Related Research Articles

The Pazyrykburials are a number of Saka Iron Age tombs found in the Pazyryk Valley of the Ukok plateau in the Altai Mountains, Siberia, south of the modern city of Novosibirsk, Russia; the site is close to the borders with China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Numerous comparable burials have been found in neighboring western Mongolia.

The Sarmatians were a large Iranian confederation that existed in classical antiquity, flourishing from about the 5th century BC to the 4th century AD.

A tumulus is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or kurgans, and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones built for various purposes, may also originally have been a tumulus.

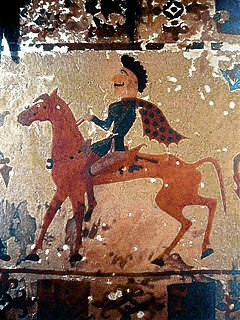

Scythian art is art, primarily decorative objects, such as jewellery, produced by the nomadic tribes in the area known to the ancient Greeks as Scythia, which was centred on the Pontic-Caspian steppe and ranged from modern Kazakhstan to the Baltic coast of modern Poland and to Georgia. The identities of the nomadic peoples of the steppes is often uncertain, and the term "Scythian" should often be taken loosely; the art of nomads much further east than the core Scythian territory exhibits close similarities as well as differences, and terms such as the "Scytho-Siberian world" are often used. Other Eurasian nomad peoples recognised by ancient writers, notably Herodotus, include the Massagetae, Sarmatians, and Saka, the last a name from Persian sources, while ancient Chinese sources speak of the Xiongnu or Hsiung-nu. Modern archaeologists recognise, among others, the Pazyryk, Tagar, and Aldy-Bel cultures, with the furthest east of all, the later Ordos culture a little west of Beijing. The art of these peoples is collectively known as steppes art.

Chariot burials are tombs in which the deceased was buried together with their chariot, usually including their horses and other possessions. An instance of a person being buried with their horse is called horse burial.

The Srubnaya culture, also known as Timber-grave culture, was a Late Bronze Age culture in the eastern part of Pontic-Caspian steppe. It is a successor to the Late Catacomb culture and the Poltavka culture, as well as the Potapovka culture.

The Trialeti culture, is named after the Trialeti region of Georgia. It is attributed to the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BC. Trialeti culture emerged in the areas of the preceding Kura-Araxes culture.

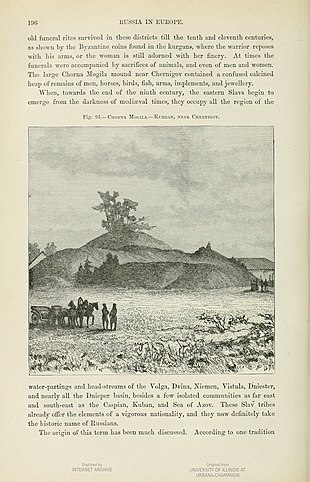

The Black Grave is the largest burial mound (kurgan) in Chernihiv, Ukraine. It is part of the National Sanctuary of Ancient Chernihiv and is an Archaeological Monument of national importance.

The Noin-Ula burial site consist of more than 200 large burial mounds, approximately square in plan, some 2 m in height, covering timber burial chambers. They are located by the Selenga River in the hills of northern Mongolia north of Ulan Bator in Batsumber sum of Tov Province. They were excavated in 1924–1925 by Pyotr Kozlov, who found them to be the tombs of the aristocracy of the Xiongnu; one is an exceptionally rich burial of a historically known ruler of the Xiongnu, Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy, who died in 13 CE. Most of the objects from Noin-Ula are now in the Hermitage Museum, while some artifacts unearthed later by Mongolian archaeologists are on display in the National Museum of Mongolian History, Ulan Bator. Two kurgans contained lacquer cups, inscribed with Chinese characters believed to be the names of Chinese craftsmen, and dated September 5 year of Tsian-ping era, i.e. 2nd year BCE.

The Prehistory of Siberia is marked by several archaeologically distinct cultures. In the Chalcolithic, the cultures of western and southern Siberia were pastoralists, while the eastern taiga and the tundra were dominated by hunter-gatherers until the late Middle Ages and even beyond. Substantial changes in society, economics and art indicate the development of nomadism in the Central Asian steppes in the first millennium BC.

The Taplow Barrow is an early medieval burial mound in Taplow Court, an estate in the south-eastern English county of Buckinghamshire. Constructed in the seventh century, when the region was part of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom, it contained the remains of a deceased individual and their grave goods, now mostly in the British Museum. It is often referred to in archaeology as the Taplow burial.

Burial in Early Anglo-Saxon England refers to the grave and burial customs followed by the Anglo-Saxons between the mid 5th and 11th centuries CE in Early Mediaeval England. There was "an immense range of variation" of burial practice performed by the Anglo-Saxon peoples during this period, with them making use of both cremation and inhumation. In most cases, the "two modes of burial were given to both wealthy and ordinary individuals", and in many cases were found alongside one another in the same cemetery. Both of these forms of burial were typically accompanied by grave goods, which included food, jewellery and weaponry. The actual burials themselves, whether of cremated or inhumed remains, were placed in a variety of sites, including in cemeteries, burial mounds or, more rarely, in ship burials.

The Siberian Ice Maiden, also known as the Princess of Ukok, the Altai Princess, Devochka and Ochy-bala, is a mummy of a woman from the 5th century BC, found in 1993 in a kurgan of the Pazyryk culture in Republic of Altai, Russia. It was among the most significant Russian archaeological findings of the late 20th century. In 2012 she was moved to a special mausoleum at the Republican National Museum in Gorno-Altaisk.

The Trumpington bed burial is an early Anglo-Saxon burial of a young woman, dating to the mid-7th century, that was excavated in Trumpington, Cambridgeshire, England in 2011. The burial is significant both as a rare example of a bed burial, and because of the ornate gold pectoral cross inlaid with garnets that was found in the grave.

The Aldy-Bel culture is an Iron Age culture of Scytho-Siberian horse nomads in the area of Tuva in southern Siberia, dated to the 7th to 3rd centuries BCE.

Begazy-Dandybai culture is Bronze Age culture of mixed economy in the territory of ancient central Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, dated from the 2nd millennium BCE to 8th century BCE, centered at (Sary-Arka) desert river. The culture, with its megalithic mausolea, flourished between the 12th and 8th centuries BCE. The culture was discovered, first excavated, and published in the 1930s-1940s by M.P. Gryaznov, who took it for a local version of Karasuk culture. In 1979 the Begazy-Dandybai culture was described and analyzed in detail in a monograph by A.Kh. Margulan, who systematically reviewed accumulated material and produced description of the archeological culture. The most famous monuments of Begazy-Dandybai culture are Begazy, Dandybai, Aksu Ayuly 2, Akkoytas, and Sangria 1.3, it was named after the first two archeological sites.

Irmen culture is an indigenous Late Bronze Age culture of animal breeders in the steppe and forest steppe area of the Ob river middle course, north of Altai in western Siberia, dated to around the 9th to 8th centuries BCE. Monuments of this advanced bronze-producing culture include numerous settlements and kurgan cemeteries, the culture was named after Irmen kurgan cemetery now flooded by Novosibirsk reservoir. Irmen culture was discovered and described by N.L.Chlenova in 1970.

Klin-Yar is a prehistoric and early medieval site in the North Caucasus, outside of Kislovodsk. It was first discovered in the 1980s. Archaeological excavations had uncovered settlement traces and extensive cemetery areas starting in the 8th century BC, belonging to the Koban culture. The site was used up to the 7th century AD. Its long use over all this period, its size and rich finds, as well as the data quality of recent excavations make Klin-Yar one of the most important archaeological sites of the region.

References

- Andrej B. Belinskij, Alexej A. Kalmykov, Sergej N. Korenevskij and Heinrich Harke, The Ipatovo kurgan on the North Caucasian Steppe, Antiquity, December 2000. (this link does not lead to the article!)