Life

The only source on Chewu's life is the Brief Sketch of the Life of Chan Master Chewu (Chewu chanshi xing lue) by the monk Mulian. [1]

Jixing Chewu was born in Fengrun County, Hebei Province. [1] During his youth, Jixing Chewu extensively studied all the classical texts. [1] At the age of 22, he experienced a profound realization of life's impermanence due to illness. This led him to ordain under Master Rongchi at the Sansheng Hermitage in Fangshan. The following year, he took the full monastic precepts at Xiuyun Temple under the Vinaya master Hengshi. Subsequently, he pursued advanced studies under tropisms prominent Buddhist teachers. They included Master Longyi of Xiangjie Temple, Yogācāra study under Master Huian of Zengshou Temple, and sutra study with Bian Kong of Xin Hua Temple. [3] [4]

In the winter of the 33rd year of Qianlong (1768), Jixing Chewu visited Guangtong Temple to study under Chan Master Cui Ru Chun. He received the mind seal from this Chan master, becoming his Dharma heir. [1] This established him as a 36th-generation lineage holder of the Linji School. In 1773, when Cui Ru Chun relocated to Wanshou Temple, Jixing Chewu succeeded him as abbot of Guangtong Temple, a position he held for 14 years. [1] [2] [5]

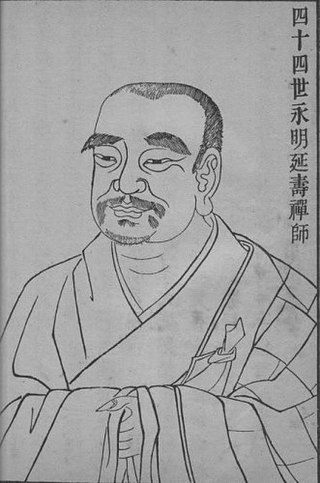

However, Chewu felt that something was missing in his spiritual life. Influenced by the writings of Chan Master Yongming Yanshou who also practiced Pure Land, Chewu was inspired to practice Pure Land Buddhism, writing: "how much more in this age of decline would it be especially right and proper to follow and accept [this path], coming to rest one's mind in the Pure Land?" [1] Chewu later abandoned Chan practice and dedicated himself exclusively to Pure Land practice. [1]

In the 57th year of Qianlong (1792), he became the abbot of Juesheng Temple, serving for eight years. [1] In 1800, Jixing Chewu retired to Zifu Temple (資福寺) on Mount Hongluo (Hebei), intending to live a secluded life. However, his teachings attracted numerous followers, leading him to rebuild the temple as a center for communal Pure Land practice. He became widely revered and earned the title "Hongluo Chewu," with contemporaries praising him as the foremost promoter of the Pure Land tradition in the realm. [6]

Chewu died on the 15th year of Jiaqing (1810).

Jixing Chewu was honored as the twelfth patriarch of the Pure Land School by later figures like Yinguang.

Teaching

Like previous Pure Land authors, Chewu recommends that Pure Land practitioners develop bodhicitta, give rise to faith and vow to say his name to be born in the pure land. [1] He also writes that one should strive to give rise to four mental states and that "if [even] one of these four minds are present, then one's pure karma will be fruitful": [1]

- Shame for all our past evil deeds.

- Joy at having had an opportunity to hear the pure land teaching

- Sorrow at how karmic obstructions are beginningless and at the difficulty of encountering the pure land teaching

- Gratitute for the great compassion of the Buddha

According to Chewu, reciting the Buddha's name with these various mental qualities will make one's practice fruitful. [1] This practice also does away with the need for performing specific rituals like repentance rituals. [1] He argues that this feature of the Pure Land dharma gate is one of its advantages over other more complex methods that require rituals. Thus, Chewu writes that the Pure Land practitioner does not need to confess their past deeds, since "when the mind reaches the point of reciting the Buddha's name just once, one is able to extinguish the faults [accumulated over] 8,000,000,000 kalpas." [1]

Turning to the practice of nianfo (buddha recollection) itself, Chewu mainly describes it through the phrase chi ming (holding the name), which does not indicate oral recitation only, but can also be keeping the name in mind without reciting it. [1] In some places, Chewu clearly means oral recitation, but in others he describes the practice as a mental recollection. He seems to have been open to both oral and mental recollection of the name, not emphasizing any one over the other. [1] According to Jones, what mattered to Chewu was that "the practitioner keep the name in mind at all times, understanding that the presence of the name both realizes and brings about the identity of his or her mind with the Buddha." [1]

For Chewu, the name 'Amitabha' is equal with all the Buddha's virtues. Through holding the name, one awakens to all the Buddha virtues and purifies the mind. As Chewu writes:

The essence of all the gates of teaching is to illuminate the mind; the essence of all the gates of practice is to purify the mind. Now for illuminating the mind, there is nothing to compare with nianfo Recollect the Buddha (yi fo) contemplate the Buddha (nianfo), and you will surely see the Buddha manifesting before you. This is not a provisional skillful means! One attains to the opening of the mind oneself. Is this kind of Buddha contemplation (nianfo) not the essence of illuminating the mind? Again, for purifying the mind, there is also nothing to compare with nianfo. When one thought conforms [to the Buddha], that one thought is Buddha; when thought after thought conforms [to the Buddha], then thought after thought is Buddha. When a clear jewel drops into turbid water, the turbid water cannot but become clear; when the Buddha's name enters into a chaotic mind, that mind cannot help but [be] Buddha. Is this kind of Buddha contemplation not the essence of purifying the mind? [1]

Chewu thus argues that the holding of the name in mind leads the mind to become Buddha without any effort on our part. If one focuses on Amitabha, then the pure land is within one's mind, and one's mind is also in the pure land. As Chewu writes, "they are like two mirrors exchanging light and mutually illuminating each other. This is the mark of horizontally pervading the ten directions. If it firmly exhausts the three periods of time [past, present, future], then the very moment of contemplating the Buddha is the very moment of seeing the Buddha and becoming the Buddha." [1] According to Chewu, this makes Pure Land practice more direct, reliable and easier than Chan practice, which relies on the more subtle and difficult methods of "seeing one's nature". [1]

However, Chewu also held that if one's mind turned away from thoughts of the Buddha, one could regress from one's faithful focus on the pure land and once again become entangled with defilements. As such, the Pure Land practitioner needed to constantly maintain the practice of "holding the name", deepening and extending it throughout their day as much as possible to prevent any possibility of retrogression. [1]

Like some Japanese Pure Land Buddhists, Chewu also promoted the exclusive practice of Pure Land nianfo. He argued that human life was too short and precious to waste it on other Buddhist practices, as they were not as reliable as the nianfo and thus constituted a waste of energy and spirit:

Hold on to the Buddha's name each and every moment! The days and nights must not pass away empty; practice pure karma each and every instant! If one sets aside the Buddha's name and cultivates the holy practices of the three vehicles, this too is squandering one's spirit. Even this is like a common mouse trying to use a 1000 pound crossbow; how much more the activities of those in the six paths of birth and death ! If one puts aside pure karma in favor of the small results of the provisional vehicles, this is also an empty passage of days and nights. Even this would be like using a precious jewel to buy one garment or one meal... [1]

The constant practice of nianfo also helps ensure that at the moment of death one will be focused on Amitabha and his pure land. [1] Regarding the metaphysical foundation of Pure Land thought, Chewu draws on Yogacara mind-only thought to argue that the pure land are also mind, writing that "It is essential to know that the phrase 'a-mi-tuo-fo' has its main import in the doctrine of mind-only." [1] For Chewu, this means that all reality is non-dual with the "true mind", the pure foundation consciousness (alaya) and that all phenomena are interconnected and interfused. [1] While all things retain their individuality on the relative level, they are non-dual with the pure land. This is the foundation for the doctrine of sympathetic resonance, or ganying, which Chewu and many other Pure land authors rely on to explain how nianfo works. [1] Thus, the way nianfo works is that it strengthens the link between the Buddha's mind and the practitioner's mind, making them resonate or vibrate together. As Chewu explains:

Now the reason that Amitabha can be Amitabha is that he deeply realized his self nature as mind-only. However, this Amitabha and his Pure Land, are they not [also the practitioner's own] self-natured Amitabha and a mind-only Pure Land? This mind-nature is exactly the same in both sentient beings and Buddhas; it does not belong more to Buddhas and less to beings. If this mind is Amitabha's, then sentient beings are sentient beings within the mind of Amitabha. If this mind is sentient beings', then Amitabha is Amitabha within the minds of sentient beings. If sentient beings within the mind of Amitabha recollect (nian) the Amitabha within the mind of sentient beings, then how could the Amitabha within the mind of sentient beings fail to respond to the sentient beings within the mind of Amitabha? [1]

In other words, nianfo enhances the symmetrical relationship which already exists between Buddha and practitioner. Even though we do not know it, the Buddha is in our minds and we are within the Buddha's mind. Amitabha is always aware of us, but we are not aware of the Buddha. The practice of Buddha recollection makes one aware of the Buddha, who is already aware of us, and this makes Buddha and being a phenomenon in each others' minds. This is sympathetic resonance (ganying), which is a relationship on the conventional level of phenomena and also a non-dual identity of the level of principle. [1] This account of how nianfo works is Chewu's main original contribution to Pure Land Buddhism. [1]