Related Research Articles

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in such a manner is known as a death sentence, and the act of carrying out the sentence is known as an execution. A prisoner who has been sentenced to death and awaits execution is condemned and is commonly referred to as being "on death row". Etymologically, the term capital refers to execution by beheading, but executions are carried out by many methods, including hanging, shooting, lethal injection, stoning, electrocution, and gassing.

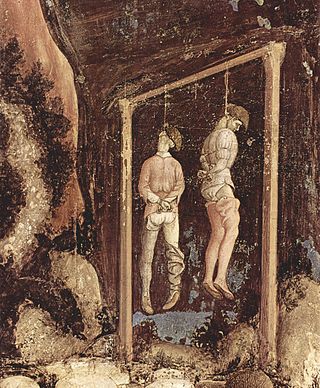

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerous countries and regions. The first known account of execution by hanging is in Homer's Odyssey. Hanging is also a method of suicide.

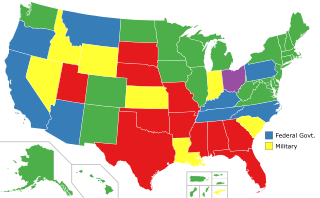

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty in 27 states, throughout the country at the federal level, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in the other 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 20 of them have authority to execute death sentences, with the other 7, as well as the federal government and military, subject to moratoriums.

Capital punishment in traditional Jewish law has been defined in Codes of Jewish law dating back to medieval times, based on a system of oral laws contained in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmud, the primary source being the Hebrew Bible. In traditional Jewish law there are four types of capital punishment: a) stoning, b) burning by ingesting molten lead, c) strangling, and d) beheading, each being the punishment for specific offenses. Except in special cases where a king can issue the death penalty, capital punishment in Jewish law cannot be decreed upon a person unless there were a minimum of twenty-three judges (Sanhedrin) adjudicating in that person's trial who, by a majority vote, gave the death sentence, and where there had been at least two competent witnesses who testified before the court that they had seen the litigant commit the offense. Even so, capital punishment does not begin in Jewish law until the court adjudicating in this case had issued the death sentence from a specific place on the Temple Mount in the city of Jerusalem.

The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) states that it is "the largest Arab American grassroots civil rights organization in the United States." According to its webpage, it is open to people of all backgrounds, faiths and ethnicities and has a national network of chapters and members in all 50 states. It claims that three million Americans trace their roots to an Arab country.

The National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP) is an organization dedicated to the abolition of the death penalty in the United States. Founded in 1976 by Henry Schwarzschild, the NCADP is the only fully staffed nationwide organization in the United States dedicated to the total abolition of the death penalty. It also provides extensive information regarding imminent and past executions, death penalty defendants, numbers of people executed in the U.S., as well as a detailed breakdown of the current death row population, and a list of which U.S. state and federal jurisdictions use the death penalty.

The major world religions have taken varied positions on the morality of capital punishment and, as such, they have historically impacted the way in which governments handle such punishment practices. Although the viewpoints of some religions have changed over time, their influence on capital punishment generally depends on the existence of a religious moral code and how closely religion influences the government. Religious moral codes are often based on a body of teachings, such as the Old Testament or the Qur'an.

Charles Lund Black Jr. was an American scholar of constitutional law, which he taught as professor of law from 1947 to 1999. He is best known for his role in the historic Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case, as well as for his Impeachment: A Handbook, which served for many Americans as a trustworthy analysis of the law of impeachment during the Watergate scandal.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Israel. Capital punishment has only been imposed twice in the history of the state and is only to be handed out for treason, genocide, crimes against humanity, and crimes against the Jewish people during wartime. Israel is one of seven countries to have abolished capital punishment for "ordinary crimes only."

The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) is a civil rights organization in the United States. Founded in November 1951 as the New York affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, it is a not-for-profit, nonpartisan organization with nearly 50,000 members across New York State.

Stephen B. Bright is an American lawyer known for representing people facing the death penalty, advocating for the right to counsel for poor people accused of crimes, and challenging inhumane practices and conditions in prisons and jails. He has taught at Yale Law School since 1993 and has been teaching at the Georgetown Law Center since 2017. In 2016, he ended almost 35 years at the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, first as director from 1982 to 2005, and then as president and senior counsel from 2006 to 2016.

The Canadian Coalition Against the Death Penalty (CCADP) is a not-for-profit organization which was co-founded by Tracy Lamourie and Dave Parkinson of the Greater Toronto Area. The couple formed the CCADP to speak out against the use of capital punishment around the world, to educate and encourage fellow Canadians to resist the occasional calls for a renewal of the death penalty within their own country, and to urge the Canadian government to ensure fair trials and appeals, as well as adequate legal representation, for Canadians convicted of crimes abroad. The CCADP website also quickly evolved into a space where death row inmates and their supporters could post their stories and seek contact with the outside world.

Palestinian land laws dictate how Palestinians are to handle their ownership of land under the Palestinian National Authority—currently only in the West Bank. Most notably, these laws prohibit Palestinians from selling any Palestinian-owned lands to "any man or judicial body corporation of Israeli citizenship, living in Israel or acting on its behalf". These land laws were originally enacted during the Jordanian occupation of the West Bank, which began after Jordan's partial victory during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and ended after the sweeping defeat of the Arab coalition to the Israeli military during the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, following which the territory was occupied by Israel. Land sales by Palestinians to Israelis are considered treasonous by the former to the Palestinian national cause because they threaten the aspiration for an independent Palestinian state. The prohibition on land-selling to Israelis in these laws is also stated as enforced in order to "halt the spread of moral, political and security corruption". Consequently, Palestinians who sell land to Israelis can be sentenced to death under Palestinian governance, although death penalties are seldom carried out; capital punishment has to be approved by the President of the Palestinian National Authority.

William Anthony Schabas, OC is a Canadian academic specialising in international criminal and human rights law. He is professor of international law at Middlesex University in the United Kingdom, professor of international human law and human rights at Leiden University in the Netherlands, and an internationally respected expert on human rights law, genocide and the death penalty.

The debate over capital punishment in the United States existed as early as the colonial period. As of April 2022, it remains a legal penalty within 28 states, the federal government, and military criminal justice systems. The states of Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, New Hampshire, Virginia, and Washington abolished the death penalty within the last decade alone.

Capital punishment is legal in most countries of the Middle East. Much of the motivation for the retention of the death penalty has been religious in nature, as the Qur'an allows or mandates executions for various offences.

The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights is a Palestinian human rights organization based in Gaza City. It was founded in 1995 by Raji Sourani, who is its director. It was established by a group of Palestinian lawyers and human rights activists and receives funding from governmental, non-governmental, and religious sources.

Capital punishment in Sudan is legal under Article 27 of the Sudanese Criminal Act 1991. The Act is based on Sharia law which prescribes both the death penalty and corporal punishment, such as amputation. Sudan has moderate execution rates, ranking 8th overall in 2014 when compared to other countries that still continue the practice, after at least 29 executions were reported.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Uganda. The death penalty was likely last carried out in 1999, although some sources say the last execution in Uganda took place in 2005. Regardless, Uganda is interchangeably considered a retentionist state with regard to capital punishment, due to absence of "an established practice or policy against carrying out executions," as well as a de facto abolitionist state due to the lack of any executions for over one decade.

Ethiopia retains capital punishment while not ratified the Second Optional Protocol (ICCR) of UN General Assembly resolution. Historically, capital punishments was codified under Fetha Negest in order to fulfill societal desire. Death penalty can be applied through approval of the President, but executions are rare.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pace, Eric (1996-06-04), "Henry Schwarzschild, 70, Opponent of Death Penalty.", New York Times, retrieved 2009-03-03

- ↑ Haines, Herbert H. (1996). Against capital punishment : the anti-death penalty movement in America, 1972-1994. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0195088387.

- ↑ Haines 1996, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ball, Milner S. (1993), The Word and the Law, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-03625-0

- ↑ Civil Rights Digital Library "Henry Schwarzschild", Digital Library of Georgia, 2009, retrieved 2009-04-06[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ "Oral history interview with Henry Schwarzschild, 1992". DLC Catalog. Retrieved 2024-07-16.

- ↑ Handler, M. S. “Lawyers Corps Is Formed Here To Aid Rights Drive in the South.” The New York Times, 21 May 1964, p. 26. Accessed 22 June 2024.

- 1 2 Haines, Herbert (1996), "The Anti-Death Penalty movement in America, 1972-1994" , Against Capital Punishment, New York: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oso/9780195088380.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-508838-0

- ↑ Learn More, NCADP, 2009, archived from the original on 2009-04-29, retrieved 2009-04-07

- ↑ "Henry Schwarzschild Award | The Jewish Press - JewishPress.com" . Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ↑ "Tag: Henry Schwarzschild Award". www.jewishpress.com.

- ↑ Shedd/Schwarzschild Abraham Lincoln Collection, Berea College Books and Printed Sources, 2009

- 1 2 Henry Schwarzschild Lecture, NYCLU Lower Hudson Valley Chapter, 2009, retrieved 2009-04-06[ permanent dead link ]

- General

- Bedau, Hugo (1997), "Current Controversies" , Death Penalty in America, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-502987-1