrsus, a fennel-stem sceptre, sometimes wound with ivy and dripping with honey, is both a beneficent wand and a weapon used to destroy those who oppose his cult and the freedoms he represents. Those who partake of his mysteries are believed to become possessed and empowered by the god himself.

The Thesmophoria was an ancient Greek religious festival, held in honor of the goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone. It was held annually, mostly around the time that seeds were sown in late autumn – though in some places it was associated with the harvest instead – and celebrated human and agricultural fertility. The festival was one of the most widely celebrated in the Greek world. It was restricted to adult women, and the rites practised during the festival were kept secret. The most extensive sources on the festival are a comment in a scholion on Lucian, explaining the festival, and Aristophanes' play Thesmophoriazusae, which parodies the festival.

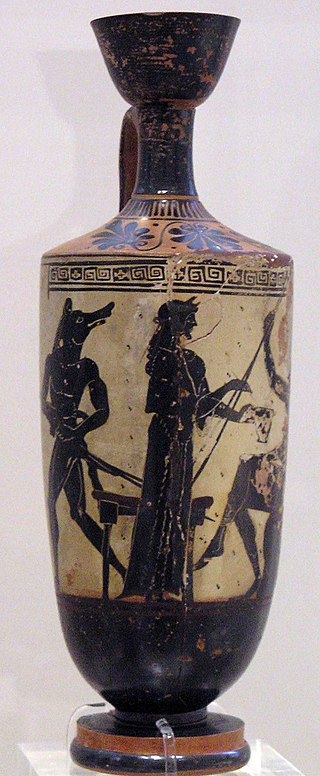

Triptolemus also known as Buzyges, was a hero in Greek mythology, central to the Eleusinian Mysteries. He was either a mortal prince and the eldest son of King Celeus of Eleusis, or according to Pseudo-Apollodorus' Bibliotheca (I.V.2), either the divine son of Gaia and Oceanus, or the grandson of Hermes through Eleusis. He was the ancestor to a royal priestly caste of the Eleusinian Mysteries, who claimed to be Buzygae (Βουζύγαι), that taught agriculture and performed secret rites and rituals, of which Pericles was its most famous descendant.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Iacchus was a minor deity, of some cultic importance, particularly at Athens and Eleusis in connection with the Eleusinian mysteries, but without any significant mythology. He perhaps originated as the personification of the ritual exclamation Iacche! cried out during the Eleusinian procession from Athens to Eleusis. He was often identified with Dionysus, perhaps because of the resemblance of the names Iacchus and Bacchus, another name for Dionysus. By various accounts he was a son of Demeter, or a son of Persephone, identical with Dionysus Zagreus, or a son of Dionysus.

Kykeon was an Ancient Greek drink of various descriptions. Some were made mainly of water, barley and naturally occurring substances. Others were made with wine and grated cheese. It is widely believed that kykeon usually refers to a psychoactive compounded brew, as in the case of the Eleusinian Mysteries. A kykeon was used at the climax of the Eleusinian Mysteries to break a sacred fast, but it is also mentioned as a favourite drink of Greek peasants.

Elefsina or Eleusis is a suburban city and municipality in Athens metropolitan area. It belongs to West Attica regional unit of Greece. It is located in the Thriasio Plain, at the northernmost end of the Saronic Gulf. North of Elefsina are Mandra and Magoula, while Aspropyrgos is to the northeast.

The Anthesteria was one of the four Athenian festivals in honor of Dionysus. It was held each year from the 11th to the 13th of the month of Anthesterion, around the time of the January or February full moon. The three days of the feast were called Pithoigia, Choës, and Chytroi.

Winnowing is a process by which chaff is separated from grain. It can also be used to remove pests from stored grain. Winnowing usually follows threshing in grain preparation. In its simplest form, it involves throwing the mixture into the air so that the wind blows away the lighter chaff, while the heavier grains fall back down for recovery. Techniques included using a winnowing fan or using a tool on a pile of harvested grain.

The festival of the Skira or Skirophoria in the calendar of ancient Athens, closely associated with the Thesmophoria, marked the dissolution of the old year in May/June.

In ancient Greek religion and myth, the epithet Brimo may be applied to any of several goddesses with an inexorable, dreaded and vengeful aspect that is linked to the land of the Dead: Hecate, Persephone, Demeter Erinyes—the angry, bereft Demeter—or Cybele. Brimo is the "furious" aspect of the Furies. In the solemn moment when Medea picks the dire underworld root for Jason, she calls seven times upon Brimo, "she who haunts the night, the Nursing Mother [Kourotrophos]. In black weed and murky gloom she dwells, Queen of the Dead".

The cult of Dionysus was strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni, and its characteristic symbols were the bull, the serpent, tigers/leopards, ivy, and wine. The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus, as well as the phallic processions. Initiates worshipped him in the Dionysian Mysteries, which were comparable to and linked with the Orphic Mysteries, and may have influenced Gnosticism. Orpheus was said to have invented the Mysteries of Dionysus.

The Archeological Museum of Eleusis is a museum in Eleusis, Attica, Greece. The museum is located inside the archaeological site of Eleusis. Built in 1890, by the plans of the German architect Kaverau, to keep the findings of the excavations, and after two years (1892) was extended under the plans of the Greek architect J. Mousis.

The Sacred Way, in ancient Greece, was the road from Athens to Eleusis. It was so called because it was the route taken by a procession celebrating the Eleusinian Mysteries. The procession to Eleusis began at the Sacred Gate in the Kerameikos on the 19th Boedromion.

The festival calendar of Classical Athens involved the staging of many festivals each year. This includes festivals held in honor of Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hermes, and Herakles. Other Athenian festivals were based around family, citizenship, sacrifice, and women. There were at least 120 festival days each year.

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Eubuleus is a god known primarily from devotional inscriptions for mystery religions. The name appears several times in the corpus of the so-called Orphic gold tablets spelled variously, with forms including Euboulos, Eubouleos and Eubolos. It may be an epithet of the central Orphic god, Dionysus or Zagreus, or of Zeus in an unusual association with the Eleusinian Mysteries. Scholars of the late 20th and early 21st centuries have begun to consider Eubuleus independently as "a major god" of the mysteries, based on his prominence in the inscriptional evidence. His depiction in art as a torchbearer suggests that his role was to lead the way back from the Underworld.

The Priestess of Demeter and Kore, sometimes referred to as the High Priestess of Demeter, was the High Priestess of the Goddesses Demeter and Persephone (Kore) in the Telesterion in Eleusis in Ancient Athens. It was one of the highest religious offices in Ancient Athens, and its holder enjoyed great prestige. It was likely the oldest priesthood in Athens, and also the most lucrative priesthood in all of Attica.