Early life

Potts was born in or before 1840 [4] near Fort McKenzie, Montana. He was the only child of his Kainai-Cree [5] mother, Namo-pisi (Crooked Back), and Andrew R. Potts, a Scottish fur trader. Upon the death of his father in 1840, Jerry was given to American Fur Company trader Alexander Harvey by Namo-pisi prior to rejoining her tribe. A violent, vindictive man, Harvey neglected and mistreated Potts before deserting him in 1845. American Fur Company trader Andrew Dawson of Fort Benton, Montana, a gentle man who was called "the last king of the Missouri," adopted young Potts. [6] He taught the boy to read and write and allowed him to mix with the Native Americans who visited the trading post to learn their customs and languages.

In his late teens, Potts, who adopted the carefree mannerisms of the frontier, joined his mother’s people and, from then on, drifted between them and Dawson. During this time, Potts passed all the nai-Cree rites of passage including the final agony of the Sun Dance wherein the fledgling brave is tied to a pole by thongs threaded through his chest muscles. Successful completion of this rite meant the youth had achieved glory by tearing himself loose either immediately or by staying tied to the pole in absolute silence for up to three days and then tearing loose. Potts chose to remain the full three days for such was his nature. He also belonged to several of the secret warrior societies which prevailed in large numbers throughout the Blackfoot nation. Still, he wore Euro-American clothing most of the time including a fashionable hat that sported a wide headband.

Adulthood

Potts was employed for several years by the American Fur Company, and from 1869 to 1874 he worked as a hunter for various whiskey traders. He gained fame as a warrior. As a person of mixed blood, he had to prove to both Indigenous peoples and Euro-Americans that he could cope in their respective cultures, and was well served by his quick wits, reckless bravery, skills with the knife and lethal accuracy with both a revolver and a rifle. [7] Potts married two sisters of the Piegan Blackfeet (Aamsskáápipikani) named Panther Woman and Spotted Killer, [8] who blessed him with several sons and a couple of daughters. He named one of his sons "Blue Gun" in commemoration of his favourite rifle. His many descendants still live mainly in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Montana. Three of his descendants, including Janet Potts, became Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers during the middle years of the 20th century.

By the time Potts was 25, he was wealthy due to his horse trading. His herd rarely included less than 100 horses, which made him the second wealthiest First Nations person in the area. Though his horses carried a number of diverse brands, he could always produce bills of sale (even though he could not read them himself) for most of them. Those without papers, if they were American horses, were sold in Canada while paperless Canadian horses were sold south of the Medicine Line. Those branded with the markings of the US Cavalry were sold as far north as possible unless he had papers proving they had been purchased legally. The going rate for a good horse at the time ranged between $75.00 to $150.00 so his large inventory showed his wealth. [9] When he journeyed to Montana Territory to buy horses he would carry cash - often as much as a thousand dollars - with which to make the transactions. People knew he carried such amounts but they also knew he was a good fighter, so he was left alone.

Around this same time, he became a minor chief with the Kainai, in recognition of his bravery in battle, his unquestioned leadership abilities, and his knowledge of the prairies. It is said he knew every trail from Fort Edmonton to the lands of the Cheyenne and Apache and every hill between those trails. He could find game when all others had returned to camp empty-handed. He spent much of his time in what is now Montana, guiding, trading horses, and drinking.

Potts always received more salary than any other guide/interpreter because as a guide he had no equal. He was useful as an interpreter because he spoke all the Indigenous languages of the Prairies. His interpretations would also be different, depending on who he was speaking to. His interpretations of the long, verbose speeches of the Native Americans were always short and concise. Long speeches would be reduced to only a few words. His interpretations of the indigenous languages, however, were always long and passionate. Potts did this because he understood that long speech in Indigenous cultures was meant to show respect, while for English-speakers, it was only a way to show off. [10] Once, following a Blackfoot chief's extremely long, flowery, impassioned speech to a delegation of visiting officials who had arrived from Ottawa to sign a historic treaty with the Blackfoot people, Potts remained silent as if fully digesting the colourful language. Finally, when asked what the chief had said, the laconic Potts shrugged and replied, "He says he's damned glad you're here." On another occasion, when asked by Inspector MacLeod what lay beyond a high rising hill ahead, Potts muttered, "Nuther hill."

He was fluent in American English, Blackfoot, and Crow (Apsáalooke aliláau), had a better than average ability in Plains Cree (nēhiyawēwin) (which he would speak only when necessary), and was passable in Lakota-Sioux (Lakȟótiyapi), Assiniboine (Nakona or A' M̆oqazh), and Algonquin. He also understood the differing cultures of the Indigenous peoples and the North-West Mounted Police. He was able to instruct the police in the proper procedures for receiving a Chief. For all his ability to get along with Euro-Americans, though, Potts was very much Indigenous. He never fully understood the Euro-American reasoning. For instance, he could never understand the reason that Euro-American settlers equipped their houses with chamber pots. "Why," he once asked a Mountie, "would anyone piss in a perfectly good eating bowl when the entire prairie lay before him"?

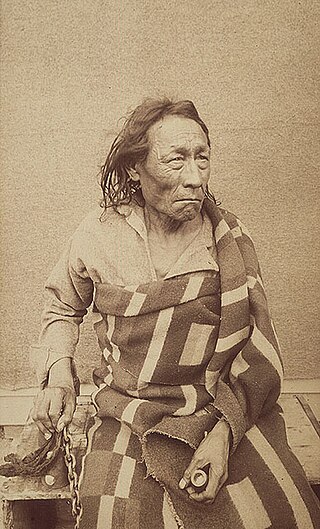

From a distance the stocky, bow-legged Potts looked like a Euro-American trapper in his buckskin clothing, his Stetson at a jaunty angle upon his head. Two .44 pistols hung from his gun belt complementing the Henry rifle which never left his side. On his leg was strapped a long-bladed skinning knife. He always kept a small gun inside a hide-away pocket, a practice that saved his life on several occasions.

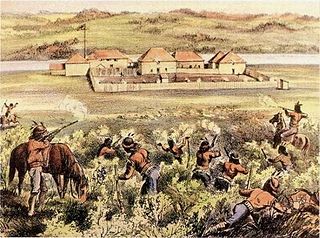

In 1870, various Nehiyaw-Pwat bands of Plains Cree and Plains Assiniboine began a war. They hoped to defeat the Blackfoot weakened by smallpox. An advance party of Cree and Assiniboine, under the lead of Plains Cree Chief Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) and Piapot (Hole in the Sioux), Chief of the Cree-Assiniboines (Young Dogs), had stumbled upon a Peigan camp near Fort Whoop-Up (called by the Blackfoot Akaisakoyi - "Many Dead") and decided to attack instead of informing the main Cree body of their find. Just in the nick of time, Jerry Potts with a group of Peigans and two Blood bands, who were armed with repeating rifles, came to their assistance. In the daylong so-called Battle of the Belly River, on October 25, 1870, near present-day Lethbridge (called by the Blackfoot Assini-etomochi – "where we slaughtered the Cree") the combined Cree-Assiniboine force, who lost over 300 warriors, was defeated. The slaughter was such that Jerry Potts said: "You could fire with your eyes shut and be sure to kill a Cree."

The next winter the hunger compelled the Nehiyaw-Pwat to negotiate with the Blackfoot and, in 1873, Crowfoot (Issapóómahksika - "Crow-big-foot"), Chief of the Siksika (Siksikáwa - ″Blackfoot People″), adopted Poundmaker a man of mixed Cree and Assiniboine parentage, creating a final peace between the Nehiyaw-Pwat (Cree-Assiniboine) and Blackfoot. The Battle of the Belly River was the last major conflict between the Cree and the Blackfoot Confederacy, and the last major battle between First Nations in Western Canada.

In 1871, Potts' mother was murdered by a man drunk on "firewater". So, Potts declared his own personal war on the whisky runners. By the time Potts was 36, he had killed at least 40 men, mostly whisky runners.

In September 1874, Potts was trading horses in Fort Benton, Montana. He was hired as a guide, interpreter and scout by the North-West Mounted Police. His contract as a guide for the North-West Mounted Police was to last twenty-two years. He was paid $90 per month, which was quite a bit higher than a regular guide, and three times a police constable's salary. He ceased working for the force at age 58, because the pain of throat cancer made it so that he could no longer ride, and died a year later, on 14 July 1896, at Fort Macleod. The Macleod Gazette and Alberta Livestock Record paid tribute to the man who “made it possible for a small and utterly insufficient force to occupy and gradually dominate what might so easily, under other circumstances, have been a hostile and difficult country. . . . Had he been other than he was . . . it is not too much to say that the history of the North West would have been vastly different to what it is.” [11]

Jerry Potts is buried at Fort Macleod with the rank of Special Constable in the North-West Mounted Police.

Recognition

The city of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, and the town of Fort Macleod, have boulevards named in Potts' honour.

On 8 September 1992 Canada Post issued a "Jerry Potts, Legendary Plainsman" stamp as part of the Folklore, Legendary Heroes series. [12] The stamps were designed by Ralph Tibbles, based on illustrations by Deborah Drew-Brook and Allan Cormack. The 42¢ stamps are perforated and were printed by Ashton-Potter Limited. [13]

In Sam Peckinpah's 1965 western film, Major Dundee, the character of the scout Samuel Potts, played by James Coburn, was inspired in part by the persona of Jerry Potts himself

A fictional account of his life is featured in the book, The Last Crossing, [14] by Guy Vanderhaeghe.

Jerry Potts Firearms:

The last rusty remains of Jerry Potts Firearms came from the Fort Whoop Up rifle collection.

Many people believe Jerry Potts had a Henry Rifle but the pictures of Jerry with the rifle show it had a side loading port. The Henry Rifle did not have the side loading port. Jerry Pott's rifle was a 1866 Winchester Lever Action YellowBoy. The last remaining 1866 Winchester rifle part (with Jerry Potts name on it) was chambered in .44 Henry (Rimfire).

Jerry Potts also had a Top Break Auto Eject Revolver. It was a Smith & Wesson Double Action Frontier Model chambered in .44-40 Win.

Interestingly, the rifle in the photograph with its prominently raised side plates on the receiver, appears to be an 1873 Winchester. This rifle would also fire the .44-40 cartridge, same as his revolver.