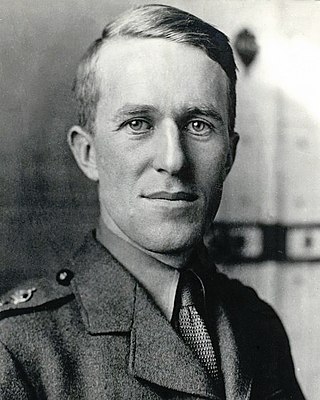

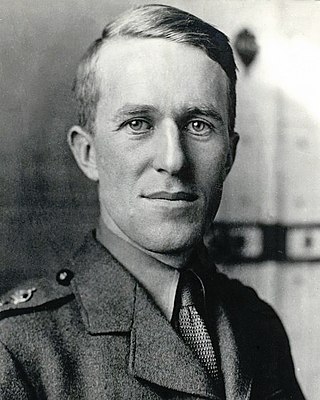

Thomas Edward Lawrence was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918) against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. The breadth and variety of his activities and associations, and his ability to describe them vividly in writing, earned him international fame as Lawrence of Arabia, a title used for the 1962 film based on his wartime activities.

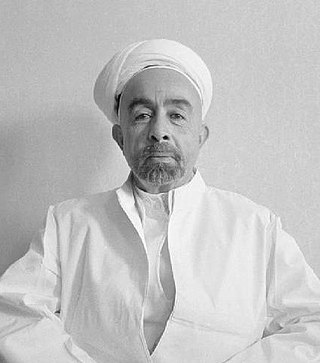

Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi was King of Iraq from 23 August 1921 until his death in 1933. A member of the Hashemite family, he was a leader of the Great Arab Revolt during the First World War, and ruled as the unrecognized King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria from March to July 1920 when he was expelled by the French.

The Hashemites, also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921–1958). The family had ruled the city of Mecca continuously from the 10th century, frequently as vassals of outside powers, and ruled the thrones of the Hejaz, Syria, Iraq, and Jordan following their World War I alliance with the British Empire.

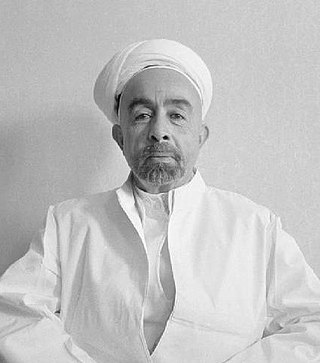

Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein was the ruler of Jordan from 11 April 1921 until his assassination in 1951. He was the Emir of Transjordan, a British protectorate, until 25 May 1946, after which he was king of an independent Jordan. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family of Jordan since 1921, Abdullah was a 38th-generation direct descendant of Muhammad.

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led the British Empire's Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign against the Ottoman Empire in the conquest of Palestine.

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I in which the Government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca launching the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The correspondence had a significant influence on Middle Eastern history during and after the war; a dispute over Palestine continued thereafter.

The Arab Revolt, also known as the Great Arab Revolt, was an armed uprising by the Hashemite-led Arabs of the Hejaz against the Ottoman Empire amidst the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

The Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz was a state in the Hejaz region of Western Asia that included the western portion of the Arabian Peninsula that was ruled by the Hashemite dynasty. It was self-proclaimed as a kingdom in June 1916 during the First World War, to be independent from the Ottoman Empire, on the basis of an alliance with the British Empire to drive the Ottoman Army from the Arabian Peninsula during the Arab Revolt.

The Arab Bureau was a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department established in 1916 during the First World War, and closed in 1920, whose purpose was the collection and dissemination of propaganda and intelligence about the Arab regions of the Middle East.

The Damascus Protocol was a document given to Faisal bin Hussein on 23 May 1915 by the Arab secret societies al-Fatat and al-'Ahd on his second visit to Damascus during a mission to consult Turkish officials in Constantinople.

The Sharifian Army, also known as the Arab Army, or the Hejazi Army was the military force behind the Arab Revolt which was a part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. Sharif Hussein Ibn Ali of the Kingdom of Hejaz, who was proclaimed "Sultan of the Arabs" in 1916, led the Sharifian Army in a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire with the ultimate goal of uniting the Arab people under an independent government. Aided both financially and militarily by the British, Husayn's forces gradually moved north through the Hejaz and, fought alongside the British-controlled Egyptian Expeditionary Force, eventually capturing Damascus. Once there, members of the Sharifian Army set up a short-lived monarchy known as the Arab Kingdom of Syria led by Faisal, a son of Sharif Husayn.

Sir Ronald Henry Amherst Storrs was an official in the British Foreign Office. He served as Oriental Secretary in Cairo, Military Governor of Jerusalem, Governor of Cyprus, and Governor of Northern Rhodesia.

Brigadier-General Sir Wyndham Henry Deedes, was a British Army officer and civil administrator. He was the Chief Secretary to the British High Commissioner of the British Mandate of Palestine.

Brigadier-General Sir Gilbert Falkingham Clayton was a British Army intelligence officer and colonial administrator, who worked in several countries in the Middle East in the early 20th century. In Egypt, during World War I as an intelligence officer, he supervised those who worked to start the Arab Revolt. In Palestine, Arabia and Mesopotamia, in the 1920s as a colonial administrator, he helped negotiate the borders of the countries that later became Israel, Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

Lt Col. Stewart Francis Newcombe (1878–1956) was a British army officer and associate of T. E. Lawrence.

This is a timeline of major events in the history of the modern state of Jordan.

Robert Vere Buxton, known as Robin Buxton, was an English cricketer, soldier and banker.

The Garland grenade was a grenade and trench mortar bomb developed and used by British Empire forces in the First World War. It was invented by the metallurgist Herbert Garland at the Cairo Citadel, and more than 174,000 were issued to the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. The grenade was also used during the Arab Revolt. The Mark I grenade was relatively primitive, being formed of an explosive-filled food tin with a fuse that was lit with a match. The Mark II version was made of cast iron and could be fired from the Garland Trench Mortar.

Al Qibla was the official gazette of the Kingdom of Hejaz. The paper was backed by the British. It was in circulation between 1916 and 1924 and headquartered in Mecca. The paper was a four-page broadsheet and published twice a week, on Mondays and on Thursdays.

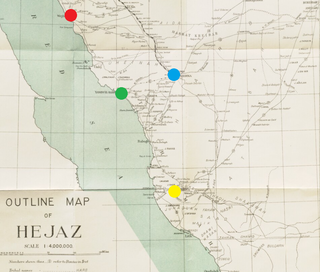

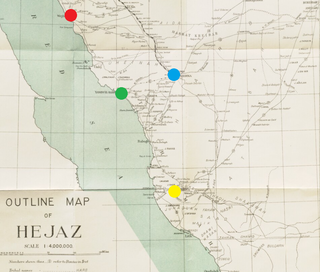

The capture of Wejh took place on 23–24 January 1917 when British-led Arab forces landed by sea and, with the support of naval bombardments, defeated the Ottoman garrison. The attack was intended to threaten the flanks of an Ottoman advance from their garrison in Medina to Mecca, which had been captured by Arab forces in 1916. The sea-based force was to have attacked in co-operation with a larger force under Arab leader Faisal but these men were held up after capturing a quantity of supplies and gold en-route to Wejh. The sea-based force under Royal Navy leadership captured Wejh with naval artillery support, defeating the 1,300-strong Ottoman garrison. The capture of the town safeguarded Mecca, as the Ottoman troops were withdrawn to static defence duties in and around Medina.