The Baroque is a Western style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from the early 17th century until the 1750s. It followed Renaissance art and Mannerism and preceded the Rococo and Neoclassical styles. It was encouraged by the Catholic Church as a means to counter the simplicity and austerity of Protestant architecture, art, and music, though Lutheran Baroque art developed in parts of Europe as well.

Rococo, less commonly Roccoco, also known as Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and dramatic style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, and trompe-l'œil frescoes to create surprise and the illusion of motion and drama. It is often described as the final expression of the Baroque movement.

Furniture refers to objects intended to support various human activities such as seating, eating (tables), storing items, working, and sleeping. Furniture is also used to hold objects at a convenient height for work, or to store things. Furniture can be a product of design and can be considered a form of decorative art. In addition to furniture's functional role, it can serve a symbolic or religious purpose. It can be made from a vast multitude of materials, including metal, plastic, and wood. Furniture can be made using a variety of woodworking joints which often reflects the local culture.

Ca' Rezzonico is a palazzo and art museum on the Grand Canal in the Dorsoduro sestiere of Venice, Italy. It is a particularly notable example of the 18th century Venetian baroque and rococo architecture and interior decoration, and displays paintings by the leading Venetian painters of the period, including Francesco Guardi and Giambattista Tiepolo. It is a public museum dedicated to 18th-century Venice and one of the 11 venues managed by the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

Liberty style was the Italian variant of Art Nouveau, which flourished between about 1890 and 1914. It was also sometimes known as stile floreale, arte nuova, or stile moderno. It took its name from Arthur Lasenby Liberty and the store he founded in 1874 in London, Liberty Department Store, which specialized in importing ornaments, textiles and art objects from Japan and the Far East. Major Italian designers using the style included Ernesto Basile, Ettore De Maria Bergler, Vittorio Ducrot, Carlo Bugatti, Raimondo D'Aronco, Eugenio Quarti, and Galileo Chini.

Sicilian Baroque is the distinctive form of Baroque architecture which evolved on the island of Sicily, off the southern coast of Italy, in the 17th and 18th centuries, when it was part of the Spanish Empire. The style is recognisable not only by its typical Baroque curves and flourishes, but also by distinctive grinning masks and putti and a particular flamboyance that has given Sicily a unique architectural identity.

Rocaille was a French style of exuberant decoration, with an abundance of curves, counter-curves, undulations and elements modeled on nature, that appeared in furniture and interior decoration during the early reign of Louis XV of France. It was a reaction against the heaviness and formality of the Louis XIV style. It began in about 1710, reached its peak in the 1730s, and came to an end in the late 1750s, replaced by Neoclassicism. It was the beginning of the French Baroque movement in furniture and design, and also marked the beginning of the Rococo movement, which spread to Italy, Bavaria and Austria by the mid-18th century.

The Louis XV style or Louis Quinze is a style of architecture and decorative arts which appeared during the reign of Louis XV. From 1710 until about 1730, a period known as the Régence, it was largely an extension of the Louis XIV style of his great-grandfather and predecessor, Louis XIV. From about 1730 until about 1750, it became more original, decorative and exuberant, in what was known as the Rocaille style, under the influence of the King's mistress, Madame de Pompadour. It marked the beginning of the European Rococo movement. From 1750 until the King's death in 1774, it became more sober, ordered, and began to show the influences of Neoclassicism.

Palazzo Valguarnera-Gangi is an urban palace, first of the Princes Valguarnera and then of the Princes Gangi, situated in the Piazza Croce dei Vespri, in the ancient quarter of the Kalsa in the city of Palermo, region of Sicily, Italy. The palace still retains its original rich Rococo interior decoration, and is located a block south of the church of Sant'Anna la Misericordia.

A cabriole leg is one of (usually) four vertical supports of a piece of furniture shaped in two curves; the upper arc is convex, while lower is concave; the upper curve always bows outward, while the lower curve bows inward; with the axes of the two curves in the same plane. This design was used by the ancient Chinese and Greeks, but emerged in Europe in the very early 18th century, when it was incorporated into the more curvilinear styles produced in France, England and Holland.

French architecture consists of architectural styles that either originated in France or elsewhere and were developed within the territories of France.

The forms of Chinese furniture evolved along three distinct lineages which date back to 1000 BC: frame and panel, yoke and rack and bamboo construction techniques. Chinese home furniture evolved independently of Western furniture into many similar forms, including chairs, tables, stools, cupboards, cabinets, beds and sofas. Until about the 10th century CE, the Chinese sat on mats or low platforms using low tables, but then gradually moved to using high tables with chairs.

The Queen Anne style of furniture design developed before, during, and after the time of Queen Anne, who reigned from 1702 to 1714.

Italian Baroque architecture refers to Baroque architecture in Italy.

Italian Baroque interior design refers to high-style furnishing and interior decorating carried out in Italy during the Baroque period, which lasted from the early 17th to the mid-18th century. In provincial areas, Baroque forms such as the clothes-press or armadio continued to be used into the 19th century.

Italian Neoclassical interior design refers to furnishing and interior decorating trends in Italy which occurred during the Neoclassical period

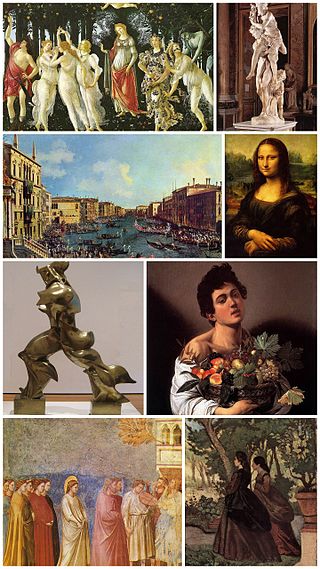

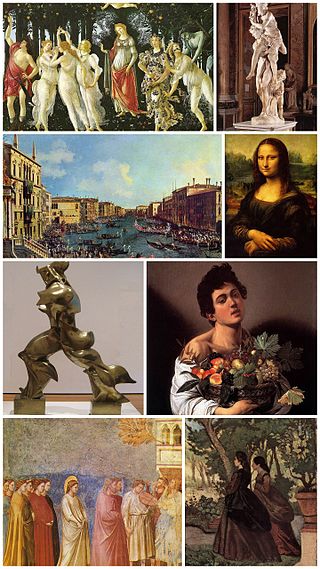

The 1700s refers to a period in Italian history and culture which occurred during the 18th century (1700–1799): the Settecento. The Settecento saw the transition from Late Baroque to Neoclassicism: great artists of this period include Vanvitelli, Canaletto and Canova, as well as the composer Vivaldi and the writer Goldoni.

The Rococo Revival style emerged in Britain and France in the 19th century. Revival of the rococo style was seen all throughout Europe during the 19th century within a variety of artistic modes and expression including decorative objects of art, paintings, art prints, furniture, and interior design. In much of Europe and particularly in France, the original rococo was regarded as a national style, and to many, its reemergence recalled national tradition. Rococo revival epitomized grandeur and luxury in European style and was another expression of 19th century romanticism and the growing interest and fascination with natural landscape.

The Spanish Rococo style of the 18th century is relatively unexplored and bears little resemblance to its French equivalent. Under the reign of Philip V of the Bourbon Dynasty, architectural commissions were primarily awarded to Italian architects, rather than the French who were the pioneers of the rococo style. This is largely due to the influence of his second wife, Elisabeth Farnese of Parma, who aimed to transcend French influence through the promotion of the Italians. Consequently, Rococo was left to be discovered by the Spanish school and therefore evolved separately from French and other variations of Rococo.

The furniture of the Louis XV period (1715–1774) is characterized by curved forms, lightness, comfort and asymmetry; it replaced the more formal, boxlike and massive furniture of the Louis XIV style. It employed marquetry, using inlays of exotic woods of different colors, as well as ivory and mother of pearl.