General anaesthetics are often defined as compounds that induce a loss of consciousness in humans or loss of righting reflex in animals. Clinical definitions are also extended to include an induced coma that causes lack of awareness to painful stimuli, sufficient to facilitate surgical applications in clinical and veterinary practice. General anaesthetics do not act as analgesics and should also not be confused with sedatives. General anaesthetics are a structurally diverse group of compounds whose mechanisms encompass multiple biological targets involved in the control of neuronal pathways. The precise workings are the subject of some debate and ongoing research.

Anesthesia or anaesthesia is a state of controlled, temporary loss of sensation or awareness that is induced for medical or veterinary purposes. It may include some or all of analgesia, paralysis, amnesia, and unconsciousness. An individual under the effects of anesthetic drugs is referred to as being anesthetized.

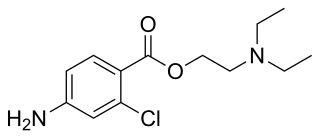

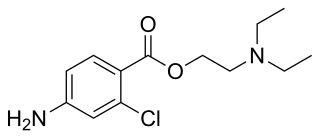

A local anesthetic (LA) is a medication that causes absence of all sensation in a specific body part without loss of consciousness, providing local anesthesia, as opposed to a general anesthetic, which eliminates all sensation in the entire body and causes unconsciousness. Local anesthetics are most commonly used to eliminate pain during or after surgery. When it is used on specific nerve pathways, paralysis also can be induced.

General anaesthesia (UK) or general anesthesia (US) is a method of medically inducing loss of consciousness that renders a patient unarousable even with painful stimuli. This effect is achieved by administering either intravenous or inhalational general anaesthetic medications, which often act in combination with an analgesic and neuromuscular blocking agent. Spontaneous ventilation is often inadequate during the procedure and intervention is often necessary to protect the airway. General anaesthesia is generally performed in an operating theater to allow surgical procedures that would otherwise be intolerably painful for a patient, or in an intensive care unit or emergency department to facilitate endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients. Depending on the procedure, general anaesthesia may be optional or required. Regardless of whether a patient may prefer to be unconscious or not, certain pain stimuli could result in involuntary responses from the patient that may make an operation extremely difficult. Thus, for many procedures, general anaesthesia is required from a practical perspective.

Spinal anaesthesia, also called spinal block, subarachnoid block, intradural block and intrathecal block, is a form of neuraxial regional anaesthesia involving the injection of a local anaesthetic or opioid into the subarachnoid space, generally through a fine needle, usually 9 cm (3.5 in) long. It is a safe and effective form of anesthesia usually performed by anesthesiologists that can be used as an alternative to general anesthesia commonly in surgeries involving the lower extremities and surgeries below the umbilicus. The local anesthetic with or without an opioid injected into the cerebrospinal fluid provides locoregional anaesthesia: true anaesthesia, motor, sensory and autonomic (sympathetic) blockade. Administering analgesics in the cerebrospinal fluid without a local anaesthetic produces locoregional analgesia: markedly reduced pain sensation, some autonomic blockade, but no sensory or motor block. Locoregional analgesia, due to mainly the absence of motor and sympathetic block may be preferred over locoregional anaesthesia in some postoperative care settings. The tip of the spinal needle has a point or small bevel. Recently, pencil point needles have been made available.

An anesthetic or anaesthetic is a drug used to induce anesthesia — in other words, to result in a temporary loss of sensation or awareness. They may be divided into two broad classes: general anesthetics, which result in a reversible loss of consciousness, and local anesthetics, which cause a reversible loss of sensation for a limited region of the body without necessarily affecting consciousness.

Epidural administration is a method of medication administration in which a medicine is injected into the epidural space around the spinal cord. The epidural route is used by physicians and nurse anesthetists to administer local anesthetic agents, analgesics, diagnostic medicines such as radiocontrast agents, and other medicines such as glucocorticoids. Epidural administration involves the placement of a catheter into the epidural space, which may remain in place for the duration of the treatment. The technique of intentional epidural administration of medication was first described in 1921 by Spanish military surgeon Fidel Pagés.

Bupivacaine, marketed under the brand name Marcaine among others, is a medication used to decrease sensation in a specific small area. In nerve blocks, it is injected around a nerve that supplies the area, or into the spinal canal's epidural space. It is available mixed with a small amount of epinephrine to increase the duration of its action. It typically begins working within 15 minutes and lasts for 2 to 8 hours.

Ropivacaine (rINN) is a local anaesthetic drug belonging to the amino amide group. The name ropivacaine refers to both the racemate and the marketed S-enantiomer. Ropivacaine hydrochloride is commonly marketed by AstraZeneca under the brand name Naropin.

Nerve block or regional nerve blockade is any deliberate interruption of signals traveling along a nerve, often for the purpose of pain relief. Local anesthetic nerve block is a short-term block, usually lasting hours or days, involving the injection of an anesthetic, a corticosteroid, and other agents onto or near a nerve. Neurolytic block, the deliberate temporary degeneration of nerve fibers through the application of chemicals, heat, or freezing, produces a block that may persist for weeks, months, or indefinitely. Neurectomy, the cutting through or removal of a nerve or a section of a nerve, usually produces a permanent block. Because neurectomy of a sensory nerve is often followed, months later, by the emergence of new, more intense pain, sensory nerve neurectomy is rarely performed.

Chloroprocaine is a local anesthetic given by injection during surgical procedures and labor and delivery. Chloroprocaine vasodilates; this is in contrast to cocaine which vasoconstricts. Chloroprocaine is an ester anesthetic.

Levobupivacaine (rINN) is a local anaesthetic drug indicated for minor and major surgical anaesthesia and pain management. It is a long-acting amide-type local anaesthetic that blocks nerve impulses by inhibiting sodium ion influx into the nerve cells. Levobupivacaine is the S-enantiomer of racemic bupivacaine and therefore similar in pharmacological effects. The drug typically starts taking effect within 15 minutes and can last up to 16 hours depending on factors such as site of administration and dosage.

Esmarch bandage in its modern form is a narrow soft rubber bandage that is used to expel venous blood from a limb (exsanguinate) that has had its arterial supply cut off by a tourniquet. The limb is often elevated as the elastic pressure is applied. The exsanguination is necessary to enable some types of delicate reconstructive surgery where bleeding would obscure the working area. A bloodless area is also required to introduce local anaesthetic agents for a regional nerve block. This method was first described by Augustus Bier in 1908.

A tourniquet is a device that is used to apply pressure to a limb or extremity in order to create ischemia or stopping the flow of blood. It may be used in emergencies, in surgery, or in post-operative rehabilitation.

Veterinary anesthesia is a specialization in the veterinary medicine field dedicated to the proper administration of anesthetic agents to non-human animals to control their consciousness during procedures. A veterinarian or a Registered Veterinary Technician administers these drugs to minimize stress, destructive behavior, and the threat of injury to both the patient and the doctor. The duration of the anesthesia process goes from the time before an animal leaves for the visit to the time after the animal reaches home after the visit, meaning it includes care from both the owner and the veterinary staff. Generally, anesthesia is used for a wider range of circumstances in animals than in people not only due to their inability to cooperate with certain diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, but also due to their species, breed, size, and corresponding anatomy. Veterinary anesthesia includes anesthesia of the major species: dogs, cats, horses, cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs, as well as all other animals requiring veterinary care such as birds, pocket pets, and wildlife.

Dental anesthesia is the application of anesthesia to dentistry. It includes local anesthetics, sedation, and general anesthesia.

Brachial plexus block is a regional anesthesia technique that is sometimes employed as an alternative or as an adjunct to general anesthesia for surgery of the upper extremity. This technique involves the injection of local anesthetic agents in close proximity to the brachial plexus, temporarily blocking the sensation and ability to move the upper extremity. The subject can remain awake during the ensuing surgical procedure, or they can be sedated or even fully anesthetized if necessary.

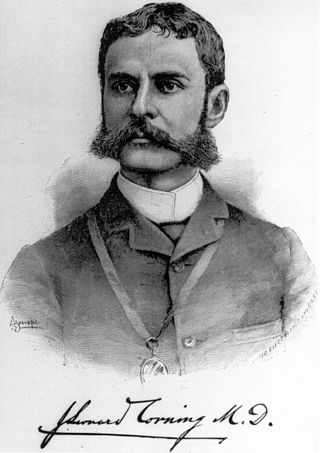

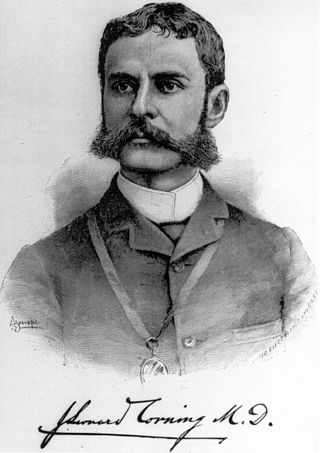

The history of neuraxial anaesthesia dates back to the late 1800s and is closely intertwined with the development of anaesthesia in general. Neuraxial anaesthesia, in particular, is a form of regional analgesia placed in or around the Central Nervous System, used for pain management and anaesthesia for certain surgeries and procedures.

Coinduction in anesthesia is a pharmacological tool whereby a combination of sedative drugs may be used to greater effect than a single agent, achieving a smoother onset of general anesthesia. The use of coinduction allows lower doses of the same anesthetic agents to be used which provides enhanced safety, faster recovery, fewer side-effects, and more predictable pharmacodynamics. Coinduction is used in human medicine and veterinary medicine as standard practice to provide optimum anesthetic induction. The onset or induction phase of anesthesia is a critical period involving the loss of consciousness and reactivity in the patient, and is arguably the most dangerous period of a general anesthetic. A great variety of coinduction combinations are in use and selection is dependent on the patient's age and health, the specific situation, and the indication for anesthesia. As with all forms of anesthesia the resources available in the environment are a key factor.

Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) refers to the intravenous administration of anesthetic agents to induce a temporary loss of sensation or awareness. The first study of TIVA was done in 1872 using chloral hydrate, and the common anesthetic agent propofol was licensed in 1986. TIVA is currently employed in various procedures as an alternative technique of general anesthesia in order to improve post-operative recovery.