A hospital chantry is a part of a hospital dedicated to prayer.

A hospital chantry is a part of a hospital dedicated to prayer.

During the period 1100 to 1600 the western Latin Church developed a comprehensive theology of charity and what came to be known as Purgatory. In Scotland together with England and Wales, different traditions developed in the provision of care for the elderly, the sick and the dying.

In Scotland hospitals provided a number of functions: Travellers’ rest, care homes for elderly men and women; and sub-monastic prayer communities. Hospitals such as Bishop Dunbar’s Hospital in Old Aberdeen were in part prayer communities and in part care homes. Most hospitals or maison Dieu had a place or room set aside as a chantry chapel, or an oratory. [lower-alpha 1] In the Kincardine O’Neil Hospital, the situation on a drove road offered a travellers’ rest as well as a care and prayer community. Cowan et al. [1] provide details of some 165 hospitals that offered all or some of these functions. In England, similar conditions from the early to late medieval period applied. [2] [3]

In addition to care for the elderly, the church in Scotland and England became dominated by what might be called a theology of care for the elderly, [lower-alpha 2] The theology and practice of purgatory came to dominate the church and the country as a whole.

Across the Western world charity and purgatory became the two themes that were often in conflict. Bedehouses and hospitals were founded to meet the requirements of charity and purgatory. In response to this theology individuals often made provision for their after-life by endowing priests and others to say what became known as the Requiem Mass.

The chantry became the place where such masses where said. [lower-alpha 3] Chantries owe their name and function of providing an endowment or place for the maintenance of priests to sing daily mass for the souls of founders. [5]

In some cases altars or chapels in churches were endowed in this fashion. [lower-alpha 4]

In Scotland Bishop Dunbar, in the months before he died in 1532, founded a "chantry" or chapel in Elgin Cathedral in memory of his father and mother. The mortification records his wishes and obligations as follows:

…in honorem Sanctse Trinitatis et fanctorum Columbae et Thomae martyris, et pro falute animarum Regis ejufque predeceflbrum et fucceflbrum, Alexandri Dunbar de Weftfeld militis et dominse Elizabethie Suthirland ejus fponfse…" [6]

Howard Colvin [7] provides a definitive account of the origins of chantries in England. Further evidence of their Anglo-Norman origins is provided by David Crouch. [8] Colvin summarizes the situation as follows:

… in origin the chantry can therefore be seen as the answer to what was essentially a monastic problem: how to continue effectively to intercede for an army of the dead whose ranks were already growing uncontrollably even before the official recognition of Purgatory had drawn fresh attention to their predicament. It was a privatised means of salvation devised to cope with an increasing demand for intercession with which the established monastic corporations could not cope … the chantry may well have satisfied, in a way acceptable to the Church, the deep-rooted desire for a religious establishment under private control which, in its grosser forms, had been stamped out by the reforms of the twelfth century. Its flexibility in terms both of endowment and of duration enabled it – unlike the monastic foundation – to be adapted to the means of all ranks of society, so that what had begun largely as a form of seigneurial piety came in time to be adopted by the new squirearchy of the later middle ages and by self-made men like wool-merchants, who could identify with a parish church in a way that they perhaps could not with an old-established monastery of royal or baronial foundation …

In general functions provided in chantries where they were separate establishments – e.g. Noseley, St Anne's Chapel in Barnstaple, Devon and Lincoln Cathedral were the same as those provided in many of the medieval hospitals and bedehouses in Scotland. [lower-alpha 5]

Brechin is a town and former Royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Reformation Roman Catholic diocese, but that status has not been officially recognised in the modern era.

An almshouse is charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the Middle Ages. They were often targeted at the poor of a locality, at those from certain forms of previous employment, or their widows, and at elderly people who could no longer pay rent, and are generally maintained by a charity or the trustees of a bequest. Almshouses were originally formed as extensions of the church system and were later adapted by local officials and authorities.

In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons, a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, headed by a dignitary bearing a title which may vary, such as dean or provost. In its governance and religious observance a collegiate church is similar in some respects to a cathedral, although a collegiate church is not the seat of a bishop and has no diocesan responsibilities. Collegiate churches have often been supported by endowments, including lands, or by tithe income from appropriated benefices. The church building commonly provides both distinct spaces for congregational worship and for the choir offices of the canons.

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

The Diocese of Aberdeen was originally believed to be the direct continuation of an 11th-century bishopric at Mortlach in present-day Moray. However, this early date and also the first bishops were based on a misinterpretation and reliance on early charters found in the cartulary of Aberdeen Cathedral that are now known to be false. The first recorded bishop of the diocese was Nectan, who was mentioned in the Book of Deer around 1132. The first direct written evidence of a bishop in Aberdeen is found in a papal bull addressed to Bishop Edward in 1157. This bull acknowledges the existence of his cathedral, discusses the formation of a chapter, and marks the start of the expansion of the diocesan structure.

Bedesman, or beadsman, was generally a pensioner or almsman whose duty was to pray for his benefactor.

The Bede House in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, is a 17th-century Scottish town house. It was built in 1676 as a residence for Bailie William Logan and his wife Jean Moir of Stoneywood. During the late 18th century, Old Aberdeen Bedesmen moved from their original hospital beside St Machar's Church to the former Logan house in Don Street. In the 19th century the house changed hands. It was first owned by the Burgh of Old Aberdeen, then, by the City of Aberdeen after the merger of the two burghs in 1891. The house was refurbished by the City of Aberdeen Council in 1965. It was divided into two flats or apartments. The flats are now in private ownership. Much of the 17th-century building is in its original form. It is an excellent example of an L-shaped Scottish Town House, built on three floors with an attic. The house is designated as a Category A listed building.

Beggars' badges were badges and other identifying insignia worn by beggars beginning in the early fifteenth century in Great Britain and Ireland. They served two purposes; to identify individual beggars, and to allow beggars to move freely from place to place.

Browne's Hospital is a medieval almshouse in Stamford, Lincolnshire, England. It was founded in 1485 by wealthy wool merchant William Browne to provide a home and a house of prayer for twelve poor men and two poor women.

Mitchell's Hospital, Old Aberdeen, in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, was founded by the philanthropist David Mitchell in 1801 as follows: " .. from a regard for the inhabitants of the city of Old Aberdeen and its ancient college and a desire in these severe times to provide lodging, maintenance and clothing for a few aged relicks and maiden daughters of decayed gentlemen merchants or trade burgesses of the said city.. ". See the text of the 1801 Mortification or the conditions of the endowment. The Hospital is owned and managed by the University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen City Council and the Cathedral Church of St Machar in Old Aberdeen. The origins of the Hospital are due to various attempts by the Incorporated Trades and Merchants in Old Aberdeen to provide a "care home" for their elderly and infirm members and their "relicks".

Bishop Dunbar's Hospital was founded in 1531 by Bishop Gavin Dunbar, the Elder. The hospital was endowed by a mortification just before his death. Dunbar petitioned the King, James V of Scotland, and the charter, signed on 24 February 1531 records the King’s approval that ‘[Dunbar shall] ... found an hospital near the cathedral church, but outside the cemetery...’ It was also known as St Mary's Hospital. In the mortification, Dunbar's charitable purpose is recorded. Bedesmen were supported by a charitable foundation that emerged from the original church control until the twenty-first century. Bedesmen drew their name from the word "bede" - a prayer. The residents of Dunbar's Hospital said prayers in a cycle of Divine Office. The Bede House, Old Aberdeen was used by the Bedesmen from the hospital from 1789 to the end of the nineteenth century. The only remains of the 1531 building can be seen in a perimeter wall for Seaton Park in Old Aberdeen. The last Bedesman died in 1988. The Managers of the Hospital constituted a Charity, Bishop Dunbar Hospital Trust. The Charity ceased active operation in 2012.

Kincardine O'Neil Hospital was founded in the 13th century in the village of Kincardine O'Neil in Scotland. Almost certainly it served as a traveler's inn and as a hospice for elderly and "poor" men. The hospital was situated adjacent to a bridge over the River Dee and may have been a chantry for the early Bishops of Mortlach. Remains of a building can be seen abutted to the Auld Parish Church in Kincardine O'Neil. This building may have been a later or second hospital. It is also possible that these ruins may have been part of St Erchard's Church - a.k.a. St Marys' or the Auld Kirk.

Hospitals in medieval Scotland can be dated back to the 12th century. From c. 1144 to about 1650 many hospitals, bedehouses and maisons Dieu were built in Scotland.

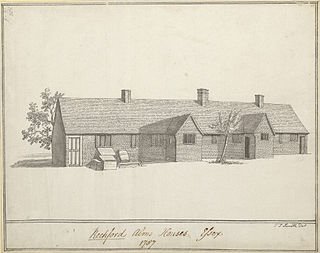

Several Aberdeen trades hospitals were built by the merchants and trades associations of Aberdeen from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. Traditionally hospitals had been built by the church.

Like most cities and towns across Scotland, Aberdeen and its twin city of Old Aberdeen had poorhouses to complement the provision for the poor and need provided by the church, the merchants and the trades. A Poor Hospital was founded in 1741. This replaced the "Correction House" dating from the 1636/7

Across the United Kingdom, many services such as hospitals and schools depend on private or corporate donation. In the sixteenth century,(before 1560 in Scotland) the Church and the nobility were the only source of such support. By the nineteenth century, government and local authorities had taken over this responsibility. Poor Laws in the nineteenth century provided a more secure form of help for the poor and gradually the use of mortifications declined. Sometimes a hospital, Bedehouse, or care home was given money directly to further its purposes. The City of Aberdeen like many across Scotland, and in the rest of the United Kingdom, administers charitable trusts to benefit its residents. Some of these date back to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In general these mortifications were endowed to benefit Guildry members, the poor, medical, educational, cultural, arts and heritage purposes individuals and groups. Recently the City Council has re-organised these charities together with OSCR. Some of the charities have been wound up with residual funds allocated to other charities with similar purposes in Aberdeen.

The Hospital of St John the Baptist, at Arbroath, Scotland, was founded in the early 14th century by the monastic community at Arbroath Abbey. The exact date for the foundation is uncertain, but it is first recorded in 1325 during the time that Bernard of Kilwinning (1324–c.1328) was Abbot of Arbroath. The Abbey itself was founded in 1178 by King William the Lion for a group of Tironensian Benedictine monks from Kelso Abbey. It was consecrated in 1197. It is possible that the hospital was used by travellers, as a chantry or possibly almshouse.

Canon Alexander Galloway was a 16th-century cleric from Aberdeen in Scotland. He was not only a Canon of St Machar's Cathedral, he was a Royal Notary and Diocesan Clerk for James IV and James V of Scotland; vicar of the parishes of Fordyce, Bothelny and Kinkell (1516-1552); five times Rector of King's College – University of Aberdeen; Master of Works on the Bridge of Dee in Aberdeen and for Greyfriars Church in Aberdeen; and Chancellor of the Diocese of Aberdeen. According to Steven Holmes, he was one of the most notable liturgists of his time, designing many fine examples of Sacrament Houses across the North-East of Scotland. He was a friend of and adviser to Hector Boece, the first Principal of the University of Aberdeen, as well as Bishop Elphinstone, Chancellor of Scotland and Gavin Dunbar. He was an avid anti-Reformationist being a friend of Jacobus Latomus and Erasmus and clerics in the Old University of Leuven. Along with Gavin Dunbar, Galloway designed and had built the western towers of the cathedral and designed the heraldic ceiling, featuring 48 coats of arms in three rows of sixteen. More than anyone else he contributed to the development of the artistry of Scottish lettering. He has a claim to be what some might call "a Renaissance Man".

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)