Related Research Articles

Tucson is a city in and the county seat of Pima County, Arizona, United States, and is home to the University of Arizona. It is the second-largest city in Arizona behind Phoenix, with a population of 542,629 in the 2020 United States census, while the population of the entire Tucson metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is 1,043,433. The Tucson MSA forms part of the larger Tucson-Nogales combined statistical area. Both Tucson and Phoenix anchor the Arizona Sun Corridor. The city is 108 miles (174 km) southeast of Phoenix and 60 mi (100 km) north of the United States–Mexico border.

Raúl Manuel Grijalva is an American politician and activist who has served as the United States representative for Arizona's 7th congressional district since 2023 and Arizona's 3rd congressional district from 2003 to 2023. He is a member of the Democratic Party. The district was numbered as the 7th from 2003 to 2013 and includes the western third of Tucson, part of Yuma and Nogales, and some peripheral parts of metro Phoenix. Grijalva is the dean of Arizona's congressional delegation.

Hi Corbett Field is a baseball park in the southwestern United States, located in Tucson, Arizona. With a seating capacity of approximately 9,500, it was the spring training home of the Colorado Rockies and Cleveland Indians of Major League Baseball, and is currently home to the University of Arizona Wildcats of the Big 12 Conference.

The Tucson Toros were a professional baseball team based in Tucson, Arizona, in the United States.

El Con Center is an open-air shopping mall in the city of Tucson, Arizona, United States anchored by Cinemark Theatres, Target, The Home Depot, Walmart, Ross (30,220 ft.2), Burlington (65,680 ft.2), and Marshalls. There is 1 vacant anchor store that was once JCPenney. The oldest mall in metropolitan Tucson, El Con Mall, as it was known since its opening in 1960, was renamed in May 2014 at the time of its sale for $81.7 million to Stan Kroenke, owner of numerous sports properties including Arsenal F.C. and the Los Angeles Rams.

Pete Hershberger is an American politician who served as a member of the Arizona House of Representatives, representing the 26th District from 2001 to 2008. He previously served in the State House, representing the 12th District from 1983 to 1985.

This is a list of the National Register of Historic Places listings in Pima County, Arizona.

Pima County Courthouse is the former main county courthouse building in downtown Tucson, Arizona It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was designed by Roy Place in 1928 in Mission Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival style architecture.

Old Main, University of Arizona, originally known as the University of Arizona, School of Agriculture building, was the first building constructed on the University of Arizona campus in Tucson, Arizona, United States. Old Main is one of the oldest surviving educational structures in the western United States. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

David Brian Stidham was a pediatric ophthalmologist stabbed to death in Catalina Foothills, Arizona as the result of a murder-for-hire plot that stemmed from a colleague's professional jealousy. Bradley Alan Schwartz, also a pediatric ophthalmologist, and Ronald Bruce Bigger, a hit man, were arrested and convicted for the murder.

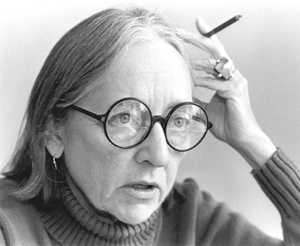

Judith Chafee was an American architect known for her work on residential buildings in Arizona. She was a professor of architecture at the University of Arizona. She was a recipient of the National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship to the American Academy in Rome during the middle of her career and was the first woman from Arizona to be named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

Hirsh's Shoes is a Mid-Century modern store building located in Tucson, Arizona, United States. Designed in 1954 by Jewish-American architect Bernard "Bernie" Friedman for entrepreneur Rose Hirsh, the open plan storefront is an iconic retail standard. Rose C. Hirsh hired Friedman to design this building as a free standing shop in what would become an early strip mall. Though now surrounded by other buildings, it was owned and operated by the Hirsh Family from its construction in 1954 until 2016. The opening of the store was featured in the Arizona Daily Star on April 7, 1954 and for 62 years the Hirsh Family maintained the character-defining architectural features of the north facade and unique architectural expression that defined the mid-century era. In 2014 the Hirsh Family restored the roof mounted neon sign.

The Tucson Inn is a motel located in Tucson, Arizona, in an area now known as the Miracle Mile Historic District. The motel was built in 1953 in the Googie architecture and Modernist style, and is an example of historic 1950s Mid-century modern highway motel architecture.

Tucson Modernism Week is an annual cultural festival and celebration organized by the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation held in October - November which highlights Southern Arizona's unique and distinct mid-20th century architecture and design heritage. Established in 2012 the programming includes tours, lectures, films, publications, and special events. The event draws national and international speakers and participants. Tucson Modernism Week produces an annual magazine featuring original scholarship and content highlighting the contributions of 20th-century designers, architects, and thought leaders. The events and programming primary focus on Tucson and greater Pima County which is home to a significant collection of mid-twentieth century buildings by noted architects including Judith Chafee, Arthur T. Brown, Bernard J. Friedman, William Kirby Lockard, William Wilde, Sylvia Wilde, Taro Akutagawa, Tom Gist, Bob Swaim, Nicholas Sakellar, and others.

John W. Buchanan (1871–1941) was an American politician from Arizona who served in the states first three legislatures, the first two in the House of Representatives, and the third in the State Senate. During his political career he also served as Pima County Treasurer and as Tucson's City Treasurer.

Consuelo Hernandez is an American politician. She is a Democratic member of the Arizona House of Representatives elected to represent District 21 in 2022. She is president of the Sunnyside Unified School District.

The Jacobson House is a residential building located in Tucson, Arizona, designed by the American architect Judith Chafee. The house was commissioned in 1975 by clients Joan and Arthur Jacobson and completed in 1977. The property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2022 and designated a Pima County Historic Landmark in 2022.

The Ramada House is a 3,800 square-foot residence located in the Catalina Foothills area of Tucson, Arizona. Designed by architect Judith Chafee in 1973, and completed in 1975, the house combines modernist-inspired design with traditional O'odham shade structures to create a unique living space that exemplifies the tenets of critical regionalism. The property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2006.

The Arizona Cancer Center Chapel also known as the Soleri Chapel or the "De Bonis Chapel" is a distinctive architectural resource located within the University of Arizona Cancer Center at 1515 North Campbell Avenue in Tucson, Arizona. Designed by the internationally renowned Italian-American architect Paolo Soleri and built in 1986, the chapel reflects Soleri's vision and commitment to blending art, architecture, and nature. The late twentieth-century design is a rare example of Soleri's architectural work in southern Arizona.

References

- ↑ Purvis, Bob, Arizona Daily Star, Old Tucson former exec Blackwell died at 72, October 7, 2003, 14.

- ↑ Hernandez, Margo, Arizona Daily Star, Park Officials Face Dilemma, January 20, 1989, 1.

- ↑ Hernandez, Margo, Arizona Daily Star, Park Officials Face Dilemma, January 20, 1989, 2.

- ↑ Hernandez, Margo, Arizona Daily Star, Parks Board Orders Study, February 16, 1989, 16, 15

- ↑ Bustamante, Mary, Tucson Citizen, ‘Eyesore’ will get reprieve, February 16, 1989, 19.

- ↑ Hernandez, Margo, Arizona Daily Star, Uncompromising architect is shaping dreams, February 19, 1989, 16.

- ↑ Judith Chafee, Arizona Daily Star, Blackwell House fits well within its desert home. April 9, 1989, 35.

- ↑ Patterson, Ann, Arizona Republic, Major Chafee Work in Danger, May 28, 1989, 163

- ↑ Limberis, Chirs, Arizona Daily Star, Blackwell House won't be demolished, July 7, 1989, 17

- ↑ Rawlinson, John, Arizona Daily Star, Pact at last opens way to restoration, December 2, 1991, 17.

- ↑ Limberis, Chris, Arizona Daily Star, Bond Funds for Kolb Road extension – Board, November 14, 1992, 26

- ↑ Limberis, Chris, Arizona Daily Star, Blackwell House is spruced up as part of UA preservation drive, November 23, 1992, 13.

- ↑ Limberis, Chris, Arizona Daily Star, UA students ask for 180-day delay of Blackwell House Demolition, December 12, 1992.

- ↑ Jimmie, Justine R. Tucson Citizen, House given a reprieve from wrecking ball, December 17, 1992, 37.

- ↑ Charbonnier, Alex, Tucson Citizen, Deal could save home, May 10, 1993, 15

- ↑ Katleman, Jenniffer, Tucson Citizen, Grijalva to push for end to Blackwell House, July 31, 1995, 1.

- ↑ Tucson Citizen, Blackwell House: Bring on the bulldozers, please, August 7, 1995, 6.

- 1 2 Morlock, Blake, Tucson Citizen, County Votes to Raze Blackwell House, June 3, 1998, 21.

- ↑ Tucson Citizen, Desert House Demolished, June 29, 1998, 21

- ↑ Martinez, Pila, and Newell, L. Anne, Blackwell House architect Chafee dies, November 10, 1998, 8.

- ↑ Judith Chafee," Arizona Architects Project, University of Arizona Libraries, accessed March 19, 2023.

- ↑ Ramada House," National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, National Park Service, 2022.

- ↑ Gebhard, David, "Judith Chafee," Pritzker Architecture Prize, 2022.

- ↑ "Ramada House," ArchDaily, accessed March 19, 2023.