Related Research Articles

Babylonian law is a subset of cuneiform law that has received particular study due to the large amount of archaeological material that has been found for it. So-called "contracts" exist in the thousands, including a great variety of deeds, conveyances, bonds, receipts, accounts, and most important of all, actual legal decisions given by the judges in the law courts. Historical inscriptions, royal charters and rescripts, dispatches, private letters and the general literature afford welcome supplementary information. Even grammatical and lexicographical texts contain many extracts or short sentences bearing on law and custom. The so-called "Sumerian Family Laws" are preserved in this way.

Northampton County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 12,389. Its county seat is Eastville. Northampton and Accomack Counties are a part of the larger Eastern Shore of Virginia.

Eleanor Butler was an indentured white woman who married an enslaved African man in colonial Maryland in 1681.

In societies that regard some races or ethnic groups of people as dominant or superior and others as subordinate or inferior, hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment by the dominant culture of children of a mixed union or sexual relations between members of different socioeconomic groups or ethnic groups to the subordinate group. The opposite practice is hyperdescent, in which children are assigned to the race that is considered dominant or superior.

In the history of slavery, the legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was used from 1662 in Virginia and later other English royal colonies to establish the legal status of children born there; they were considered to follow the status of their mothers. Therefore, children of enslaved women were born into slavery; those born to free white women were born free. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem derived from Roman civil law, which concerned personal property (chattels).

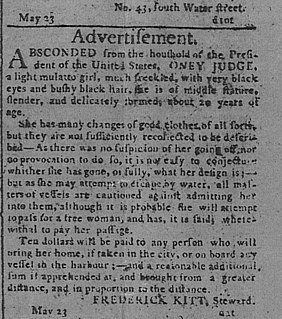

Ona "Oney" Judge Staines was a woman of mixed races who was enslaved to the Washington family, first at the family's plantation at Mount Vernon and later, after George Washington became president, at the President's House in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital city. At the age of 23, she absconded, becoming a fugitive slave, after learning that Martha Washington had intended to transfer ownership of her to her niece, known to have a horrible temper, and fled to New Hampshire, where she married, had children, and converted to Christianity. Though she was never freed, the Washington family did not want to risk public backlash in forcing her to return to Virginia and after so many years of failing to persuade her to return quietly, the family let her be.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Virginia Colony, in 1655 became the first person of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be declared as a slave for life as a result of a civil suit. In an earlier case, John Punch was the first man documented as a slave in the Virginia Colony, sentenced to life in servitude for attempting to escape his captors.

Anthony Johnson was a black Angolan known for achieving wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. He was one of the first African American property owners and had his right to legally own a slave recognized by the Virginia courts. Held as an indentured servant in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years, and was granted land by the colony.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported African slaves for workers; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Slavery was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled Pennsylvania tolerated slavery, but the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (Greenstead) was one of the first black people of the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Elizabeth Key won her freedom and that of her infant son John Grinstead on July 21, 1656 in the colony of Virginia. Key based her suit on the fact that her father was an Englishman who had acknowledged her and arranged her baptism as a Christian in the American branch of the Church of England. He was a wealthy planter who had tried to protect her by establishing a guardianship for her when she was young, before his death. Based on these factors, her attorney and common-law husband, William Grinstead argued successfully that she should be freed. The lawsuit was one of the earliest "freedom suits" by an African-descended person in the English colonies.

Slavery in Virginia began with the enslavement of Native Americans, during the early days of the Colony of Virginia and through the late 18th century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to Colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia on the ship The White Lion. About that time, Native Americans were also captured and enslaved.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by enslaved people against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

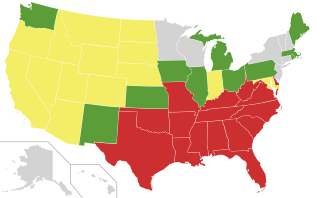

In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws were laws passed by most states that prohibited interracial marriage and interracial sexual relations. Some such laws predate the establishment of the United States, some dating to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery. Most states had repealed such laws by 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that such laws were unconstitutional in the remaining 16 states. The term miscegenation was first used in 1863, during the American Civil War, by journalists to discredit the abolitionist movement by stirring up debate over the prospect of interracial marriage after the abolition of slavery.

John Punch was an enslaved African who lived in the colony of Virginia. Thought to have been an indentured servant, Punch attempted to escape to Maryland and was sentenced in July 1640 by the Virginia Governor's Council to serve as a slave for the remainder of his life. Two European men who ran away with him received a lighter sentence of extended indentured servitude. For this reason, historians consider John Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies," and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake." Historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony, and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in The British Colonies.

Anne Orthwood's bastard trial took place in 1663 in the then relatively new royal Colony of Virginia. Anne Orthwood was a 24-year-old maidservant when she became pregnant with her illegitimate twins. The father was the nephew of a powerful Virginian politician who felt that Anne's pregnancy would tarnish his family's reputation. Anne Orthwood died during childbirth, leaving behind her only surviving son, Jasper, with no one willing to claim him as their own. The four different cases that stem from the original trial of Anne Orthwood give a glimpse into the world of America in the seventeenth century as well as highlight the reasons legal systems are created in the first place.

Indentured servitude in continental North America began in the Colony of Virginia in 1609. Initially created as means of funding voyages for European workers to the New World, the institution dwindled over time as the labor force was replaced with enslaved Africans. Servitude became a central institution in the economy and society of many parts of colonial British America. Abbot Emerson Smith, a leading historian of indentured servitude during the colonial period, estimated that between one-half and two-thirds of all white immigrants to the British colonies between the Puritan migration of the 1630s and the American Revolution came under indenture. For the colony of Virginia, specifically, more than two-thirds of all white immigrants arrived as indentured servants or transported convict bond servants.

Indentured servitude in British America was the prominent system of labor in British American colonies until it was eventually overcome by slavery. During its time, the system was so prominent that more than half of all immigrants to British colonies south of New England were white servants, and that nearly half of total white immigration to the Thirteen Colonies came under indenture. By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial labor force was composed of indentured servants.

Gabriel Jacobs, born about 1650, was the progenitor of the Jacobs family of free African Americans originating in Northampton County, Virginia. A number of his descendants migrated south in the mid-1700s, primarily to southeastern North Carolina. His story and that of his descendants is representative of the experiences of hundreds of other freedmen originating in early southern American colonies.

John Graweere also known as John Gowen was one of the First Africans in Virginia, who was a servant who earned enough money to pay for his son's freedom. He filed a lawsuit to free his son, arguing that he wanted to raise him as a Christian. The court agreed and freed the son.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Crawford, Greg (2012-11-14). "You Have No Right: Jane Webb's Story". The UncommonWealth, Library of Virginia. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Snyder, Terri L. (2012). "Marriage on the Margins: Free Wives, Enslaved Husbands, and the Law in Early Virginia". Law and History Review. 30 (1): 141–171. ISSN 0738-2480.