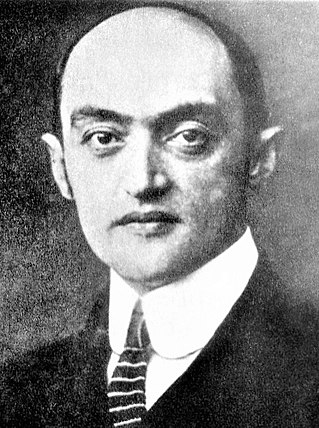

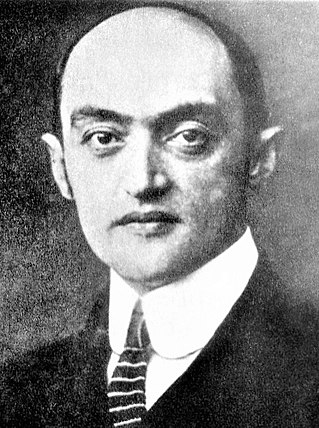

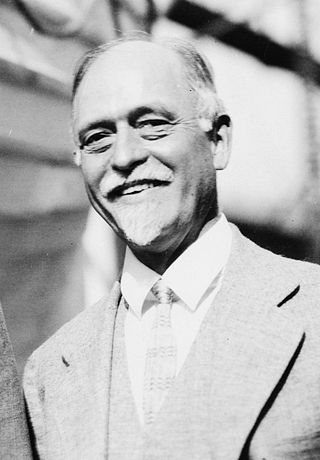

Joseph Alois Schumpeter was an Austrian political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at Harvard University, where he remained until the end of his career, and in 1939 obtained American citizenship.

James Tobin was an American economist who served on the Council of Economic Advisers and consulted with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and taught at Harvard and Yale Universities. He contributed to the development of key ideas in the Keynesian economics of his generation and advocated government intervention in particular to stabilize output and avoid recessions. His academic work included pioneering contributions to the study of investment, monetary and fiscal policy and financial markets. He also proposed an econometric model for censored dependent variables, the well-known tobit model.

Keynesian economics are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. Instead, it is influenced by a host of factors – sometimes behaving erratically – affecting production, employment, and inflation.

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption, and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good or service is determined through a hypothetical maximization of utility by income-constrained individuals and of profits by firms facing production costs and employing available information and factors of production. This approach has often been justified by appealing to rational choice theory, a theory that has come under considerable question in recent years.

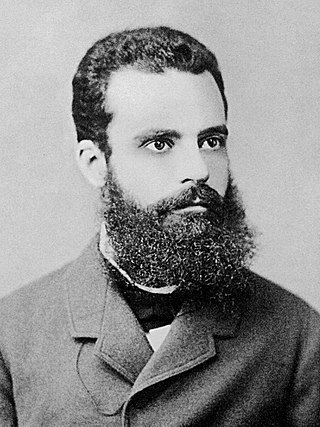

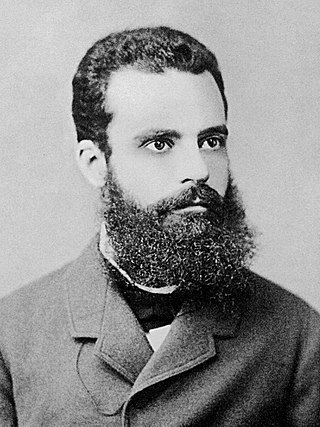

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto was an Italian polymath. He made several important contributions to economics, particularly in the study of income distribution and in the analysis of individuals' choices. He was also responsible for popularising the use of the term "elite" in social analysis.

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national output in the short run and on price levels over longer periods. Monetarists assert that the objectives of monetary policy are best met by targeting the growth rate of the money supply rather than by engaging in discretionary monetary policy. Monetarism is commonly associated with neoliberalism.

Franco Modigliani was an Italian-American economist and the recipient of the 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. He was a professor at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Carnegie Mellon University, and MIT Sloan School of Management.

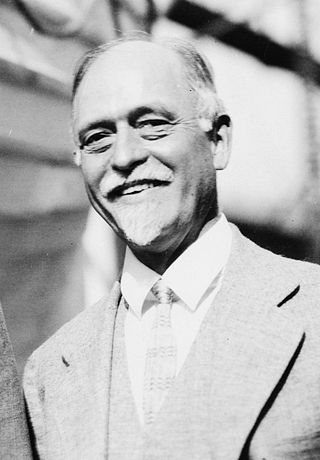

Irving Fisher was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt deflation has been embraced by the post-Keynesian school. Joseph Schumpeter described him as "the greatest economist the United States has ever produced", an assessment later repeated by James Tobin and Milton Friedman.

The Chicago school of economics is a neoclassical school of economic thought associated with the work of the faculty at the University of Chicago, some of whom have constructed and popularized its principles. Milton Friedman and George Stigler are considered the leading scholars of the Chicago school.

Lauchlin Bernard Currie was an economist who worked as White House economic adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt during World War II (1939–45). From 1949 to 1953, he directed a major World Bank mission to Colombia and related studies.

John Brian Taylor is the Mary and Robert Raymond Professor of Economics at Stanford University, and the George P. Shultz Senior Fellow in Economics at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

Edmund Strother Phelps is an American economist and the recipient of the 2006 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Heterodox economics is any economic thought or theory that contrasts with orthodox schools of economic thought, or that may be beyond neoclassical economics. These include institutional, evolutionary, feminist, social, post-Keynesian, ecological, Austrian, complexity, Marxian, socialist, and anarchist economics.

Alvin Harvey Hansen was an American economist who taught at the University of Minnesota and was later a chair professor of economics at Harvard University. Often referred to as "the American Keynes", he was a widely read popular author on economic issues, and an influential advisor to the government on economic policy. Hansen helped create the Council of Economic Advisors and the Social Security system. He is best remembered today for introducing Keynesian economics in the United States in the 1930s and 40s.

The Lausanne School of economics, sometimes referred to as the Mathematical School, refers to the neoclassical economics school of thought surrounding Léon Walras and Vilfredo Pareto. It is named after the University of Lausanne, at which both Walras and Pareto held professorships. Polish economist Leon Winiarski is also said to have been a member of the Lausanne School.

Applied economics is the study as regards the application of economic theory and econometrics in specific settings. As one of the two sets of fields of economics, it is typically characterized by the application of the core, i.e. economic theory and econometrics to address practical issues in a range of fields including demographic economics, labour economics, business economics, industrial organization, agricultural economics, development economics, education economics, engineering economics, financial economics, health economics, monetary economics, public economics, and economic history. From the perspective of economic development, the purpose of applied economics is to enhance the quality of business practices and national policy making.

In the history of economic thought, a school of economic thought is a group of economic thinkers who share or shared a common perspective on the way economies work. While economists do not always fit into particular schools, particularly in modern times, classifying economists into schools of thought is common. Economic thought may be roughly divided into three phases: premodern, early modern and modern. Systematic economic theory has been developed mainly since the beginning of what is termed the modern era.

Paul Davidson is an American macroeconomist who has been one of the leading spokesmen of the American branch of the post-Keynesian school in economics. He is a prolific writer and has actively intervened in important debates on economic policy from a position critical of mainstream economics.

Warren Joseph Samuels was an American economist and historian of economic thought. He received a BBA from University of Miami, Miami, FL and obtained his Ph.D. from University of Wisconsin–Madison. After holding academic posts in the University of Missouri, Georgia State University, Atlanta, and University of Miami, he was appointed Professor of Economics in Michigan State University in 1968, where he stayed until his retirement in 1998.

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.