Publius Vergilius Maro, usually called Virgil or Vergil in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: the Eclogues, the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid. A number of minor poems, collected in the Appendix Vergiliana, were attributed to him in ancient times, but modern scholars consider his authorship of these poems to be dubious.

Jethro Tull was an English agriculturist from Berkshire who helped to bring about the British Agricultural Revolution of the 18th century. He perfected a horse-drawn seed drill in 1701 that economically sowed the seeds in neat rows, and later developed a horse-drawn hoe. Tull's methods were adopted by many landowners and helped to provide the basis for modern agriculture.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1757.

Jacques Delille was a French poet who came to national prominence with his translation of Virgil’s Georgics and made an international reputation with his didactic poem on gardening. He barely survived the slaughter of the French Revolution and lived for some years outside France, including three years in England. The poems on abstract themes that he published after his return were less well received.

John Dyer was a painter and Welsh poet who became a priest in the Church of England. He was most recognised for Grongar Hill, one of six early poems featured in a 1726 miscellany. Longer works published later include the less successful genre poems, The Ruins of Rome (1740) and The Fleece (1757). His work has always been more anthologised than published in separate editions, but his talent was later recognised by William Wordsworth among others.

Christopher Smart was an English poet. He was a major contributor to two popular magazines, The Midwife and The Student, and a friend to influential cultural icons like Samuel Johnson and Henry Fielding. Smart, a high church Anglican, was widely known throughout London.

John Philips was an 18th-century English poet.

The Georgics is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example of peaceful rural poetry, it is a work characterized by tensions in both theme and purpose.

The Appendix Vergiliana is a collection of Latin poems traditionally ascribed as being the juvenilia of Virgil.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Jubilate Agno is a religious poem by Christopher Smart, and was written between 1759 and 1763, during Smart's confinement for insanity in St. Luke's Hospital, Bethnal Green, London. The poem was first published in 1939 under the title Rejoice in the Lamb: A Song from Bedlam, and edited by W. F. Stead from Smart's manuscript, which Stead had discovered in a private library.

Hymns and Spiritual Songs for the Fasts and Festivals of the Church of England, by Christopher Smart, was published in 1765, along with a translation of the Psalms of David and a new version of A Song to David. He wrote these poems while he was in a mental asylum and during the time he wrote Jubilate Agno.

Hymns for the Amusement of Children (1771) was the final work completed by English poet Christopher Smart. It was completed while Smart was imprisoned for outstanding debt at the King's Bench Prison, and the work is his final exploration of religion. Although Smart spent a large portion of his life in and out of debt, he was unable to survive his time in the prison and died soon after completing the Hymns.

A Song to David, a 1763 poem by Christopher Smart, was, debatably, most likely written during his stay in a mental asylum while he wrote Jubilate Agno. Although it received mixed reviews, it was his most famous work until the discovery of Jubilate Agno.

In 1752, Henry Fielding started a "paper war", a long-term dispute with constant publication of pamphlets attacking other writers, between the various authors on London's Grub Street. Although it began as a dispute between Fielding and John Hill, other authors, such as Christopher Smart, Bonnell Thornton, William Kenrick, Arthur Murphy and Tobias Smollett, were soon dedicating their works to aid various sides of the conflict.

The Hilliad was Christopher Smart's mock epic poem written as a literary attack upon John Hill on 1 February 1753. The title is a play on Alexander Pope's The Dunciad with a substitution of Hill's name, which represents Smart's debt to Pope for the form and style of The Hilliad as well as a punning reference to the Iliad. In "Book the First" of The Hilliad, Hillario is seduced by a Sibyl to give up his career as an apothecary and instead becomes a writer. However, his fortune quickly descends with Hillario ultimately turning into the "arch-dunce".

The English poet Christopher Smart (1722–1771) was confined to mental asylums from May 1757 until January 1763. Smart was admitted to St Luke's Hospital for Lunatics, Upper Moorfields, London, on 6 May 1757. He was taken there by his father-in-law, John Newbery, although he may have been confined in a private madhouse before then. While in St Luke's he wrote Jubilate Agno and A Song to David, the poems considered to be his greatest works. Although many of his contemporaries agreed that Smart was "mad", accounts of his condition and its ramifications varied, and some felt that he had been committed unfairly.

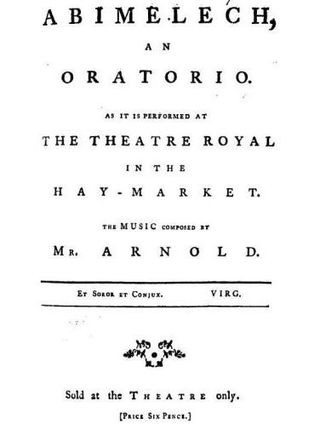

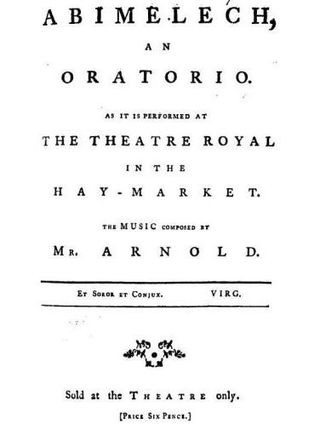

Abimelech is an oratorio in three acts written by Christopher Smart and put to music by Samuel Arnold. It was first performed in the Haymarket Theatre in 1768. A heavily revised version of the oratorio ran at Covent Garden in 1772. Abimelech was the second of two oratorio librettos written by Smart, the first being Hannah written in 1764. Just like Hannah, Abimelech ran for only one night, each time. It was to be Smart's last work dedicated to an adult audience.

Cento Vergilianus de laudibus Christi is a Latin poem arranged by Faltonia Betitia Proba after her conversion to Christianity. A cento is a poetic work composed of verses or passages taken from other authors and re-arranged in a new order. This poem reworks verses extracted from the work of Virgil to tell stories from the Old and New Testament of the Christian Bible. Much of the work focuses on the story of Jesus Christ.

The Sugar Cane was a pioneering georgic poem adapted to a West Indian theme, first published in 1764. With renewed interest in Caribbean literature, and especially after a new edition was published in 2000, it has attracted critical attention, especially its author's attitude towards slavery.