Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole was a prince of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi until it was overthrown by a coalition of American and European businessmen in 1893. He later went on to become a representative in the Territory of Hawaii as delegate to the United States Congress, and as such is the only royal-born member of Congress.

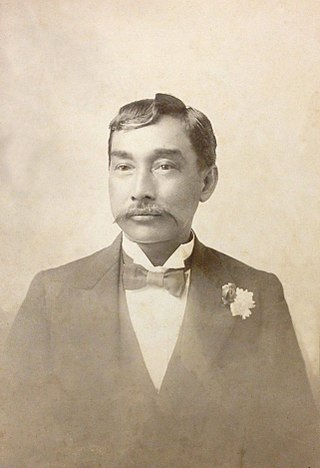

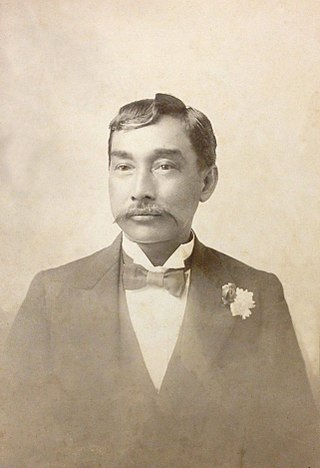

David Laʻamea Kahalepouli Kinoiki Kawānanakoa was a prince of the Hawaiian Kingdom and founder of the House of Kawānanakoa. Born into Hawaiian nobility, Kawānanakoa grew up the royal court of his uncle King Kalākaua and aunt Queen Kapiʻolani who adopted him and his brothers after the death of their parents. On multiple occasions, he and his brothers were considered as candidates for the line of succession to the Hawaiian throne after their cousin Princess Kaʻiulani but were never constitutionally proclaimed. He was sent to be educated abroad in the United States and the United Kingdom where he pioneered the sport of surfing. After his education abroad, he served as a political advisor to Kalākaua's successor, Queen Liliʻuokalani until the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893. After Hawaii's annexation to the United States, he co-founded the Democratic Party of Hawaii.

The following is an alphabetical list of articles related to the U.S. state of Hawaii:

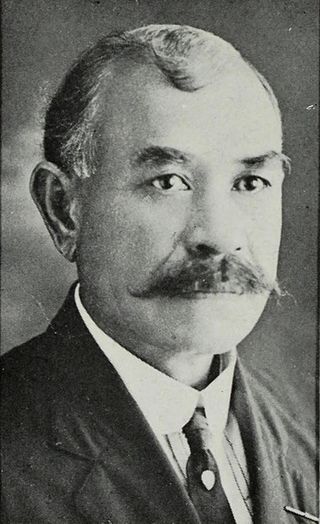

Robert William Kalanihiapo Wilcox, nicknamed the Iron Duke of Hawaiʻi, was a Native Hawaiian whose father was an American and whose mother was Hawaiian. A revolutionary soldier and politician, he led uprisings against both the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom under King Kalākaua and the Republic of Hawaii under Sanford Dole, what are now known as the Wilcox rebellions. He was later elected the first delegate to the United States Congress for the Territory of Hawaii.

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii out of a desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-governance.

The Hawaii Republican Party is the affiliate of the Republican Party (GOP) in Hawaii, headquartered in Honolulu. The party was strong during Hawaii's territorial days, but following the Hawaii Democratic Revolution of 1954 the Democratic Party came to dominate Hawaii. The party currently has little power and is the weakest state affiliate of the national Republican Party; it controls none of Hawaii's statewide or federal elected offices and has the least presence in the state legislature of any state Republican party.

Joseph Kahoʻoluhi Nāwahī, also known by his full Hawaiian name Iosepa Kahoʻoluhi Nāwahīokalaniʻōpuʻu, was a Native Hawaiian nationalist leader, legislator, lawyer, newspaper publisher, and painter. Through his long political service during the monarchy and the important roles he played in the resistance and opposition to its overthrow, Nāwahī is regarded as an influential Hawaiian patriot.

The Honourable John Mahi'ai Kāneakua was a noble of the non-ruling elite of the Kingdom of Hawaii, an attorney and politician. He was re-elected to the position of County Clerk of Kaua‘i for 28 years until his retirement at the age of 74.

Joseph Hewahewa Kaimihakulani Heleluhe was a member of the Hawaiian nobility who served as a retainer and private secretary of Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and accompanied her on her trips to the United States and Washington, D.C., from 1896 to 1900 to prevent the American annexation of Hawaii.

William Pūnohuʻāweoweoʻulaokalani White was a Hawaiian lawyer, sheriff, politician, and newspaper editor. He became a political statesman and orator during the final years of the Kingdom of Hawaii and the beginnings of the Territory of Hawaii. Despite being a leading Native Hawaiian politician in this era, his legacy has been largely forgotten or portrayed in a negative light, mainly because of a reliance on English-language sources to write Hawaiian history. He was known by the nickname of "Pila Aila" or "Bila Aila" for his oratory skills.

Joseph Apukai Akina was a lawyer, politician and minister of the Kingdom of Hawaii and later Territory of Hawaii. He served as a statesman during the reign of Queen Liliʻuokalani and later became the first Speaker of the House of Representatives in the Hawaii Territorial Legislature.

John Henry Wise was a Native Hawaiian politician, businessman, religious leader, and educator of Hawaii. In his youth, he became the first Native Hawaiian to play college football with the Oberlin Yeomen football team while he attended theology school at Oberlin College. During his political career in the Hawaii Territorial Legislature, he helped pass the Hawaiian Homelands Act of 1921. In later life, he served as an instructor of Hawaiian language at the Kamehameha Schools and the University of Hawaii.

Samuel Kaholoʻokalani Pua was a Native Hawaiian politician, newspaper editor, lawyer and sheriff of Hawaii. He served as a legislator during the last years of the Kingdom of Hawaii and worked as an assistant editor for the anti-annexationist newspaper Ke Ahailono o Hawaii run by members of Hui Kālaiʻāina, after the overthrow of the monarchy. After the annexation, he became a sheriff during the Territory of Hawaii.

Emma ʻAʻima Aʻii Nāwahī was a Native Hawaiian political activist, community leader and newspaper publisher. She and her husband Joseph Nāwahī were leaders in the opposition to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and they co-founded Ke Aloha Aina, a Hawaiian language newspaper, which served as an important voice in the resistance to the annexation of Hawaiʻi to the United States. After annexation, she helped establish the Democratic Party of Hawaiʻi and became a supporter of the women's suffrage movement.

Emilie Kekāuluohi Widemann Macfarlane was a Native Hawaiian activist and civic organizer during the late 19th and early 20th centuries She was known for her charitable work and civic involvement in Honolulu, including women's suffrage, public health, education, and the preservation of Hawaii's historical legacy.

Hui Aloha ʻĀina were two Hawaiian nationalist organizations established by Native Hawaiian political leaders and statesmen and their spouses in the aftermath of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Queen Liliʻuokalani on January 17, 1893. The organization was formed to promote Hawaiian patriotism and independence and oppose the overthrow and the annexation of Hawaii to the United States. Its members organized and collected the Kūʻē Petitions to oppose the annexation, which ultimately blocked a treaty of annexation in the United States Senate in 1897.

The Hui Kālaiʻāina was a political group founded in 1888 to oppose the 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, often known as the Bayonet Constitution, and to promote Native Hawaiian leadership in the government. It and the two organizations of Hui Aloha ʻĀina were active in the opposition to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the annexation of Hawaii to the United States from 1893 to 1898.

The Aloha ʻĀina Party is a political party in the US state of Hawaiʻi that advocates for the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and the promotion of Native Hawaiian culture.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Hawaii. Hawaii went through a transition where it was first the Kingdom of Hawaii, then a political coup overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893. Women were not allowed to vote and lost political power in the provisional government. In the same year as the coup, Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett and Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina began to make plans to support women's suffrage efforts. When Hawaii was annexed, members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) advocated for women's suffrage for the territory. In 1912, Dowsett and a diverse group of women created the National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawaiʻi (WESAH). In 1915 and 1916 Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole brought women's suffrage petitions to the United States Congress, but no action was taken. In 1919, suffragists from WESAH fought for women's suffrage in the territorial legislature, but were also unsuccessful. Women in Hawaii gained the right to vote when the Nineteenth Amendment became part of the United States Constitution on August 26, 1920.

Women's suffrage began in Hawaii in the 1890s. However, when the Hawaiian Kingdom ruled, women had roles in the government and could vote in the House of Nobles. After the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893, women's roles were more restricted. Suffragists, Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett and Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina, immediately began working towards women's suffrage. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) of Hawaii also advocated for women's suffrage in 1894. As Hawaii was being annexed as a US territory in 1899, racist ideas about the ability of Native Hawaiians to rule themselves caused problems with allowing women to vote. Members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) petitioned the United States Congress to allow women's suffrage in Hawaii with no effect. Women's suffrage work picked up in 1912 when Carrie Chapman Catt visited Hawaii. Dowsett created the National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawaiʻi that year and Catt promised to act as the delegate for NAWSA. In 1915 and 1916, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole brought resolutions to the U.S. Congress requesting women's suffrage for Hawaii. While there were high hopes for the effort, it was not successful. In 1919, suffragists around Hawaii met for mass demonstrations to lobby the territorial legislature to pass women's suffrage bills. These were some of the largest women's suffrage demonstrations in Hawaii, but the bills did not pass both houses. Women in Hawaii were eventually franchised through the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.