Arsenic is a chemical element; it has symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, but only the grey form, which has a metallic appearance, is important to industry.

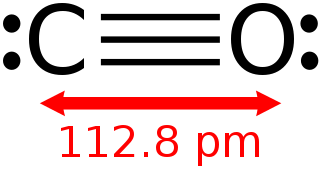

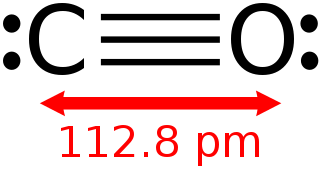

Carbon monoxide is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simplest carbon oxide. In coordination complexes, the carbon monoxide ligand is called carbonyl. It is a key ingredient in many processes in industrial chemistry.

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula NO−

3. Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insoluble nitrate is bismuth oxynitrate.

A toxic heavy metal is any relatively dense metal or metalloid that is noted for its potential toxicity, especially in environmental contexts. The term has particular application to cadmium, mercury and lead, all of which appear in the World Health Organization's list of 10 chemicals of major public concern. Other examples include manganese, chromium, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, silver, antimony and thallium.

A poison is any chemical substance that is harmful or lethal to living organisms. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broad sense.

Arsenic poisoning is a medical condition that occurs due to elevated levels of arsenic in the body. If arsenic poisoning occurs over a brief period of time, symptoms may include vomiting, abdominal pain, encephalopathy, and watery diarrhea that contains blood. Long-term exposure can result in thickening of the skin, darker skin, abdominal pain, diarrhea, heart disease, numbness, and cancer.

A trace element is a chemical element of a minute quantity, a trace amount, especially used in referring to a micronutrient, but is also used to refer to minor elements in the composition of a rock, or other chemical substance.

Trace metals are the metals subset of trace elements; that is, metals normally present in small but measurable amounts in animal and plant cells and tissues and that are a necessary part of nutrition and physiology. Some biometals are trace metals. Ingestion of, or exposure to, excessive quantities can be toxic. However, insufficient plasma or tissue levels of certain trace metals can cause pathology, as is the case with iron.

Lead poisoning, also known as plumbism and saturnism, is a type of metal poisoning caused by lead in the body. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, irritability, memory problems, infertility, and tingling in the hands and feet. It causes almost 10% of intellectual disability of otherwise unknown cause and can result in behavioral problems. Some of the effects are permanent. In severe cases, anemia, seizures, coma, or death may occur.

Mercury poisoning is a type of metal poisoning due to exposure to mercury. Symptoms depend upon the type, dose, method, and duration of exposure. They may include muscle weakness, poor coordination, numbness in the hands and feet, skin rashes, anxiety, memory problems, trouble speaking, trouble hearing, or trouble seeing. High-level exposure to methylmercury is known as Minamata disease. Methylmercury exposure in children may result in acrodynia in which the skin becomes pink and peels. Long-term complications may include kidney problems and decreased intelligence. The effects of long-term low-dose exposure to methylmercury are unclear.

Chelation therapy is a medical procedure that involves the administration of chelating agents to remove heavy metals from the body. Chelation therapy has a long history of use in clinical toxicology and remains in use for some very specific medical treatments, although it is administered under very careful medical supervision due to various inherent risks, including the mobilization of mercury and other metals through the brain and other parts of the body by the use of weak chelating agents that unbind with metals before elimination, exacerbating existing damage. To avoid mobilization, some practitioners of chelation use strong chelators, such as selenium, taken at low doses over a long period of time.

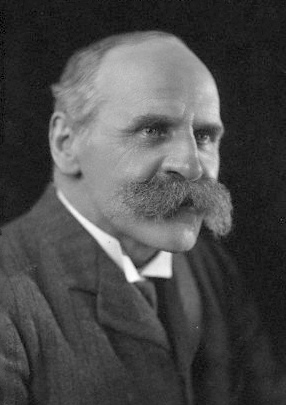

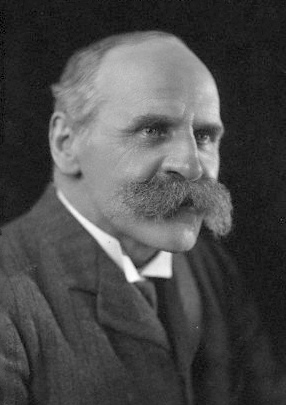

John Scott Haldane was a British physician physiologist and philosopher famous for intrepid self-experimentation which led to many important discoveries about the human body and the nature of gases. He also experimented on his son, the celebrated and polymathic biologist J. B. S. Haldane, even when he was quite young. Haldane locked himself in sealed chambers breathing potentially lethal cocktails of gases while recording their effect on his mind and body.

Metal toxicity or metal poisoning is the toxic effect of certain metals in certain forms and doses on life. Some metals are toxic when they form poisonous soluble compounds. Certain metals have no biological role, i.e. are not essential minerals, or are toxic when in a certain form. In the case of lead, any measurable amount may have negative health effects. It is often thought that only heavy metals can be toxic, but lighter metals such as beryllium and lithium may also be in certain circumstances. Not all heavy metals are particularly toxic, and some are essential, such as iron. The definition may also include trace elements when abnormally high doses may be toxic. An option for treatment of metal poisoning may be chelation therapy, a technique involving the administration of chelation agents to remove metals from the body.

Environmental toxicology is a multidisciplinary field of science concerned with the study of the harmful effects of various chemical, biological and physical agents on living organisms. Ecotoxicology is a subdiscipline of environmental toxicology concerned with studying the harmful effects of toxicants at the population and ecosystem levels.

The health of domestic cats is a well studied area in veterinary medicine.

The presence of mercury in fish is a health concern for people who eat them, especially for women who are or may become pregnant, nursing mothers, and young children. Fish and shellfish concentrate mercury in their bodies, often in the form of methylmercury, a highly toxic organomercury compound. This element is known to bioaccumulate in humans, so bioaccumulation in seafood carries over into human populations, where it can result in mercury poisoning. Mercury is dangerous to both natural ecosystems and humans because it is a metal known to be highly toxic, especially due to its neurotoxic ability to damage the central nervous system.

Salt consumption has been extensively studied for its role in human physiology and impact on human health. Chronic, high intake of dietary salt consumption is associated with hypertension and cardiovascular disease, in addition to other adverse health outcomes. Major health and scientific organizations, such as the World Health Organization, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and American Heart Association, have established high salt consumption as a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and stroke.

John David Spence is a Canadian medical doctor, medical researcher and Professor Emeritus at the University of Western Ontario. He is affiliated with the University of Western Ontario and the Robarts Research Institute, one of Canada's leading medical research organizations. Before his retirement from clinical practice in July 2022, he was also affiliated with the London Health Sciences Centre's University Hospital. He is a recognized expert in stroke prevention and stroke prevention research, with more than 600 peer-reviewed publications since 1970. He delivered more than 600 lectures on stroke prevention in 42 countries. In 2015, he received the Research Excellence Award from the Canadian Society for Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. In 2019, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada, and in 2020 he received the William Feinberg Award from the American Heart Association for excellence in clinical stroke research.

Alexander Haig was a Scottish physician, dietitian and vegetarianism activist. He was best known for pioneering the uric-acid free diet.

Jerome Okon Nriagu is a Nigerian-born, American environmental chemist, academician and researcher. He is Professor Emeritus in the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan. He was formerly a Research Scientist at Environment Canada in the former National Water Research Institute, Burlington, Ontario, and an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Waterloo, Canada.