Isaac Watts was an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician. He was a prolific and popular hymn writer and is credited with some 750 hymns. His works include "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross", "Joy to the World", and "O God, Our Help in Ages Past". He is recognised as the "Godfather of English Hymnody"; many of his hymns remain in use today and have been translated into numerous languages.

George Wither was a prolific English poet, pamphleteer, satirist and writer of hymns. Wither's long life spanned one of the most tumultuous periods in the history of England, during the reigns of Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I, the Civil War, the Parliamentary period and the Restoration period.

Christopher Smart was an English poet. He was a major contributor to two popular magazines, The Midwife and The Student, and a friend to influential cultural icons like Samuel Johnson and Henry Fielding. Smart, a high church Anglican, was widely known throughout London.

James Montgomery was a Scottish-born hymn writer, poet and editor, who eventually settled in Sheffield. He was raised in the Moravian Church and theologically trained there, so that his writings often reflect concern for humanitarian causes, such as the abolition of slavery and the exploitation of child chimney sweeps.

Christopher Vane, 1st Baron Barnard, was an English peer. He served in Parliament for Durham after his brother, Thomas, died 4 days after being elected the MP for Durham. Then, again from January 1689 to November 1690 for Boroughbridge. He served in the Commons as a Whig collaborator during the passage of the Bill of Rights which his father, Sir Henry Vane the Younger, had fought for religious and civil liberty before his beheading in 1662. He is known for his disputes with his heirs and for employing Peter Smart, father of the poet Christopher Smart, as a steward.

A Christian child's prayer is Christian prayer recited primarily by children that is typically short, rhyming, or has a memorable tune. It is usually said before bedtime, to give thanks for a meal, or as a nursery rhyme. Many of these prayers are either quotes from the Bible, or set traditional texts.

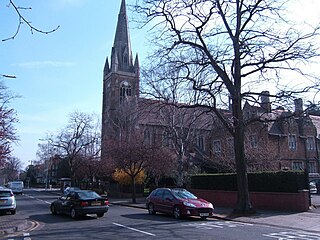

Rejoice in the Lamb is a cantata for four soloists, SATB choir and organ composed by Benjamin Britten in 1943 and uses text from the poem Jubilate Agno by Christopher Smart (1722–1771). The poem, written while Smart was in an asylum, depicts idiosyncratic praise and worship of God by different things including animals, letters of the alphabet and musical instruments. Britten was introduced to the poem by W. H. Auden whilst visiting the United States, selecting 48 lines of the poem to set to music with the assistance of Edward Sackville-West. The cantata was commissioned by the Reverend Walter Hussey for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the consecration of St Matthew's Church, Northampton. Critics praised the work for its uniqueness and creative handling of the text. Rejoice in the Lamb has been arranged for chorus, solos and orchestral accompaniment, and for SSAA choir and organ.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Jubilate Agno is a religious poem by Christopher Smart, and was written between 1759 and 1763, during Smart's confinement for insanity in St. Luke's Hospital, Bethnal Green, London. The poem was first published in 1939 under the title Rejoice in the Lamb: A Song from Bedlam, and edited by W. F. Stead from Smart's manuscript, which Stead had discovered in a private library.

Hymns and Spiritual Songs for the Fasts and Festivals of the Church of England, by Christopher Smart, was published in 1765, along with a translation of the Psalms of David and a new version of A Song to David. He wrote these poems while he was in a mental asylum and during the time he wrote Jubilate Agno.

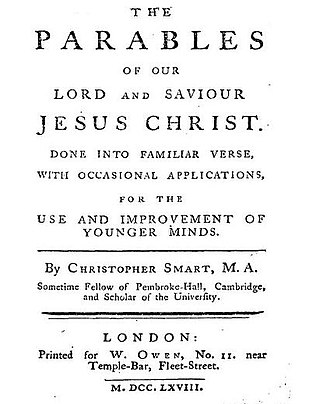

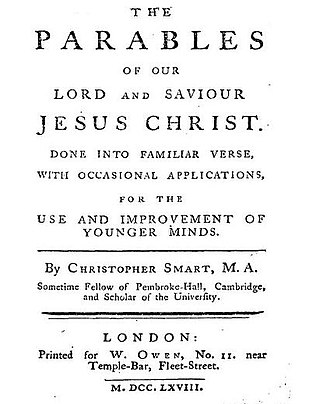

The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ Done into Familiar Verse, with Occasional Applications, for the Use and Improvement of Younger Minds was written by Christopher Smart and published in 1768. The Parables are a collection of parables from the Bible, which includes lessons from both the Old Testament and the New Testament. The book depicts the parables in verse form.

A Song to David, a 1763 poem by Christopher Smart, was, debatably, most likely written during his stay in a mental asylum while he wrote Jubilate Agno. Although it received mixed reviews, it was his most famous work until the discovery of Jubilate Agno.

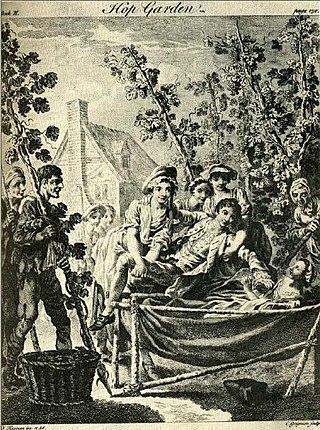

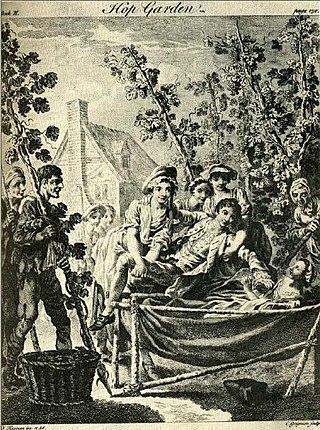

The Hop-Garden by Christopher Smart was first published in Poems on Several Occasions, 1752. The poem is rooted the Virgilian georgic and Augustan literature; it is one of the first long poems published by Smart. The poem is literally about a hop garden, and, in the Virgilian tradition, attempts to instruct the audience in how to farm hops properly.

In 1752, Henry Fielding started a "paper war", a long-term dispute with constant publication of pamphlets attacking other writers, between the various authors on London's Grub Street. Although it began as a dispute between Fielding and John Hill, other authors, such as Christopher Smart, Bonnell Thornton, William Kenrick, Arthur Murphy and Tobias Smollett, were soon dedicating their works to aid various sides of the conflict.

The Hilliad was Christopher Smart's mock epic poem written as a literary attack upon John Hill on 1 February 1753. The title is a play on Alexander Pope's The Dunciad with a substitution of Hill's name, which represents Smart's debt to Pope for the form and style of The Hilliad as well as a punning reference to the Iliad. In "Book the First" of The Hilliad, Hillario is seduced by a Sibyl to give up his career as an apothecary and instead becomes a writer. However, his fortune quickly descends with Hillario ultimately turning into the "arch-dunce".

The English poet Christopher Smart (1722–1771) was confined to mental asylums from May 1757 until January 1763. Smart was admitted to St Luke's Hospital for Lunatics, Upper Moorfields, London, on 6 May 1757. He was taken there by his father-in-law, John Newbery, although he may have been confined in a private madhouse before then. While in St Luke's he wrote Jubilate Agno and A Song to David, the poems considered to be his greatest works. Although many of his contemporaries agreed that Smart was "mad", accounts of his condition and its ramifications varied, and some felt that he had been committed unfairly.

Hannah is an oratorio in three acts by Christopher Smart with a score composed by John Worgan. It was first performed in Haymarket theater 3 April 1764. It was supposed to have a second performance, but that performance was postponed and eventually cancelled over a lack of singers. A libretto was published for its run and a libretto with full score was published later that year.

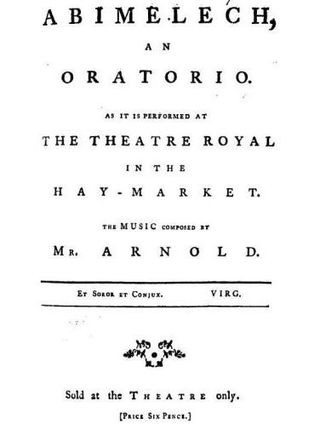

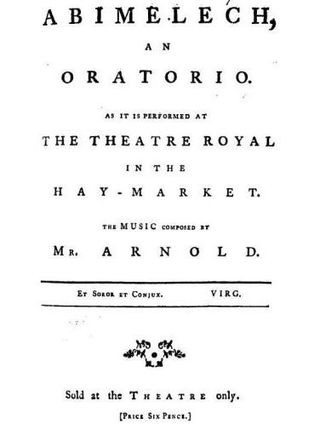

Abimelech is an oratorio in three acts written by Christopher Smart and put to music by Samuel Arnold. It was first performed in the Haymarket Theatre in 1768. A heavily revised version of the oratorio ran at Covent Garden in 1772. Abimelech was the second of two oratorio librettos written by Smart, the first being Hannah written in 1764. Just like Hannah, Abimelech ran for only one night, each time. It was to be Smart's last work dedicated to an adult audience.

Vala, or The Four Zoas is one of the uncompleted prophetic books by the English poet William Blake, begun in 1797. The eponymous main characters of the book are the Four Zoas, who were created by the fall of Albion in Blake's mythology. It consists of nine books, referred to as "nights". These outline the interactions of the Zoas, their fallen forms and their Emanations. Blake intended the book to be a summation of his mythic universe but, dissatisfied, he abandoned the effort in 1807, leaving the poem in a rough draft and its engraving unfinished. The text of the poem was first published, with only a small portion of the accompanying illustrations, in 1893, by the Irish poet W. B. Yeats and his collaborator, the English writer and poet Edwin John Ellis, in their three-volume book The Works of William Blake.

Divine Songs Attempted in Easy Language for the Use of Children is a collection of didactic, moral poetry for children by Isaac Watts, first published in 1715. Though Watts's hymns are now better known than these poems, Divine Songs was a ubiquitous children's book for nearly two hundred years, serving as a standard textbook in schools. By the mid-19th century there were more than one thousand editions.