The Flathead Indian Reservation, located in western Montana on the Flathead River, is home to the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles tribes – also known as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. The reservation was created through the July 16, 1855, Treaty of Hellgate.

The Pend Oreille River is a tributary of the Columbia River, approximately 130 miles (209 km) long, in northern Idaho and northeastern Washington in the United States, as well as southeastern British Columbia in Canada. In its passage through British Columbia its name is spelled Pend-d'Oreille River. It drains a scenic area of the Rocky Mountains along the U.S.-Canada border on the east side of the Columbia. The river is sometimes defined as the lower part of the Clark Fork, which rises in western Montana. The river drains an area of 66,800 square kilometres (25,792 sq mi), mostly through the Clark Fork and its tributaries in western Montana and including a portion of the Flathead River in southeastern British Columbia. The full drainage basin of the river and its tributaries accounts for 43% of the entire Columbia River Basin above the confluence with the Columbia. The total area of the Pend Oreille basin is just under 10% of the entire 258,000-square-mile (670,000 km2) Columbia Basin. Box Canyon Dam is currently underway on a multimillion-dollar project for a fish ladder.

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation are a federally recognized tribe in the U.S. state of Montana. The government includes members of several Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles tribes and is centered on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

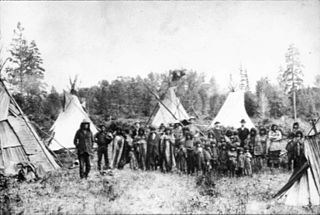

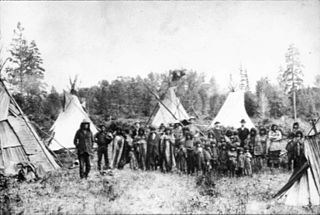

The Bitterroot Salish are a Salish-speaking group of Native Americans, and one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana. The Flathead Reservation is home to the Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles tribes also. Bitterroot Salish or Flathead originally lived in an area west of Billings, Montana extending to the continental divide in the west and south of Great Falls, Montana extending to the Montana-Wyoming border. From there they later moved west into the Bitterroot Valley. By request, a Catholic mission was built here in 1841. In 1891 they were forcibly moved to the Flathead Reservation.

The Kutenai, also known as the Ktunaxa, Ksanka, Kootenay and Kootenai, are an indigenous people of Canada and the United States. Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, northern Idaho, and western Montana. The Kutenai language is a language isolate, thus unrelated to the languages of neighboring peoples or any other known language.

The Pend d’Oreille, also known as the Kalispel, are Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau. Today many of them live in Montana and eastern Washington. The Kalispel peoples referred to their primary tribal range as Kaniksu.

The Bitterroot Valley is located in southwestern Montana, along the Bitterroot River between the Bitterroot Range and Sapphire Mountains, in the Northwestern United States.

The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho is a federally recognized tribe of Lower Kootenai people, sometimes called the Idaho Ksanka. The Ktunaxa, also known as Kutenai, Kootenay and Kootenai are an Indigenous people of the Northwest Plateau.

Salish Kootenai College (SKC) is a Private tribal land-grant community college in Pablo, Montana. It serves the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles tribes. SKC's main campus is on the Flathead Reservation. There are three satellite locations in eastern Washington state, in Colville, Spokane, and Wellpinit. Approximately 1,207 students attend SKC. Although enrollment is not limited to Native American students, SKC's primary function is to serve the needs of Native American people.

Charlo was head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870 to 1910. Charlo followed a policy of peace with the American settlers in Southwestern Montana and with the soldiers at nearby Fort Missoula.

Antonio or Anthony Ravalli was an Italian Jesuit missionary, artist, and doctor active in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. He is known primarily for his contributions to the architecture and art of Jesuit missions in the region. He also inoculated the tribes he served against smallpox, and his efforts shielded the Bitterroot Salish against epidemics that devastated other tribes. In 1893 Ravalli County, Montana was named after him.

The Salish or Séliš language, also known as Kalispel–Pend d'oreille, Kalispel–Spokane–Flathead, or, to distinguish it from the Salish language family to which it gave its name, Montana Salish, is a Salishan language spoken by about 64 elders of the Flathead Nation in north central Montana and of the Kalispel Indian Reservation in northeastern Washington state, and by another 50 elders of the Spokane Indian Reservation of Washington. As of 2012, Salish is "critically endangered" in Montana and Idaho according to UNESCO.

Hell Gate is a ghost town at the western end of the Missoula Valley in Missoula County, Montana, United States. The town was located on the banks of the Clark Fork River roughly five miles downstream from present-day Missoula near what is now Frenchtown.

The Historic St. Mary's Mission is a mission established by the Society of Jesus of the Catholic Church, located now on Fourth Street in modern-day Stevensville, Montana. Founded in 1841 and designed as an ongoing village for Catholic Salish Indians, St. Mary's was the first permanent settlement made by non-indigenous peoples in what became the state of Montana. The mission structure was rebuilt in 1866. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Corwin "Corky" Clairmont is a printmaker and conceptual and installation artist from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. Known for his high concept and politically charged works, Clairmont seeks to explore situations that affect Indian Country historically and in contemporary times.

I don't put work out that gives solutions but provokes questions. - Corky Clairmont

The Swan Valley Massacre was an incident in 1908 in which four Pend d'Oreilles Indians, members of an eight-person hunting party, were killed by a state game warden and his deputy in the Swan Valley in northwestern Montana. The state of Montana did not honor off-reservation hunting permits, although the hunting right was established by federal treaty. The game warden confronted the Pend d'Oreilles party and a gunfight ensued.

The history of Missoula, Montana begins as early as 12,000 years ago with the end of the region's glacial lake period with western exploration dating back to the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806. The first permanent settlement was founded in 1860.

Capt. Christopher Powers Higgins was an American Army captain and later businessman who with Frank Worden founded the Hellgate Trading Post and the nearby city of Missoula, Montana. He erected one of the first lumber and flouring mills on the Clark Fork River near present Downtown Missoula as well as many of Missoula's first buildings and establishments. He was one of the original county commissioners, member of first legislature of the Montana Territory, and incorporator of The Montana Historical Society. Higgins Avenue and bridge as well as the Higgins block in Downtown Missoula are named after him. He is buried in Missoula Cemetery.

Council Grove State Park is a history-oriented, public recreation area located eight miles (13 km) northwest of Missoula in Missoula County, Montana. The site of the park hosted the signing on July 16, 1855, of the Hellgate treaty between representatives of the United States government and members of the Bitterroot Salish, Pend d'Oreille, and the Kootenai to create the Flathead Indian Reservation. A monument commemorates the signing. The park is 187 acres (76 ha) and sits at an elevation of 3,198 feet (975 m). Natural features found in the park are its large, old-growth ponderosa pines, grassy fields, and cottonwood stand by the Clark Fork River. Its recreational features include hiking and fishing.

A number of different Native Americans living in present-day Montana entered into treaties with the United States during the 19th Century. Most of the treaties included an article that established the territory of the tribe entering into it. More and more of this Indian land turned into public or U.S. territory with the signing of new treaties..