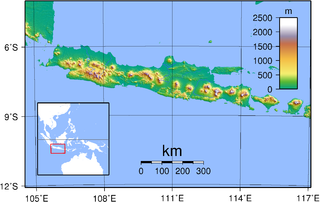

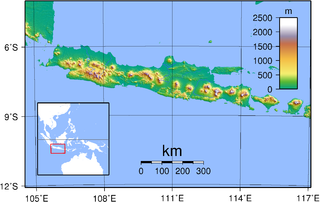

Java is one of the islands of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia, bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea on the north. With a population of over 148 million or 152 million, Java constitutes 56.1 percent of the Indonesian population and is the world's most-populous island. The Indonesian capital city, Jakarta, is on its northwestern coast. Much of the well-known part of Indonesian history took place on Java. It was the centre of powerful Hindu-Buddhist empires, the Islamic sultanates, and the core of the colonial Dutch East Indies. Java was also the center of the Indonesian struggle for independence during the 1930s and 1940s. Java dominates Indonesia politically, economically and culturally. Four of Indonesia's eight UNESCO world heritage sites are located in Java: Ujung Kulon National Park, Borobudur Temple, Prambanan Temple, and Sangiran Early Man Site.

Semarang is the capital and largest city of Central Java province in Indonesia. It was a major port during the Dutch colonial era, and is still an important regional center and port today. The city has been named as the cleanest tourist destination in Southeast Asia by the ASEAN Clean Tourist City Standard (ACTCS) for 2020–2022.

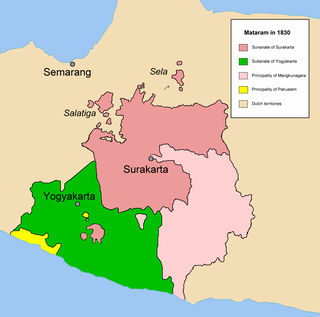

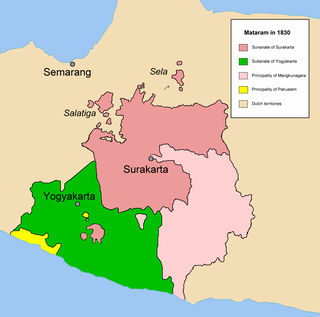

The Sultanate of Mataram was the last major independent Javanese kingdom on the island of Java before it was colonised by the Dutch. It was the dominant political force radiating from the interior of Central Java from the late 16th century until the beginning of the 18th century.

Priyayi was the Dutch-era class of the nobles of the robe, as opposed to royal nobility or ningrat (Javanese), in Java, Indonesia's most populous island.

The Merdeka Palace, is one of six presidential palaces in Indonesia. It is located on the north side of the Merdeka Square in Central Jakarta, Indonesia and is used as the official residence of the President of the Republic of Indonesia.

Sultan Hanyakrakusuma is known as Sultan Agung was the third Sultan of Mataram in Central Java ruling from 1613 to 1645. A skilled soldier he conquered neighbouring states and expanded and consolidated his kingdom to its greatest territorial and military power.

A regency is a second-level administrative division of Indonesia, directly administrated under a province. The Indonesian term kabupaten is also sometimes translated as "municipality". Regencies and cities are divided into districts.

The Sultanate of Yogyakarta is a Javanese monarchy in Yogyakarta Special Region, in the Republic of Indonesia. The current head of the Sultanate is Hamengkubuwono X.

Hamengkubuwono I, born Raden Mas Sujana, was the first sultan of Yogyakarta, reigning between 1755 and 1792.

The Vorstenlanden were four native, princely states on the island of Java in the colonial Dutch East Indies. They were nominally self-governing vassals under suzerainty of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Their political autonomy however became increasingly constrained by severe treaties and settlements. Two of these continues to exist as a princely territory within the current independent republic of Indonesia.

Yogyakarta is the capital city of Special Region of Yogyakarta in Indonesia, on the island of Java. As the only Indonesian royal city still ruled by a monarchy, Yogyakarta is regarded as an important centre for classical Javanese fine arts and culture such as ballet, batik textiles, drama, literature, music, poetry, silversmithing, visual arts, and wayang puppetry. Renowned as a centre of Indonesian education, Yogyakarta is home to a large student population and dozens of schools and universities, including Gadjah Mada University, the country's largest institute of higher education and one of its most prestigious.

Amangkurat I was the sultan of Mataram from 1646 to 1677. He was the son of Sultan Agung Hanyokrokusumo. He experienced many rebellions during his reign. He died in exile in 1677, and buried in Tegalwangi, hence his posthumous title, Sunan Tegalwangi or Sunan Tegalarum. He was also nicknamed as Sunan Getek, because he was wounded when suppressing the rebellion of Raden Mas Alit, his own brother.

Kediri is an Indonesian city, located near the Brantas River in the province of East Java on the island of Java. It covers an area of 63.40 km2 and had a population of 268,950 at the 2010 Census; the latest official estimate is 294,950. It is one of two 'Daerah Tingkat II' that have the name 'Kediri'. The city is administratively separated from the Regency, of which it was formerly the capital.

The architecture of Indonesia reflects the diversity of cultural, historical and geographic influences that have shaped Indonesia as a whole. Invaders, colonizers, missionaries, merchants and traders brought cultural changes that had a profound effect on building styles and techniques.

Pakubuwono XI was the eleventh Susuhunan during the Second World War – and during Japanese occupation of Java.

The Dutch East India Company had a presence in the Malay archipelago from 1610, when the first trading post was established, to 1800, when the bankrupt company was dissolved, and its possessions nationalised as the Dutch East Indies.

Surakarta Sunanate was a Javanese monarchy centred in the city of Surakarta, in the province of Central Java, Indonesia.

Madiun Regency is a Regency in East Java province, Indonesia. It covers an area of 1,037.58 km2, and had a population of 662,278 at the 2010 Census; the latest official estimate is 681,394. It is bordered by Bojonegoro Regency in the north, Nganjuk Regency in the east, Ponorogo Regency in the south, and Magetan Regency and Ngawi Regency in the west, while the city of Madiun is an enclave within the regency.

French and British interregnum in the Dutch East Indies were a relatively short period of French and followed by British interregnum on the Dutch East Indies that took place between 1806 and 1815. The French ruled between 1806 and 1811. The British took over for 1811 to 1815, and transferred its control back to the Dutch in 1815.

The archaeology of Indonesia is the study of the archaeology of the archipelagic realm that today forms the nation of Indonesia, stretching from prehistory through almost two millennia of documented history. The ancient Indonesian archipelago was a geographical maritime bridge between the political and cultural centers of Ancient India and Imperial China, and is notable as a part of ancient Maritime Silk Road.