Related Research Articles

A documentary film is a non-fictional motion picture intended to "document reality, primarily for instruction, education or maintaining a historical record". The American author and media analyst Bill Nichols has characterized the documentary in terms of "a filmmaking practice, a cinematic tradition, and mode of audience reception [that remains] a practice without clear boundaries".

Cinéma vérité is a style of documentary filmmaking developed by Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch, inspired by Dziga Vertov's theory about Kino-Pravda. It combines improvisation with use of the camera to unveil truth or highlight subjects hidden behind reality. It is sometimes called observational cinema, if understood as pure direct cinema: mainly without a narrator's voice-over. There are subtle, yet important, differences between terms expressing similar concepts. Direct cinema is largely concerned with the recording of events in which the subject and audience become unaware of the camera's presence: operating within what Bill Nichols, an American historian and theoretician of documentary film, calls the "observational mode", a fly on the wall. Many therefore see a paradox in drawing attention away from the presence of the camera and simultaneously interfering in the reality it registers when attempting to discover a cinematic truth.

Jean Rouch was a French filmmaker and anthropologist.

Direct cinema is a documentary genre that originated between 1958 and 1962 in North America—principally in the Canadian province of Quebec and in the United States—and was developed in France by Jean Rouch. It is a cinematic practice employing lightweight portable filming equipment, hand-held cameras and live, synchronous sound that became available because of new, ground-breaking technologies developed in the early 1960s. These innovations made it possible for independent filmmakers to do away with a truckload of optical sound-recording, large crews, studio sets, tripod-mounted equipment and special lights, expensive necessities that severely hog-tied these low-budget documentarians. Like the cinéma vérité genre, direct cinema was initially characterized by filmmakers' desire to capture reality directly, to represent it truthfully, and to question the relationship between reality and cinema.

Cinema of Africa covers both the history and present of the making or screening of films on the African continent, and also refers to the persons involved in this form of audiovisual culture. It dates back to the early 20th century, when film reels were the primary cinematic technology in use. As there are more than 50 countries with audiovisual traditions, there is no one single 'African cinema'. Both historically and culturally, there are major regional differences between North African and sub-Saharan cinemas, and between the cinemas of different countries.

The Margaret Mead Film Festival is an annual film festival held at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. It is the longest-running, premiere showcase for international documentaries in the United States, encompassing a broad spectrum of work, from indigenous community media to experimental nonfiction. The Festival is distinguished by its outstanding selection of titles, which tackle diverse and challenging subjects, representing a range of issues and perspectives, and by the forums for discussion with filmmakers and speakers.

Oumarou Ganda was a Nigerien director and actor who helped bring African cinema to international attention in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Cinema of Niger began in the 1940s with the ethnographical documentary of French director Jean Rouch, before growing to become one of the most active national film cultures in Francophone Africa in the 1960s-70s with the work of filmmakers such as Oumarou Ganda, Moustapha Alassane and Gatta Abdourahamne. The industry has slowed somewhat since the 1980s, though films continue to be made in the country, with notable directors of recent decades including Mahamane Bakabe, Inoussa Ousseini, Mariama Hima, Moustapha Diop and Rahmatou Keïta. Unlike neighbouring Nigeria, with its thriving Hausa and English-language film industries, most Nigerien films are made in French with Francophone countries as their major market, whilst action and light entertainment films from Nigeria or dubbed western films fill most Nigerien theatres.

![<i>Les maîtres fous</i> 1955 [[Cinema of France|France]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/6/68/Les_maitres_fous_title_still.jpg/320px-Les_maitres_fous_title_still.jpg)

Les maîtres fous is a 1955 short film directed by Jean Rouch, a well-known French film director and ethnologist. It is a docufiction, his first ethnofiction, a genre he is considered to have created.

Ethnofiction refers to a subfield of ethnography which produces works that introduce art, in the form of storytelling, "thick descriptions and conversational narratives", and even first-person autobiographical accounts, into peer-reviewed academic works.

An ethnographic film is a non-fiction film, often similar to a documentary film, historically shot by Western filmmakers and dealing with non-Western people, and sometimes associated with anthropology. Definitions of the term are not definitive. Some academics claim it is more documentary, less anthropology, while others think it rests somewhere between the fields of anthropology and documentary films.

Safi Faye was a Senegalese film director and ethnologist. She was the first Sub-Saharan African woman to direct a commercially distributed feature film, Kaddu Beykat, which was released in 1975. She has directed several documentary and fiction films focusing on rural life in Senegal.

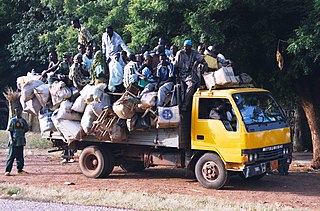

Seasonal migration, locally called the Exode, plays an important part of the economic and cultural life of the West African nation of Niger. While it is a common practice in many nations, Niger sees as much as a third of its rural population travel for seasonal labour, during the Sahelian nation's long dry season. Common patterns of seasonal travel have been built up over hundreds of years, and destinations and work vary by community and ethnic group.

Damouré Zika was a Nigerien traditional healer, broadcaster, and film actor. Coming from a long line of traditional healers in the Sorko ethnic group of western Niger, Zika appeared in many of the films of French director Jean Rouch, becoming one of Niger's first actors. As a practitioner of traditional medicine, he opened a clinic in Niamey, and was for many years a broadcaster and commentator on health issues for Niger's national radio.

Cinéma du Réel is an international documentary film festival organized by the BPI-Bibliothèque publique d'information in Paris and was founded in 1978. The festival presents about 200 films per year in several sections by experienced documentary directors as well as first timers. The screenings take place at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and in several movie theaters partners of the festival.

Documentary mode is a conceptual scheme developed by American documentary theorist Bill Nichols that seeks to distinguish particular traits and conventions of various documentary film styles. Nichols identifies six different documentary 'modes' in his schema: poetic, expository, observational, participatory, reflexive, and performative. While Nichols' discussion of modes does progress chronologically with the order of their appearance in practice, documentary film often returns to themes and devices from previous modes. Therefore, it is inaccurate to think of modes as historical punctuation marks in an evolution towards an ultimate accepted documentary style. Also, modes are not mutually exclusive. There is often significant overlapping between modalities within individual documentary features. As Nichols points out, "the characteristics of a given mode function as a dominant in a given film…but they do not dictate or determine every aspect of its organization."

Ethnocinema, from Jean Rouch’s cine-ethnography and ethno-fictions, is an emerging practice of intercultural filmmaking being defined and extended by Melbourne, Australia-based writer and arts educator, Anne Harris, and others. Originally derived from the discipline of anthropology, ethnocinema is one form of ethnographic filmmaking that prioritises mutuality, collaboration and social change. The practice's ethos claims that the role of anthropologists, and other cultural, media and educational researchers, must adapt to changing communities, transnational identities and new notions of representation for the 21st century.

Moi, un noir is a 1958 French ethnofiction film directed by Jean Rouch. The film is set in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

Paul Stoller is an American cultural anthropologist. He is a professor of anthropology at West Chester University in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

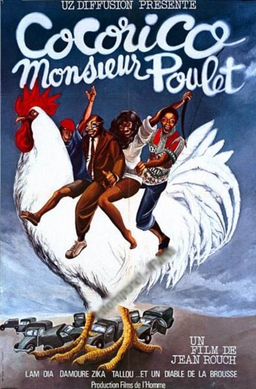

Cocorico! Monsieur Poulet is a 1977 Franco-Nigerien road movie by "Dalarou", a pseudonym for Damouré Zika, Lam Ibrahim Dia and Jean Rouch.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Stoller, Paul (1992). The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch. University of Chicago Press. pp. 138–143. ISBN 0226775488.

- 1 2 Ginsburg, Faye (Fall 1995). "The Parallax Effect: The Impact of Aboriginal Media on Ethnographic Film" (PDF). Visual Anthropology Review. 11 (2): 67. doi:10.1525/var.1995.11.2.64.

- 1 2 3 Henley, Paul (2010). The Adventure of the Real: Jean Rouch and the Craft of Ethnographic Cinema. University of Chicago Press. pp. 73, 74, 81. ISBN 978-0226327167.