Related Research Articles

Spaced repetition is an evidence-based learning technique that is usually performed with flashcards. Newly introduced and more difficult flashcards are shown more frequently, while older and less difficult flashcards are shown less frequently in order to exploit the psychological spacing effect. The use of spaced repetition has been proven to increase the rate of learning.

A second language (L2) is a language spoken in addition to one's first language (L1). A second language may be a neighbouring language, another language of the speaker's home country, or a foreign language. A speaker's dominant language, which is the language a speaker uses most or is most comfortable with, is not necessarily the speaker's first language. For example, the Canadian census defines first language for its purposes as "the first language learned in childhood and still spoken", recognizing that for some, the earliest language may be lost, a process known as language attrition. This can happen when young children start school or move to a new language environment.

Recall in memory refers to the mental process of retrieval of information from the past. Along with encoding and storage, it is one of the three core processes of memory. There are three main types of recall: free recall, cued recall and serial recall. Psychologists test these forms of recall as a way to study the memory processes of humans and animals. Two main theories of the process of recall are the two-stage theory and the theory of encoding specificity.

Source amnesia is the inability to remember where, when or how previously learned information has been acquired, while retaining the factual knowledge. This branch of amnesia is associated with the malfunctioning of one's explicit memory. It is likely that the disconnect between having the knowledge and remembering the context in which the knowledge was acquired is due to a dissociation between semantic and episodic memory – an individual retains the semantic knowledge, but lacks the episodic knowledge to indicate the context in which the knowledge was gained.

Hindsight bias, also known as the knew-it-all-along phenomenon or creeping determinism, is the common tendency for people to perceive past events as having been more predictable than they were.

Dyscalculia is a learning disability resulting in difficulty learning or comprehending arithmetic, such as difficulty in understanding numbers, numeracy, learning how to manipulate numbers, performing mathematical calculations, and learning facts in mathematics. It is sometimes colloquially referred to as "math dyslexia", though this analogy can be misleading as they are distinct syndromes.

Multiple choice (MC), objective response or MCQ(for multiple choice question) is a form of an objective assessment in which respondents are asked to select only the correct answer from the choices offered as a list. The multiple choice format is most frequently used in educational testing, in market research, and in elections, when a person chooses between multiple candidates, parties, or policies.

The testing effect suggests long-term memory is increased when part of the learning period is devoted to retrieving information from memory. It is different from the more general practice effect, defined in the APA Dictionary of Psychology as "any change or improvement that results from practice or repetition of task items or activities."

Metacognition is an awareness of one's thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The term comes from the root word meta, meaning "beyond", or "on top of". Metacognition can take many forms, such as reflecting on one's ways of thinking, and knowing when and how oneself and others use particular strategies for problem-solving. There are generally two components of metacognition: (1) cognitive conceptions and (2) cognitive regulation system. Research has shown that both components of metacognition play key roles in metaconceptual knowledge and learning. Metamemory, defined as knowing about memory and mnemonic strategies, is an important aspect of metacognition.

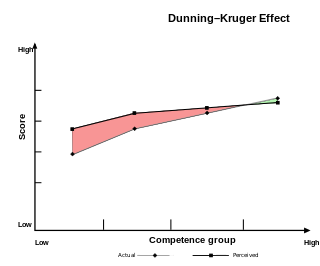

The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people with limited competence in a particular domain overestimate their abilities. It was first described by David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999. Some researchers also include the opposite effect for high performers: their tendency to underestimate their skills. In popular culture, the Dunning–Kruger effect is often misunderstood as a claim about general overconfidence of people with low intelligence instead of specific overconfidence of people unskilled at a particular task.

Choice-supportive bias or post-purchase rationalization is the tendency to retroactively ascribe positive attributes to an option one has selected and/or to demote the forgone options. It is part of cognitive science, and is a distinct cognitive bias that occurs once a decision is made. For example, if a person chooses option A instead of option B, they are likely to ignore or downplay the faults of option A while amplifying or ascribing new negative faults to option B. Conversely, they are also likely to notice and amplify the advantages of option A and not notice or de-emphasize those of option B.

The overconfidence effect is a well-established bias in which a person's subjective confidence in their judgments is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of those judgments, especially when confidence is relatively high. Overconfidence is one example of a miscalibration of subjective probabilities. Throughout the research literature, overconfidence has been defined in three distinct ways: (1) overestimation of one's actual performance; (2) overplacement of one's performance relative to others; and (3) overprecision in expressing unwarranted certainty in the accuracy of one's beliefs.

Tip of the tongue is the phenomenon of failing to retrieve a word or term from memory, combined with partial recall and the feeling that retrieval is imminent. The phenomenon's name comes from the saying, "It's on the tip of my tongue." The tip of the tongue phenomenon reveals that lexical access occurs in stages.

Learning disability, learning disorder, or learning difficulty is a condition in the brain that causes difficulties comprehending or processing information and can be caused by several different factors. Given the "difficulty learning in a typical manner", this does not exclude the ability to learn in a different manner. Therefore, some people can be more accurately described as having a "learning difference", thus avoiding any misconception of being disabled with a possible lack of an ability to learn and possible negative stereotyping. In the United Kingdom, the term "learning disability" generally refers to an intellectual disability, while conditions such as dyslexia and dyspraxia are usually referred to as "learning difficulties".

Metamemory or Socratic awareness, a type of metacognition, is both the introspective knowledge of one's own memory capabilities and the processes involved in memory self-monitoring. This self-awareness of memory has important implications for how people learn and use memories. When studying, for example, students make judgments of whether they have successfully learned the assigned material and use these decisions, known as "judgments of learning", to allocate study time.

Corrective feedback is a frequent practice in the field of learning and achievement. It typically involves a learner receiving either formal or informal feedback on their understanding or performance on various tasks by an agent such as teacher, employer or peer(s). To successfully deliver corrective feedback, it needs to be nonevaluative, supportive, timely, and specific.

In psychology, the misattribution of memory or source misattribution is the misidentification of the origin of a memory by the person making the memory recall. Misattribution is likely to occur when individuals are unable to monitor and control the influence of their attitudes, toward their judgments, at the time of retrieval. Misattribution is divided into three components: cryptomnesia, false memories, and source confusion. It was originally noted as one of Daniel Schacter's seven sins of memory.

The hard–easy effect is a cognitive bias that manifests itself as a tendency to overestimate the probability of one's success at a task perceived as hard, and to underestimate the likelihood of one's success at a task perceived as easy. The hard-easy effect takes place, for example, when individuals exhibit a degree of underconfidence in answering relatively easy questions and a degree of overconfidence in answering relatively difficult questions. "Hard tasks tend to produce overconfidence but worse-than-average perceptions," reported Katherine A. Burson, Richard P. Larrick, and Jack B. Soll in a 2005 study, "whereas easy tasks tend to produce underconfidence and better-than-average effects."

The illusory truth effect is the tendency to believe false information to be correct after repeated exposure. This phenomenon was first identified in a 1977 study at Villanova University and Temple University. When truth is assessed, people rely on whether the information is in line with their understanding or if it feels familiar. The first condition is logical, as people compare new information with what they already know to be true. Repetition makes statements easier to process relative to new, unrepeated statements, leading people to believe that the repeated conclusion is more truthful. The illusory truth effect has also been linked to hindsight bias, in which the recollection of confidence is skewed after the truth has been received.

Active student response (ASR) techniques are strategies to elicit observable responses from students in a classroom. They are grounded in the field of behavioralism and operate by increasing opportunities reinforcement during class time, typically in the form of instructor praise. Active student response techniques are designed so that student behavior, such as responding aloud to a question, is quickly followed by reinforcement if correct. Common form of active student response techniques are choral responding, response cards, guided notes, and clickers. While they are commonly used for disabled populations, these strategies can be applied at many different levels of education. Implementing active student response techniques has been shown to increase learning, but may require extra supplies or preparation by the instructor.

References

- ↑ Metcalfe, J. "Older Beats Younger When It Comes to Correcting Mistakes". Psychological Science. Association for Psychological Science. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ Metcalfe, Janet; Finn, Bridgid (March 2011). "People's Hypercorrection of High Confidence Errors: Did They Know it All Along?". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 37 (2): 437–448. doi:10.1037/a0021962. ISSN 0278-7393. PMC 3079415 . PMID 21355668.

- 1 2 Metcalfe, Janet (2017). "Learning from Errors". Annual Review of Psychology. 68: 465–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022 . PMID 27648988.

- ↑ Butterfield, B.; Metcalfe, J. (2001). "Errors committed with high confidence are hypercorrected". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 27 (6): 1491–1494. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.27.6.1491. PMID 11713883.

- ↑ Kulhavy, Raymond W. (1977). "Feedback in Written Instruction". Review of Educational Research. 47 (2): 211–232. doi:10.3102/00346543047002211. JSTOR 1170128.

- ↑ Butterfield, Brady; Metcalfe, Janet (2006). "The correction of errors committed with high confidence". Metacognition and Learning. 1: 69–84. doi:10.1007/s11409-006-6894-z. S2CID 11430724.

- 1 2 3 4 Butler, Andrew C.; Fazio, Lisa K.; Marsh, Elizabeth J. (2011-12-01). "The hypercorrection effect persists over a week, but high-confidence errors return". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 18 (6): 1238–1244. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0173-y . ISSN 1531-5320. PMID 21989771.

- 1 2 Metcalfe, Janet; Miele, David B. (2014). "Hypercorrection of high confidence errors: Prior testing both enhances delayed performance and blocks the return of the errors". Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 3 (3): 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.04.001.

- ↑ Metcalfe, Janet; Butterfield, Brady; Habeck, Christian; Stern, Yaakov (2012). "Neural Correlates of People's Hypercorrection of Their False Beliefs". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 24 (7): 1571–1583. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00228. PMC 3970786 . PMID 22452558.

- ↑ Carpenter, Shana K.; Haynes, Cynthia L.; Corral, Daniel; Yeung, Kam Leung (2018). "Hypercorrection of high-confidence errors in the classroom". Memory. 26 (10): 1379–1384. doi:10.1080/09658211.2018.1477164. PMID 29781391. S2CID 29160922.

- ↑ Metcalfe, Janet (2017-01-03). "Learning from Errors". Annual Review of Psychology. 68 (1): 465–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022 . ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 27648988.

- 1 2 Eich, Teal S.; Stern, Yaakov; Metcalfe, Janet (2013). "The hypercorrection effect in younger and older adults". Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 20 (5): 511–521. doi:10.1080/13825585.2012.754399. PMC 3604148 . PMID 23241028.

- ↑ Metcalfe, J.; Casal-Roscum, L.; Radin, A.; Friedman, D. (2015). "On Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks". Psychological Science. 26 (12): 1833–1842. doi:10.1177/0956797615597912. PMC 4679660 . PMID 26494598.

- 1 2 Metcalfe, Janet; Casal-Roscum, Lindsey; Radin, Arielle; Friedman, David (December 2015). "On Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks". Psychological Science. 26 (12): 1833–1842. doi:10.1177/0956797615597912. ISSN 0956-7976. PMC 4679660 . PMID 26494598.

- 1 2 Williams, David M; Bergström, Zara; Grainger, Catherine (2016-12-15). "Metacognitive monitoring and the hypercorrection effect in autism and the general population: Relation to autism(-like) traits and mindreading" (PDF). Autism. 22 (3): 259–270. doi:10.1177/1362361316680178. hdl: 1893/24780 . ISSN 1362-3613. PMID 29671645. S2CID 4951642.