Slavery in the colonial history of the United States refers to the institution of slavery as it existed in the European colonies which eventually became part of the United States. In these colonies, slavery developed due to a combination of factors, primarily the labour demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies, which had resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were victims of enslavement by European colonizers during the era.

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, or it may be imposed "involuntarily" as a judicial punishment. Historically, it has been used to pay for apprenticeships, typically when an apprentice agreed to work for free for a master tradesman to learn a trade. Later it was also used as a way for a person to pay the cost of transportation to colonies in the Americas.

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

The Barbados Slave Code of 1661, officially titled as An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes, was a law passed by the Parliament of Barbados to provide a legal basis for slavery in the English colony of Barbados. It is the first comprehensive Slave Act, and the code's preamble, which stated that the law's purpose was to "protect them [slaves] as we do men's other goods and Chattels", established that black slaves would be treated as chattel property in the island's court.

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans. In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political privileges, between free white persons and free colored persons of African blood; and in no part of the country do the latter, in point of fact, participate equally with the whites, in the exercise of civil and political rights." Although Black Codes existed before the Civil War and although many Northern states had them, the Southern U.S. states codified such laws in everyday practice. The best known of these laws were passed by Southern states in 1865 and 1866, after the Civil War, in order to restrict African Americans' freedom, and in order to compel them to work for either low or no wages.

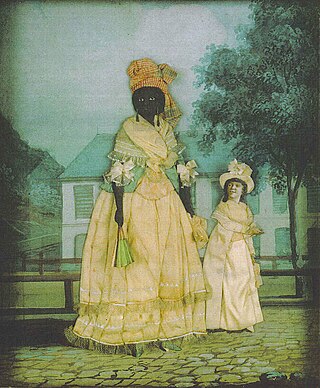

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free.

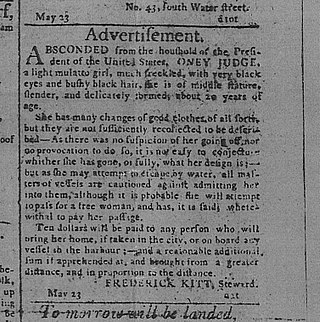

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from the Fugitive Slave Clause which is in the United States Constitution. It was thought that forcing states to deliver fugitive slaves back to enslavement violated states' rights due to state sovereignty and was believed that seizing state property should not be left up to the states. The Fugitive Slave Clause states that fugitive slaves "shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due", which abridged state rights because forcing people back into slavery was a form of retrieving private property. The Compromise of 1850 entailed a series of laws that allowed slavery in the new territories and forced officials in free states to give a hearing to slave-owners without a jury.

In societies that regard some races or ethnic groups of people as dominant or superior and others as subordinate or inferior, hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union to the subordinate group. The opposite practice is hyperdescent, in which children are assigned to the race that is considered dominant or superior.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of slave mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Virginia Colony, in 1655 became the first person of African descent and second person in the Thirteen Colonies to be declared as a slave for life as a result of a civil suit. In 1662, the Virginia Colony passed a law incorporating the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, ruling that children of enslaved mothers would be born into slavery, regardless of their father's race or status. This was in contradiction to English common law for English subjects, which based a child's status on that of the father. In 1699 the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law deporting all free black people. But many new families of free black people continued to be formed during the colonial years by the close relationships among the working class.

Anthony Johnson was an Angolan-born man who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. Held as an indentured servant in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years, and was granted land by the colony.

Slavery was practiced in Massachusetts bay by Native Americans before European settlement, and continued until its abolition in the 1700s. Although slavery in the United States is typically associated with the Caribbean and the Antebellum American South, enslaved existed to a lesser extent in New England: historians estimate that between 1755 and 1764, the Massachusetts enslaved population was approximately 2.2 percent of the total population; the slave population was generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns. Unlike in the American South, enslaved people in Massachusetts had legal rights, including the ability to file legal suits in court.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free people their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (or Greenstead) (1630 – January 20, 1665) was one of the first black people of the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son John Grinstead on July 21, 1656, in the colony of Virginia.

Slavery among Native Americans in the United States includes slavery by and slavery of Native Americans roughly within what is currently the United States of America.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

John Punch was an enslaved African who lived in the colony of Virginia. Thought to have been an indentured servant, Punch attempted to escape to Maryland and was sentenced in July 1640 by the Virginia Governor's Council to serve as a slave for the remainder of his life. Two European men who ran away with him received a lighter sentence of extended indentured servitude. For this reason, some historians consider John Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies," and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake." Some historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony, and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in the United States.

Indentured servitude in British America was the prominent system of labor in the British American colonies until it was eventually supplanted by slavery. During its time, the system was so prominent that more than half of all immigrants to British colonies south of New England were white servants, and that nearly half of total white immigration to the Thirteen Colonies came under indenture. By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial labor force was composed of indentured servants.

Polly Strong was an enslaved woman in the Northwest Territory, in present-day Indiana. She was born after the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery. Slavery was prohibited by the Constitution of Indiana in 1816. Two years later, Strong's mother Jenny and attorney Moses Tabbs asked for a writ of habeas corpus for Polly and her brother James in 1818. Judge Thomas H. Blake produced indentures, Polly for 12 more years and James for four more years of servitude. The case was dismissed in 1819.