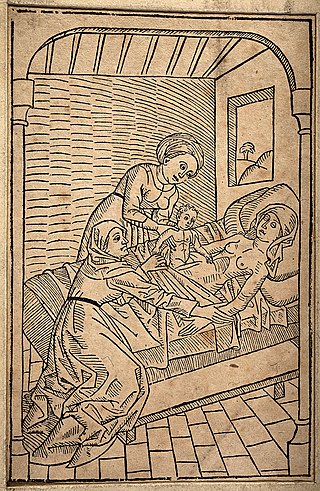

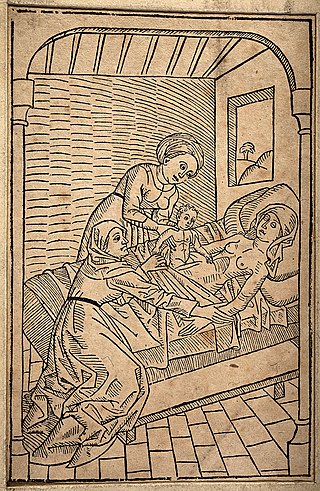

Caesarean section, also known as C-section, cesarean, or caesarean delivery, is the surgical procedure by which one or more babies are delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen. It is often performed because vaginal delivery would put the mother or child at risk. Reasons for the operation include obstructed labor, twin pregnancy, high blood pressure in the mother, breech birth, shoulder presentation, and problems with the placenta or umbilical cord. A caesarean delivery may be performed based upon the shape of the mother's pelvis or history of a previous C-section. A trial of vaginal birth after C-section may be possible. The World Health Organization recommends that caesarean section be performed only when medically necessary.

The paternal rights and abortion issue is an extension of both the abortion debate and the fathers' rights movement. Abortion can be a factor for disagreement and lawsuit between partners.

Many jurisdictions have laws applying to minors and abortion. These parental involvement laws require that one or more parents consent or be informed before their minor daughter may legally have an abortion.

In case of a previous caesarean section a subsequent pregnancy can be planned beforehand to be delivered by either of the following two main methods:

Abortion is illegal in El Salvador. The law formerly permitted an abortion to be performed under some limited circumstances, but in 1998 all exceptions were removed when a new abortion law went into effect.

Pregnant patients' rights regarding medical care during the pregnancy and childbirth are specifically a patient's rights within a medical setting and should not be confused with pregnancy discrimination. A great deal of discussion regarding pregnant patients' rights has taken place in the United States.

This is a timeline of reproductive rights legislation, a chronological list of laws and legal decisions affecting human reproductive rights. Reproductive rights are a sub-set of human rights pertaining to issues of reproduction and reproductive health. These rights may include some or all of the following: the right to legal or safe abortion, the right to birth control, the right to access quality reproductive healthcare, and the right to education and access in order to make reproductive choices free from coercion, discrimination, and violence. Reproductive rights may also include the right to receive education about contraception and sexually transmitted infections, and freedom from coerced sterilization, abortion, and contraception, and protection from practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM).

Pemberton v. Tallahassee Memorial Regional Center, 66 F. Supp. 2d 1247, is a case in the United States regarding reproductive rights. In particular, the case explored the limits of a woman's right to choose her medical treatment in light of fetal rights at the end of pregnancy.

Abortion in Paraguay is illegal except in case of the threat to the life of the woman. Anyone who performs an abortion can be sentenced to 15 to 30 months in prison. If the abortion is done without the consent of the woman, the punishment is increased to 2 to 5 years. If the death of the woman occurred as a result of the abortion, the person who did the procedure can be sentenced to 4 to 6 years in prison, and 5 to 10 years in cases in which she did not consent. In Paraguay, 23 out of 100 deaths of young women are the result of illegal abortions. Concerning this death rate, Paraguay has one of the highest in the region.

People v. Pointer, 151 Cal.App.3d 1128, 199 Cal. Rptr. 357 (1984), is a criminal law case from the California Court of Appeal, First District, is significant because the trial judge included in his sentencing a prohibition on the defendant becoming pregnant during her period of probation. The appellate court held that such a prohibition was outside the bounds of a judge's sentencing authority. The case was remanded for resentencing to undo the overly broad prohibition against conception.

Burton v. Florida, 49 So.3d 263 (2010), was a Florida District Court of Appeals case ruling that the court cannot impose unwanted treatment on a pregnant woman "in the best interests of the fetus" without providing evidence of fetal viability.

Foeticide, or feticide, is the act of killing a fetus, or causing a miscarriage. Definitions differ between legal and medical applications, whereas in law, feticide frequently refers to a criminal offense, in medicine the term generally refers to a part of an abortion procedure in which a provider intentionally induces fetal demise to avoid the chance of an unintended live birth, or as a standalone procedure in the case of selective reduction.

The North Carolina Woman's Right to Know Act is a passed North Carolina statute which is referred to as an "informed consent" law. The bill requires practitioners read a state-mandated informational materials, often referred to as counseling scripts, to patients at least 72 hours before the abortion procedure. The patient and physician must certify that the information on informed consent has been provided before the procedure. The law also mandated the creation of a state-maintained website and printed informational materials, containing information about: public and private services available during pregnancy, anatomical and physiological characteristics of gestational development, and possible adverse effects of abortion and pregnancy. A review of twenty-three U.S. states informed consent materials found that North Carolina had the "highest level of inaccuracies," with 36 out of 78 statements rated as inaccurate, or 46%.

Madrigal v. Quilligan was a federal class action lawsuit from Los Angeles County, California, involving sterilization of Latina women that occurred either without informed consent, or through coercion. Although the judge ruled in favor of the doctors, the case led to better informed consent for patients, especially those who are not native English speakers.

V.C. vs Slovakia was the first case in which the European Court for Human Rights ruled in favor of a Romani woman who was a victim of forced sterilization in the state hospital in Slovakia. It is one of many cases of forced sterilization of Roma women brought to the Court by the Slovak feminist group Center for Civil and Human Rights from Košice.

Sterilization law is the area of law, that concerns a person's purported right to choose or refuse reproductive sterilization and when a given government may limit it. In the United States, it is typically understood to touch on federal and state constitutional law, statutory law, administrative law, and common law. This article primarily focuses on laws concerning compulsory sterilization that have not been repealed or abrogated, i.e. are still good laws, in whole or in part, in each jurisdiction.

A resuscitative hysterotomy, also referred to as a perimortem Caesarean section (PMCS) or perimortem Caesarean delivery (PMCD), is a hysterotomy performed to resuscitate a woman in middle to late pregnancy who has entered cardiac arrest. Combined with a laparotomy, the procedure results in a Caesarean section that removes the fetus, thereby abolishing the aortocaval compression caused by the pregnant uterus. This improves the mother's chances of return of spontaneous circulation, and may potentially also deliver a viable neonate. The procedure may be performed by obstetricians, emergency physicians or surgeons depending on the situation.

Maternal-fetal conflict, also known as obstetric conflict, occurs when a pregnant woman’s (maternal) interests conflict with the interests of the fetus. Legal and ethical considerations involving women's rights and the rights of the fetus as a patient and future child, have become more complicated with advances in medicine and technology. Maternal-fetal conflict can occur in situations where the mother denies health recommendations that can benefit the fetus or make life choices that can harm the fetus. There are maternal-fetal conflict situations where the law becomes involved, but most physicians avoid involving the law for various reasons.

As of 2024, abortion is illegal in Indiana. It is only legal in cases involving fatal fetal abnormalities, to preserve the life and physical health of the mother, and in cases of rape or incest up to 10 weeks of pregnancy. Previously abortion in Indiana was legal up to 20 weeks; a near-total ban that was scheduled to take effect on August 1, 2023, was placed on hold due to further legal challenges, but is set to take place, after the Indiana Supreme Court denied an appeal by the ACLU, and once it certifies a previous ruling that an abortion ban doesn't violate the state constitution. In the wake of the 2022 Dobbs Supreme Court ruling, abortion in Indiana remained legal despite Indiana lawmakers voting in favor of a near-total abortion ban on August 5, 2022. Governor Eric Holcomb signed this bill into law the same day. The new law became effective on September 15, 2022. However, on September 22, 2022, Special Judge Kelsey B. Hanlon of the Monroe County Circuit Court granted a preliminary injunction against the enforcement of the ban. Her ruling allows the state's previous abortion law, which allows abortions up to 20 weeks after fertilization with exceptions for rape and incest, to remain in effect.

Planned Parenthood v. Rounds, 686 F.3d 889, is an Eighth Circuit decision addressing the constitutionality of a South Dakota law which forced doctors to make certain disclosures to patients seeking abortions. The challenged statute required physicians to convey to their abortion-seeking patients a number of state-mandated disclosures, including a statement that abortions caused an "[i]ncreased risk of suicide ideation and suicide." Planned Parenthood of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, along with its medical director Dr. Carol E. Ball, challenged the South Dakota law, arguing that it violated patients' and physicians' First Amendment free speech rights and Fourteenth Amendment due process rights. After several appeals and remands, the Eighth Circuit, sitting en banc, upheld the South Dakota law, holding that the mandated suicide advisement was not "unconstitutionally misleading or irrelevant," and did "not impose an unconstitutional burden on women seeking abortions or their physicians." This supplemented the Eighth Circuit's earlier rulings in this case, where the court determined that the state was allowed to impose a restrictive emergency exception on abortion procedures and to force physicians to convey disclosures regarding the woman's relationship to the fetus and the humanity of the fetus.