Perfume is a mixture of fragrant essential oils or aroma compounds (fragrances), fixatives and solvents, usually in liquid form, used to give the human body, animals, food, objects, and living-spaces an agreeable scent. Perfumes can be defined as substances that emit and diffuse a pleasant and fragrant odor. They consist of manmade mixtures of aromatic chemicals and essential oils. The 1939 Nobel Laureate for Chemistry, Leopold Ružička stated in 1945 that "right from the earliest days of scientific chemistry up to the present time, perfumes have substantially contributed to the development of organic chemistry as regards methods, systematic classification, and theory."

Incense is an aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremonial reasons. It may also be used as a simple deodorant or insect repellent.

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus Santalum. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods. Sandalwood is often cited as one of the most expensive woods in the world. Both the wood and the oil produce a distinctive fragrance that has been highly valued for centuries. Consequently, some species of these slow-growing trees have suffered over-harvesting in the past.

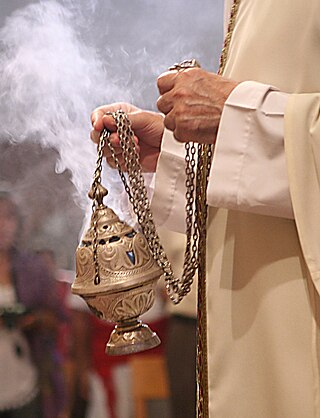

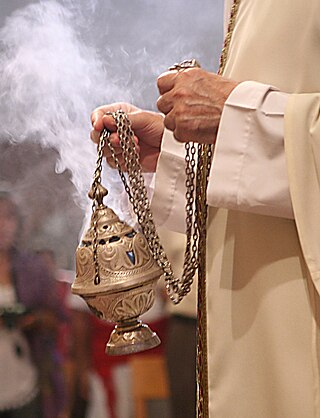

A censer, incense burner, perfume burner or pastille burner is a vessel made for burning incense or perfume in some solid form. They vary greatly in size, form, and material of construction, and have been in use since ancient times throughout the world. They may consist of simple earthenware bowls or fire pots to intricately carved silver or gold vessels, small table top objects a few centimetres tall to as many as several metres high. Many designs use openwork to allow a flow of air. In many cultures, burning incense has spiritual and religious connotations, and this influences the design and decoration of the censer.

Ikebana is the Japanese art of flower arrangement. It is also known as kadō. The origin of ikebana can be traced back to the ancient Japanese custom of erecting evergreen trees and decorating them with flowers as yorishiro to invite the gods.

Agarwood, aloeswood, eaglewood, gharuwood or the Wood of Gods, most commonly referred to as oud or oudh, is a fragrant, dark and resinous wood used in incense, perfume, and small hand carvings. It forms in the heartwood of Aquilaria trees after they become infected with a type of Phaeoacremonium mold, P. parasitica. The tree defensively secretes a resin to combat the fungal infestation. Prior to becoming infected, the heartwood mostly lacks scent, and is relatively light and pale in colouration. However, as the infection advances and the tree produces its fragrant resin as a final option of defense, the heartwood becomes very dense, dark, and saturated with resin. This product is harvested, and most famously referred to in cosmetics under the scent names of oud, oodh or aguru; however, it is also called aloes, agar, as well as gaharu or jinko. With thousands of years of known use, and valued across Muslim, Christian, and Hindu communities, oud is prized in Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures for its distinctive fragrance, utilized in colognes, incense and perfumes.

Nag champa is a natural fragrance of Indian origin. It is made from a combination of sandalwood and either champak or frangipani. When frangipani is used, the fragrance is usually referred to simply as champa.

Kōdō is the art of appreciating Japanese incense, and involves using incense within a structure of codified conduct. Kōdō includes all aspects of the incense process, from the tools, to activities such as the incense-comparing games kumikō (組香) and genjikō (源氏香). Kōdō is counted as one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement, along with ikebana for flower arrangement, and chadō for tea and the tea ceremony.

The incense clock is a timekeeping device that originated from China during the Song Dynasty (960–1279) and spread to neighboring East Asian countries such as Japan and Korea. The clocks' bodies are effectively specialized censers that hold incense sticks or powdered incense that have been manufactured and calibrated to a known rate of combustion, used to measure minutes, hours, or days. The clock may also contain bells and gongs which act as strikers. Although the water clock and astronomical clock were known in China, incense clocks were commonly used at homes and temples in dynastic times.

Fragrance extraction refers to the separation process of aromatic compounds from raw materials, using methods such as distillation, solvent extraction, expression, sieving, or enfleurage. The results of the extracts are either essential oils, absolutes, concretes, or butters, depending on the amount of waxes in the extracted product.

Baieidō is a Japanese incense company established in 1657, located in Sakai, Osaka Prefecture, It is one of the oldest traditional incense makers in Japan.

Nippon Kodo is a Japanese incense company that traces their origins back over 400 years to an incense maker known as Koju, who made incense for the Emperor of Japan. The Nippon Kodo Group was established in August 1965, has acquired several other incense companies worldwide, and has offices in New York City, Los Angeles, Paris, Chicago, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Tokyo. Mainichi-Koh, introduced in 1912, is the company's most popular product.

India is the world's main incense producing country, and is also a major exporter to other countries. In India, incense sticks are called Agarbatti (Agar: from Dravidian probably Tamil அகில், அகிர், Sanskrit varti, meaning "stick". An older term "Dhūpavarti" is more commonly used in ancient and medieval texts which encompasses various types of stick incense recipes. Incense is part of the cottage industry in India and important part of many religions in the region since ancient times. The method of incense making with a bamboo stick as a core originated in India at the end of the 19th century, largely replacing the rolled, extruded or shaped method which is still used in India for dhoop.

The word perfume is used today to describe scented mixtures and is derived from the Latin word per fumus. The word perfumery refers to the art of making perfumes. Perfume was produced by ancient Greeks, and perfume was also refined by the Romans, the Persians and the Arabs. Although perfume and perfumery also existed in East Asia, much of its fragrances were incense based. The basic ingredients and methods of making perfumes are described by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia.

Lorenzo Villoresi is a perfumer in Florence, Italy. His study and travel in the Middle East has greatly influenced his work and some of his most important fragrances are Orientals, exotic perfumes of spices, amber, incense, resins, vanilla, sandalwoods and other aromatics. He continues in the long tradition of perfumery in Florence, arguably where modern perfume making began. The LV house opened in 1990 in the 15th-century family palace, overlooking the Arno.

Religious use of incense has its origins in antiquity. The burned incense may be intended as a symbolic or sacrificial offering to various deities or spirits, or to serve as an aid in prayer.

Stacte and nataph are names used for one component of the Solomon's Temple incense, the Ketoret, specified in the Book of Exodus. Variously translated to the Greek term or to an unspecified "gum resin" or similar, it was to be mixed in equal parts with onycha, galbanum and mixed with pure frankincense and they were to "beat some of it very small" for burning on the altar of the tabernacle.

Incense in China is traditionally used in a wide range of Chinese cultural activities including religious ceremonies, ancestor veneration, traditional medicine, and in daily life. Known as xiang, incense was used by the Chinese cultures starting from Neolithic times with it coming to greater prominence starting from the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties.

The incense offering, a blend of aromatic substances that exhale perfume during combustion, usually consisting of spices and gums burnt as an act of worship, occupied a prominent position in the sacrificial legislation of the ancient Hebrews.