The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It orbits at an average distance of 384400 km, about 30 times the planet's diameter. The Moon always presents the same side to Earth, because gravitational pull has locked its rotation to the planet. This results in the lunar day of 29.5 days matching the lunar month. The Moon's gravitational pull – and to a lesser extent the Sun's – are the main drivers of the tides.

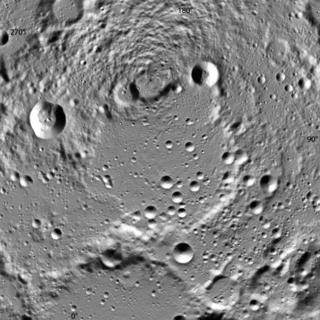

The South Pole–Aitken basin is an immense impact crater on the far side of the Moon. At roughly 2,500 km (1,600 mi) in diameter and between 6.2 and 8.2 km (3.9–5.1 mi) deep, it is one of the largest known impact craters in the Solar System. It is the largest, oldest, and deepest basin recognized on the Moon. It is estimated that it was formed 4.2 to 4.3 billion years ago, during the Pre-Nectarian epoch. It was named for two features on opposite sides of the basin: the lunar South Pole at one end and the crater Aitken on the northern end. The outer rim of this basin can be seen from Earth as a huge mountain chain located on the Moon's southern limb, sometimes informally called "Leibnitz mountains".

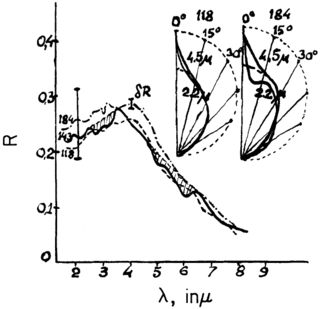

Enceladus is the sixth-largest moon of Saturn. It is about 500 kilometers in diameter, about a tenth of that of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. It is mostly covered by fresh, clean ice, making it one of the most reflective bodies of the Solar System. Consequently, its surface temperature at noon reaches only −198 °C, far colder than a light-absorbing body would be. Despite its small size, Enceladus has a wide range of surface features, ranging from old, heavily cratered regions to young, tectonically deformed terrain.

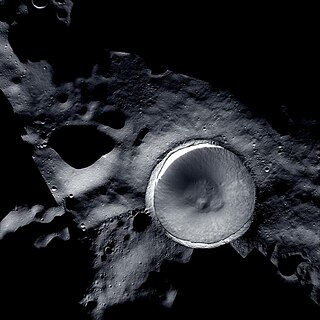

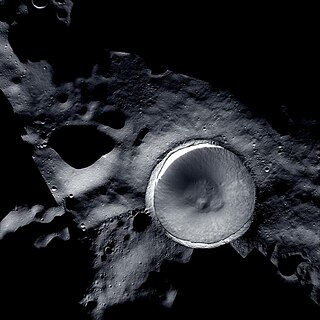

Amundsen is a large lunar impact crater located near the south pole of the Moon, named after the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. It lies along the southern lunar limb, and so is viewed from the side by an observer on the Earth. To the northwest is the crater Scott, a formation of similar dimensions that is named for another Antarctic explorer. Nobile is attached to the western rim.

Hermite is a lunar impact crater located along the northern lunar limb, close to the north pole of the Moon. Named for Charles Hermite, the crater was formed roughly 3.91 billion years ago.

Shackleton is an impact crater that lies at the lunar south pole. The peaks along the crater's rim are exposed to almost continual sunlight, while the interior is perpetually in shadow. The low-temperature interior of this crater functions as a cold trap that may capture and freeze volatiles shed during comet impacts on the Moon. Measurements by the Lunar Prospector spacecraft showed higher than normal amounts of hydrogen within the crater, which may indicate the presence of water ice. The crater is named after Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton.

Peary is the closest large lunar impact crater to the lunar north pole. At this latitude the crater interior receives little sunlight, and portions of the southernmost region of the crater floor remain permanently cloaked in shadow. From the Earth the crater appears on the northern lunar limb, and is seen from the side.

Cabeus is a lunar impact crater that is located about 100 km (62 mi) from the south pole of the Moon. At this location the crater is seen obliquely from Earth, and it is almost perpetually in deep shadow due to lack of sunlight. Hence, not much detail can be seen of this crater, even from orbit. Through a telescope, this crater appears near the southern limb of the Moon, to the west of the crater Malapert and to the south-southwest of Newton.

A peak of eternal light (PEL) is a hypothetical point on the surface of an astronomical body that is always in sunlight. Such a peak must have high latitude, high elevation, and be on a body with very small axial tilt. The existence of such peaks was first postulated by Beer and Mädler in 1837. The pair said about the lunar polar mountains: "...many of these peaks have eternal sunshine". These polar peaks were later mentioned by Camille Flammarion in 1879, who speculated that there may exist pics de lumière éternelle at the poles of the Moon. PELs would be advantageous for space exploration and colonization due to the ability of an electrical device located there to receive solar power regardless of the time of day or day of the year, and the relatively stable temperature range.

Shoemaker is a lunar impact crater located near the southern pole of the Moon, within half a crater diameter of Shackleton.

Faustini is a lunar impact crater that lies near the south pole of the Moon. It is located nearly due south of the much larger crater Amundsen, and is almost attached to Shoemaker to the southwest. About one crater diameter due south is the smaller crater Shackleton at the south pole. A small crater is attached to the eastern rim of Faustini.

Lunar water is water that is present on the Moon. Diffuse water molecules in low concentrations can persist at the Moon's sunlit surface, as discovered by the SOFIA observatory in 2020. Gradually, water vapor is decomposed by sunlight, leaving hydrogen and oxygen lost to outer space. Scientists have found water ice in the cold, permanently shadowed craters at the Moon's poles. Water molecules are also present in the extremely thin lunar atmosphere.

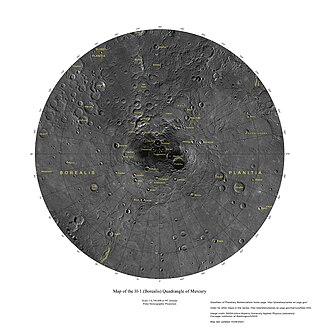

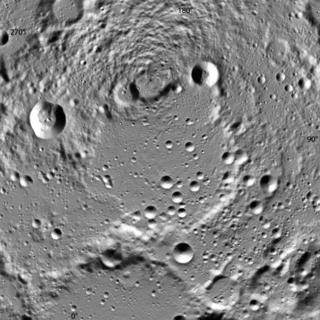

Chao Meng-Fu is a 167 km (104 mi) diameter crater on Mercury named after the Chinese painter and calligrapher Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322). Due to its location near Mercury's south pole and the planet's small axial tilt, an estimated 40% of the crater lies in permanent shadow. This combined with bright radar echoes from the location of the crater leads scientists to suspect that it may shelter large quantities of ice protected against sublimation into the near-vacuum by the constant −171 °C (−276 °F) temperatures.

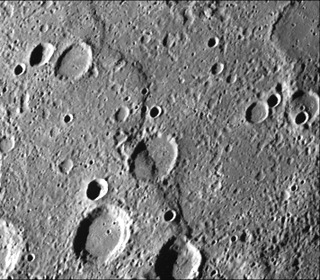

The geology of Mercury is the scientific study of the surface, crust, and interior of the planet Mercury. It emphasizes the composition, structure, history, and physical processes that shape the planet. It is analogous to the field of terrestrial geology. In planetary science, the term geology is used in its broadest sense to mean the study of the solid parts of planets and moons. The term incorporates aspects of geophysics, geochemistry, mineralogy, geodesy, and cartography.

A cold trap is a concept in planetary sciences that describes an area cold enough to freeze (trap) volatiles. Cold-traps can exist on the surfaces of airless bodies or in the upper layers of an adiabatic atmosphere. On airless bodies, the ices trapped inside cold-traps can potentially remain there for geologic time periods, allowing us a glimpse into the primordial solar system. In adiabatic atmospheres, cold-traps prevent volatiles from escaping the atmosphere into space.

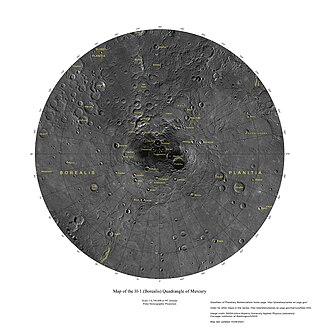

The Borealis quadrangle is a quadrangle on Mercury surrounding the north pole down to 65° latitude. It was mapped in its entirety by the MESSENGER spacecraft, which orbited the planet from 2008 to 2015, excluding areas of permanent shadow near the north pole. Only approximately 25% of the quadrangle was imaged by the Mariner 10 spacecraft during its flybys in 1974 and 1975. The quadrangle is now called H-1.

The lunar south pole is the southernmost point on the Moon. It is of interest to scientists because of the occurrence of water ice in permanently shadowed areas around it. The lunar south pole region features craters that are unique in that the near-constant sunlight does not reach their interior. Such craters are cold traps that contain a fossil record of hydrogen, water ice, and other volatiles dating from the early Solar System. In contrast, the lunar north pole region exhibits a much lower quantity of similarly sheltered craters.

A permanently shadowed crater is a depression on a body in the Solar System within which lies a point that is always in darkness.

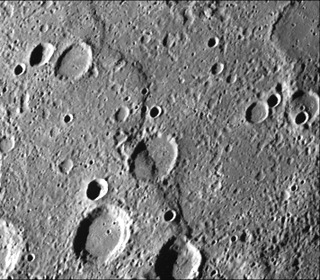

Inter-crater plains on Mercury are a land-form consisting of plains between craters on Mercury.

The Moon bears substantial natural resources which could be exploited in the future. Potential lunar resources may encompass processable materials such as volatiles and minerals, along with geologic structures such as lava tubes that, together, might enable lunar habitation. The use of resources on the Moon may provide a means of reducing the cost and risk of lunar exploration and beyond.